eBook - ePub

Apley & Solomon's System of Orthopaedics and Trauma

This is a test

- 1,012 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Apley & Solomon's System of Orthopaedics and Trauma

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Now in its Tenth Edition and in continuous publication since 1959, Apley & Solomon's System of Orthopaedics and Trauma is one of the world's leading textbooks of orthopaedic surgery. Relied upon by generations of orthopaedic trainees the book remains true to the teaching principles of the late Alan Apley and his successor Professor Louis Solomon. This new edition is fully revised and updated under the leadership of new editors. It retains the familiar 'Apley' philosophy and structure, and is divided into three major sections: General Orthopaedics, Regional Orthopaedics and Trauma, thus enabling readers to gain the knowledge they need for their lifetime learning.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Apley & Solomon's System of Orthopaedics and Trauma by Ashley Blom, David Warwick, Michael Whitehouse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section 1

General Orthopaedics

1 Diagnosis in orthopaedics

2 Infection

3 Inflammatory rheumatic disorders

4 Crystal deposition disorders

5 Osteoarthritis

6 Osteonecrosis and osteochondritis

7 Metabolic and endocrine bone disorders

8 Genetic disorders, skeletal dysplasias and malformations

9 Tumours

10 Neuromuscular disorders

11 Peripheral nerve disorders

12 Orthopaedic operations

1

Diagnosis in orthopaedics

Orthopaedics is concerned with bones, joints, muscles, tendons and nerves — the skeletal system and all that makes it move. Conditions that affect these structures fall into seven easily remembered pairs:

1 Congenital and developmental abnormalities

2 Infection and inflammation

3 Arthritis and rheumatic disorders

4 Metabolic and endocrine disorders

5 Tumours and lesions that mimic them

6 Neurological disorders and muscle weakness

7 Injury and mechanical derangement

Diagnosis in orthopaedics, as in all of medicine, is the identification of disease. It begins from the very first encounter with the patient and is gradually modified and fine-tuned until we have a picture, not only of a pathological process but also of the functional loss and the disability that goes with it. Understanding evolves from the systematic gathering of information from the history, the physical examination, tissue and organ imaging and special investigations. Systematic, but never mechanical; behind the enquiring mind there should also be what D. H. Lawrence has called ‘the intelligent heart’. It must never be forgotten that the patient has a unique personality, a job and hobbies, a family and a home; all have a bearing upon, and are in turn affected by, the disorder and its treatment.

HISTORY

‘Taking a history’ is a misnomer. The patient tells a story; it is we the listeners who construct a history. The story may be maddeningly disorganized; the history has to be systematic. Carefully and patiently compiled, it can be every bit as informative as examination or laboratory tests.

As we record it, certain key words and phrases will inevitably stand out: injury, pain, stiffness, swelling, deformity, instability, weakness, altered sensibility and loss of function or inability to do certain things that were easily accomplished before.

Each symptom is pursued for more detail: we need to know when it began, whether suddenly or gradually, spontaneously or after some specific event; how it has changed or progressed; what makes it worse; what makes it better.

While listening, we consider whether the story fits some pattern that we recognize, for we are already thinking of a diagnosis. Every piece of information should be thought of as part of a larger picture which gradually unfolds in our understanding. The surgeon-philosopher Wilfred Trotter (1870–1939) put it well: ‘Disease reveals itself in casual parentheses.’

SYMPTOMS

Pain

Pain is the most common symptom in orthopaedics. It is usually described in metaphors that range from inexpressively bland to unbelievably bizarre — descriptions that tell us more about the patient’s state of mind than about the physical disorder. Yet there are clearly differences between the throbbing pain of an abscess and the aching pain of chronic arthritis, between the ‘burning pain’ of neuralgia and the ‘stabbing pain’ of a ruptured tendon.

Severity is even more subjective. High and low pain thresholds undoubtedly exist, but pain is as bad as it feels to the patient, and any system of ‘pain grading’ must take this into account. The main value of estimating severity is in assessing the progress of the disorder or the response to treatment. The commonest method is to invite the patient to mark the severity on an analogue scale of 1–10, with 1 being mild and easily ignored, and 10 being totally unbearable. The problem about this type of grading is that patients who have never experienced very severe pain simply do not know what 8 or 9 or 10 would feel like. The following is suggested as a simpler system:

Grade I (mild) Pain that can easily be ignored

Grade II (moderate) Pain that cannot be ignored, interferes with function and needs attention or treatment from time to time

Grade III (severe) Pain that is present most of the time, demanding constant attention or treatment

Grade IV (excruciating) Totally incapacitating pain

Identifying the site of pain may be equally vague. Yet its precise location is important, and in orthopaedics it is useful to ask the patient to point to — rather than to say — where it hurts. Even then, do not assume that the site of pain is necessarily the site of pathology; ‘referred’ pain and ‘autonomic’ pain can be very deceptive.

