This is a test

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Significant life passages are marked by ritual in virtually every culture. Weddings and funerals are just two of the most institutionalized yet troubled ones in our own society. A wide variety of rites, both traditional and invented, also mark birth, coming of age, and other major transitions. In Marrying & Burying Ronald Grimes, a founder of the n

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Marrying & Burying by Ronald L. Grimes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Initiating

If we ignore the ritual and magical paraphernalia of New Guinea manhood, how close it all is to the standard anxiety-drenched American conception of masculinity!

—David Gilmore1

All this claiming of superiority and imparting of inferiority belongs to the private school stage of human existence where there are "sides" and it is necessary for one side to beat another side, and of the utmost importance to walk up to a platform and receive from the hands of the headmaster a highly ornamental pot. As people mature, they cease to believe in sides or in headmasters or in highly ornamental pots.

—Virginia Woolf2

1

Cowboy Christianity

Who initiates the North American adolescent male? Who cares enough? Who is wise enough? Who has a tradition sufficiently rich and nuanced? Your grandma? Your parent? Your boss? Your first sexual partner? If no one does, everybody does. If everybody does, no one does.

In most societies manhood is a status to be achieved. Whatever can be won can also be lost—thus the extraordinary fragility of manhood. The white, middle-class, North American version of masculinity is in the throes of a severe crisis even though, or because, men remain in power. The nature and value of our sort of manhood can no longer be taken for granted. There is no good or just reason for construing it as a generic norm for defining the whole of humanity. The critical questioning of our gender by women and nonwhite males leaves us drenched with anxiety. Many who are currendy contemplating the dilemma suspect that the prize of manhood is an empty, though highly ornamental, pot, the competition for which we should outgrow.

Theorists argue that rites of passage thrive in small-scale societies and decay or die in large-scale industrial ones. If their claim is true, I wish it were not. In many of the smaller, more traditional ones initiations transform boys into men. They do so by clearly marking the transition with ceremony. Using protracted seclusion, physical exertion, and grueling ordeals, elders inscribe traditional knowledge in the bodies of initiates, thus ensuring the continuity of generations. This is the purpose of male initiation.

By contrast, coming of age in North America is extraordinarily dittuse—accomplished more by ritualization than by rites. The distinction is important and part of a larger set of terms including ritual, ritualization, ritualizing, and rites. "Ritual" refers to the idea; "rite," to the action designated by it. "Ritual" is general and abstract; "rite" is concrete and particular. Thus, I speak of "a rite," never "a ritual." "Rites" are differentiated from ordinary interaction. They are typically concentrated, focused, and named: Christian baptism, Jewish bar mitzvah, Muslim Ramadan, and so on. Rites are recognized by practitioners and defined by traditions.

Ritualization is less differentiated, more diffuse. The term denotes biological, psychological, or social processes that are not generally recognized as ritual but that can be seen as such. Lovemaking, housekeeping, canoeing, giving birth, footnoting, and TV watching are among the activities that scholars have treated as ritual—"ritualization" in my scheme. Others include the aggressive and mating activities of animals as well as neurotic and psychotic human behavior. Ritualization is largely preconscious or unconscious.

Since there are no culturewide rites of passage in North American society, most men undergo initiation without benefit of rites. Instead, they experience ritualization, usually in unconscious—sometimes in excruciating—ways. They go to war, visit prostitutes, play chicken, and obtain driver's licenses. A few try to invent rites of passage. Such efforts at ritual creativity constitute "ritualizing," the deliberate attempt to incubate ritual activity. The -izing suffix signals ritual processes that are less differentiated than rites but more deliberate than ritualization.

For most of us there was no coming-of-age party, much less a becoming-a-man rite. I came of age years ago. I am still doing it. My initiation, like that of many men, has not been an event but a messy process. Although other men have similar stories, our initiations into manhood were not undergone together, and they have not bonded us into an age cohort or gender group, nor have they allied us with a collective of respected elders. There are some conventional markers of manhood: getting a driver's license, having sexual experiences, leaving home, getting married, securing full-time employment, doing military service, graduating, becoming a father. Any of these, all of these, or none of these may function as transition markers, but these events are not in themselves rites, much less effective ones. Often they are driven by violent, unconscious ritualization

In any particular man's life the conventional markers may not be the real ones. If I were to peruse the list of man-making events looking for the most formative moments of my own male adulthood, I would have to revise it to include leaving home for college, two marriages, one divorce, the death of my parents, the births of three children, and the death of one of them. My initiation does not coincide with a single ceremony, and it bleeds profusely into other ritual processes.

This process whereby one rite piggybacks on, evokes, or bleeds into another I call "ritual entailment." For example, say that a father's social circumstances or psychological constitution make it impossible for him to grieve at his daughter's funeral. A year later he attends the funeral of someone else's child and completes his grief work there. The first rite "entails" the second. Because initiation into manhood continues to be worked out in the context of other rites, we make a serious mistake if we consider one rite of passage in isolation from others. The work of one rite, I believe, often continues in another.

If we search out only the formal instances of initiation, we may miss the heart of the matter. For most North American males initiation is not a moment or an event but a puzzle of shards pieced together as we tell stories about our adolescence. In some cultures young men are ritually initiated by elders who are invested with the social and religious authority to transmit the wisdom of the tradition. In ours sedate middle-aged men invent their initiations by recollecting what they suffered and by inventing what they never quite underwent. We do not lack initiatory experiences or the ritualization of manhood, but we do lack shared, effective initiation rites. The few men who are formally initiated join clubs and fraternities in which a privileged few hold membership. So our few initiation rites divide us. They do not integrate us into a common masculinity, much less a common humanity.

In my mid-thirties I began to write a book of autobiographical fiction. Many of its stories were marked by initiatory motifs. They allowed me to meditate on the ways that the child is the father of the man, to borrow Wordsworth's apt phrase. They enabled me to play with the tangle of motives that characterized my formative years. They were means of negotiating my name, claiming my vocation, and contemplating the meaning of manhood.

Originally, the main character was called Ronnie, a name I gave up as I crossed the Texas state line on my way to college. From then on I was Ron, except on legal documents and scholarly books. 1 would have been Roxie had I been a girl. The decision about my name was made late one night as Mom and Dad (Nadine and Milton) were strolling back to their trailer house. They were on their way from a movie at the Roxy theater in San Diego, where they were working for Consolidated Aircraft during World War II. Since I was born a boy, I was dubbed Ronnie, officially Ronald, in honor of the star of the movie Mom and Dad saw that night. His full name—infamous in the circles I travel and famous in the only remaining superpower there is under heaven and on earth—I stubbornly refuse to put in print here.

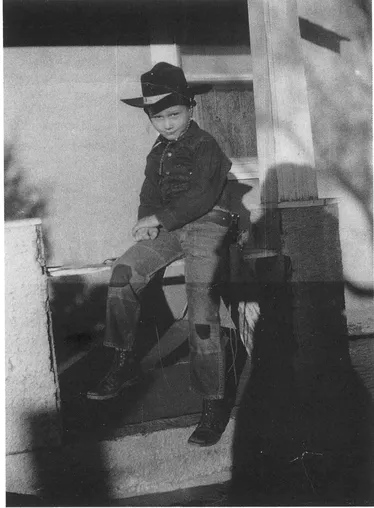

The character soon took on a semi-independent lite, and Ronnie became Harley. Harley, who is between eight and ten years old through most of the stories, began to develop ideas of his own that did not match what actually happened to Ronnie. The name change marked the beginning of the fictionalizing and mythmaking that were necessary for me to understand myself, particularly my religious formation, which was shot through with biblical and Hollywood imagery.

By the end of those never-published stories the reader begins to wonder who the narrator is. Is it the grown-up Harley, telling stories about himself in the third person? Or is it Harley's father, who overidentifies with his son, because the boy and he will soon be separated by a divorce? The narrator sounds omniscient, or at least fatherly, but at crucial points his rhetoric and perspective lapse into that of an eight-year-old. Father and son, in some peculiarly mythological way, seem to give birth to each other.

Harley is not sure what it will mean to become a man, much less a religious animal, and he struggles with the question adults are always putting to him: "What are you going to be when you become a man?"

When Lash LaRue came in the flesh to the Lyceum on Main Street, he wore black. Carrying his whip curled around his shoulder, he walked on to the stage as soon as one of his movies was over. They'd promised he would. To Harley, Lash was not as big as he had seemed on the screen. There he was bigger than life. But that little guy onstage—was that really him? He was short, just about the size of a normal human being, one with short legs. A lady with long white legs held Coke bottles, while Mr. LaRue snapped their caps off with his whip. He had a blacksnake whip. He said so. That was what he called it. Harley strained to see whether it had a head or rattles, but the action was too far away to tell. He was sitting where he usually sat on Saturdays, in an aisle seat halfway down the left side so his mom could find him.