Referred pain Pain arising in or near the skin is usually localized accurately. Pain arising in deep structures is more diffuse and is sometimes of unexpected distribution; thus, hip disease may manifest with pain in the knee (so might an obturator hernia). This is not because sensory nerves connect the two sites; it is due to inability of the cerebral cortex to differentiate clearly between sensory messages from separate but embryologically related sites. A common example is ‘sciatica’ — pain at various points in the buttock, thigh and leg, supposedly following the course of the sciatic nerve. Such pain is not necessarily due to pressure on the sciatic nerve or the lumbar nerve roots; it may be ‘referred’ from any one of a number of structures in the lumbar spine, the pelvis and the posterior capsule of the hip joint. See Figure 1.1.

Autonomic pain We are so accustomed to matching pain with some discrete anatomical structure and its known sensory nerve supply that we are apt to dismiss any pain that does not fit the usual pattern as ‘atypical’ or ‘inappropriate’ (i.e. psychologically determined). But pain can also affect the autonomic nerves that accompany the peripheral blood vessels and this is much more vague, more widespread and often associated with vasomotor and trophic changes. It is poorly understood, often doubted, but nonetheless real.

Figure 1.1 Referred pain Common sites of referred pain: (1) from the shoulder; (2) from the hip; from the neck; (4) from the lumbar spine.

Stiffness

Stiffness may be generalized (typically in systemic disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis) or localized to a particular joint. Patients often have difficulty in distinguishing localized stiffness from painful movement; limitation of movement should never be assumed until verified by examination.

Ask when it occurs: regular early morning stiffness of many joints is one of the cardinal symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis, whereas transient stiffness of one or two joints after periods of inactivity is typical of osteoarthritis.

Locking ‘Locking’ is the term applied to the sudden inability to complete a particular movement. It suggests a mechanical block — for example, due to a loose body or a torn meniscus becoming trapped between the articular surfaces of the knee. Unfortunately, patients tend to use the term for any painful limitation of movement; much more reliable is a history of ‘unlocking’, when the offending body slips out of the way.

Swelling

Swelling may be in the soft tissues, the joint or the bone; to the patient they are all the same. It is important to establish whether it followed an injury, whether it appeared rapidly (think of a haematoma or a haemarthrosis) or slowly (due to inflammation, a joint effusion, infection or a tumour), whether it is painful (suggestive of acute inflammation, infection or a tumour), whether it is constant or comes and goes, and whether it is increasing in size.

Deformity

The common deformities are described by patients in terms such as round shoulders, spinal curvature, knock knees, bow legs, pigeon toes and flat feet. Deformity of a single bone or joint is less easily described and the patient may simply declare that the limb is ‘crooked’.

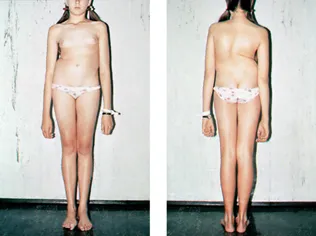

Some ‘deformities’ are merely variations of the normal (e.g. short stature or wide hips); others disappear spontaneously with growth (e.g. flat feet or bandy legs in an infant). However, if the deformity is progressive, or if it affects only one side of the body while the opposite joint or limb is normal, it may be serious (Figure 1.2).

Weakness

Generalized weakness is a feature of all chronic illness, and any prolonged joint dysfunction will inevitably lead to weakness of the associated muscles. However, pure muscular weakness — especially if it is confined to one limb or to a single muscle group — is more specific and suggests some neurological or muscle disorder. Patients sometimes say that the limb is ‘dead’ when it is actually weak, and this can be a source of confusion. Questions should be framed to discover precisely which movements are affected, for this may give important clues, if not to the exact diagnosis at least to the site of the lesion.

Figure 1.2 Deformity This young girl complained of a prominent right hip; the real deformity was scoliosis.

Instability

The patient may complain that the joint ‘gives way’ or ‘jumps out of place’. If this happens repeatedly, it suggests abnormal joint laxity, capsular or ligamentous deficiency, or some type of internal derangement such as a torn meniscus or a loose body in the joint. If there is a history of injury, its precise nature is important.

Change in Sensibility

Tingling or numbness signifies interference with nerve function — pressure from a neighbouring structure (e.g. a prolapsed intervertebral disc), local ischaemia (e.g. nerve entrapment in a fibro-osseous tunnel) or a peripheral neuropathy. It is important to establish its exact distribution; from this we can tell whether the fault lies in a peripheral nerve or in a nerve root. We should also ask wh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Preface to the ninth edition

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations used

- Section 1: General Orthopaedics

- Section 2: Regional Orthopaedics

- Section 3: Trauma

- Index