The long-legged woman wore a black bathing suit. She was probably the wife of Lash LaRue, Harley guessed, because she let him pop cigarettes out of her mouth, and because they looked into each other's eyes. But Harley could not recall what movie she was from. Maybe she wasn't his wife after all. He wished Mr. LaRue was his father. No he didn't; he changed his mind. What if he got a whipping from this guy who used a whip to stop fleeing outlaws? Wow! And Harley would have a different mother for every movie, because the black-haired, long-legged one onstage was not the only woman Harley had seen Mr. LaRue with. Why did Lash LaRue stay the same and his wives change from movie to movie?

Harley was shy. Still, he waved his hand high and even stood up when the performers asked for volunteers. But they chose a girl—of all people—to come onstage. She tried to crack the blacksnake whip but couldn't. Finally, a fourteen year-old boy succeeded. Everybody but Harley cheered. He wished the girl had cracked it, because the boy was a bully who had declared to the world that Harley sucked. Harley had been furious. The accusation made him remember Elmer, a little calf covered with slobber and froth who goosed his mother for milk. The calf's nose was soft and wet, and his eyelashes were long. Harley got mad when people said he had long eyelashes like a girl or big brown eyes like a cow. He did not suck! And he hated being called a suck by some big bully who got to pop the whip. Harley's mom said that as a baby, Harley had bit a lot, so he knew he was capable of more than sucking. He could bite. Hard.

When Mrs. LaRue pointed to Harley, saying, "Young man, come up here," he gulped and stumbled as he climbed over legs longer than his. Eventually, he reached the edge of the stage that jutted out from the movie screen, and LaRue yanked him up onto it. The boy's blood rushed when the man and the lady both laid hands on his shoulders. He wished he could marry them. And whipping wouldn't matter. If they would just be his mom and dad.

LaRue had pulled out a gun, something he never used in his movies. The movie star was talking about his six-gun to the kids, assuring them that he used blanks, that he would never really kill people, and that children should not play with real ones. This one had no real bullets in it. He went on for a long time about safety. Even Harley was getting antsy with the moralizing.

Then Mr. LaRue shocked and confused his young audience by declaring like a ringmaster that he was going to have a shoot-out with this young man. He had chosen Harley, who was instantly filled with stage fright and on the edge of tears at the thought of shoo ting it out with a movie star who was better than a heavenly father who gave out golden crowns.

Harley was a puppet—led here, turned this way, pointed in that direction. The lady thrust a pistol at him, belted a holster around his waist, and strapped the bottom of it around his thigh. She topped him out with a white hat, kid-size, which Harley still has to this very day.

He and Lash LaRue faced each other across the stage. The lady, the fourteen-year-old, and the little girl who couldn't crack the whip stood near the movie star. Envy filled the fourteen-year-old. Trembling and tears filled Harley. His throat clamped shut. His belly was doing somersaults. He didn't want to kill Mr. LaRue, who was a good guy—even if he did dress in black. Who was going to be the bad guy in this shoot-out? Harley wanted the movie star for a dad; he did not want to be a Wanted guy with a price on his head.

But the lady was already counting, slowly making her way to three, at which number the two "men" were supposed to draw. One. Two. Harley's hand, unnoticed by all but the fourteen-year old, was already on its way to the pearl handle of his pistol. Desperately, he wanted to be a man. He labored to yank the pistol free of its holster and to point it in the right direction while looking deep into Lash LaRue's strangely blue eyes. He knew exactly how it was supposed to be done; he had practiced his fast-draw on the goats at home. The stiffness of his holster forced him to glance down as he grabbed the holster with his left hand so he could get the gun out with his right.

"Three."

He drew and fired. Smoke burned his eyes. His ears were ringing. The girls, and even a few boys, screamed. His heart was drumming dents into his chest bones. Lash LaRue lay sprawled on the stage, his hand clutching his stomach. Harley was numbed by the sight. For a second or two the theater fell silent as a tomb. Then Mr. LaRue peeked up at Harley, bounced back to life, strode across the stage, and hugged the boy off his feet and up into the air. Everyone was cheering when his favorite bull-whipping cowboy whispered in Harley's ear, "Thanks, son." He patted the boy on the rear and sent all three kids back to their seats. The lady touched Harley on the head. She smiled in a way that made him, for a second time, want to marry her.

For years...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Beginning

- PART ONE INITIATING

- PART TWO MARRYING

- PART THREE BURYING

- PART FOUR BIRTHING

- PART FIVE PRACTICING

- Ending

- Notes

- About the Book and Author