eBook - ePub

Delta Urbanism: The Netherlands

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Delta Urbanism: The Netherlands

About this book

Delta Urbanism is a major new initiative that explores the growth, development, and management of deltaic cities and regions, with the aim of balancing various goals in a sustainable manner: urbanization, port commerce, industrial development, flood defense, public safety, ecological balance, tourism, and recreation. This book is a detailed history and overview of how one low-lying country has developed the policies, tools, technology, planning, public outreach, and international cooperation needed to save their populated deltas.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Understanding the Dutch Delta

Chapter 1

The Dynamics of the Dutch Delta

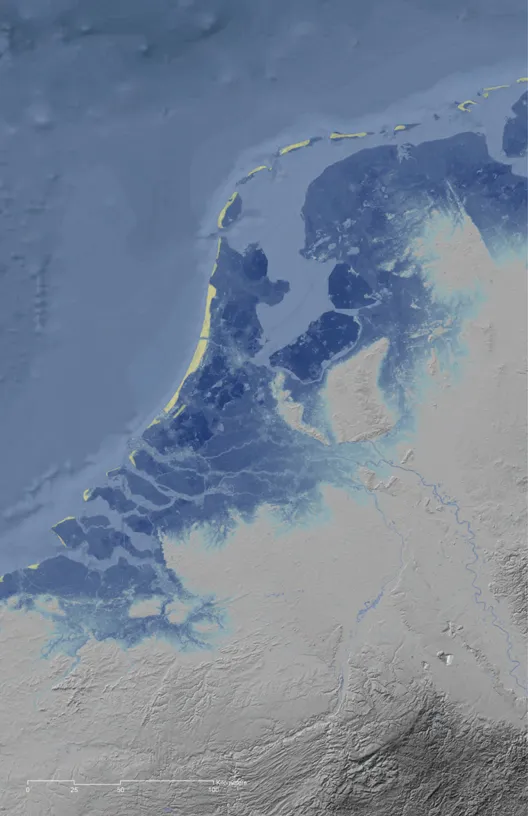

1.1: The Dutch delta.

Map by S. Nijhuis and M. T. Pouderoijen, Delft University of Technology.

“Drown or be Dutch.” It’s a saying that is found in the 17th-century travel diaries of people visiting Holland during its “Golden Age.” It implies that those who lived in the Dutch Delta did not really become its inhabitants until they had learned to control the water. Indeed, water is an important, dynamic element that is the force behind the patterns of sand, clay, and peat that form the natural landscape of the Dutch lowlands.1

Natural processes of sedimentation, erosion, and water stagnation created several lowland landscapes with different substrata and soil. These lowlands can be divided into different geographic regions based on these abiotic factors. Anthropogenic activities also play a role, and this interaction between the abiotic and anthropogenic also produces a standard set of geographic patterns. The divisions employed in this study are based on geological, geomorphological, pedological, and hydrological data that also take into consideration human impact.2

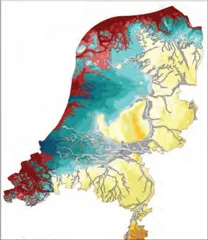

The Dutch lowlands consist of the western and northern peat regions, the northern, western, and southwestern sea clay regions, the dune region, the IJsselmeer (coastal landscapes), the region of the rivers, and the river terrace landscape (see fig. 1.2). These divisions are the point of departure for our discussion of the natural landscape of the Dutch lowlands and the formative power of water.

The Formative Power of Water

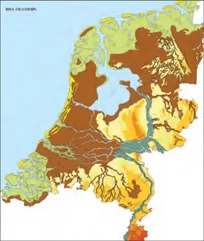

The Dutch Delta’s lowland landscapes were formed by the dynamism of water, the most important force behind the patterns of sand, clay, and peat that make up the natural landscape. These delta lowlands have their origins in the Holocene. Paleogeographic maps of the coastal areas help reconstruct the changes that have taken place since the last glacial period that led to the formation of the natural landscapes in the Dutch lowlands (see figs. 1.3a–d).3

The power of water shaped the lowlands in a variety of ways. The sea, the greatest of reservoirs, was the most dynamic shaper of the Netherlands’ coastal landscape because of its mass. The rise in sea level during the Holocene and the energy of waves, tidal effects, and currents reassembled material from the seafloor and the sediment from the rivers to create the coastal landscape we know today.4

1.2: The physical-geographical landscapes of the Dutch lowlands.

Map by S. Nijhuis, Delft University of Technology.

A second force was the flow of rain and meltwater carried down to the delta from the hinterland by rivers. This produced the river landscape. At the upper extremities of these rivers, many smaller streams come together to erode the land. The middle sections of the rivers are wide, meandering channels that slowly erode the land and transport sediment at roughly equal rates. The lower reaches of the river system are sedimentation areas that flow into the sea without any appreciable change in elevation. Here the rate of sedimentation is usually faster than the rate of erosion. As a result, the river system branches into various changing fluvial belts.5

The third and most subtle force was the standing water of the bog. The seeping, gradual drainage of rainwater set up the conditions for the development of the peat landscape of fens and bogs. Marshes formed in inlets cut off from the sea by sand spits along the coast. The water changed from being saline and nutrient rich (eutrophic) to freshwater and nutrient poor (oligotrophic). This created vertical strata of reed peat, sedge peat, forest peat, and sphagnum peat, which was similar to the horizontal stratification of these materials along the rivers in the peat moors. This process eventually produced an extended, raised peat bog watershed that ran through the entire Dutch lowland.6

The Pleistocene Landscape as a Foundation

During the glacial periods of the Pleistocene, the sea level was at least 100 meters lower than it is today. Large portions of the North Sea region were dry, and England was a part of the European continent. An enormous amount of water was locked up in the great glaciers over Canada and Scandinavia. About 20,000 years ago, the water from the present Meuse, Rhine, and Thames rivers ran southward through the Strait of Dover, where it discharged into a narrow estuary.7

Before the Holocene, the coastline of the North Sea was northwest of Dogger Bank. About 13,000 years ago, the last Weichselian glaciers began to melt, and sea levels rose. In the south, the sea invaded the Strait of Dover through the narrow estuary, and the North Sea basins, which had been dry during the glacial period, filled with water. The coastline eventually rose to the position it occupies today.8

The Netherlands began to sink, although this subsidence was actually a return to earlier ground levels. During the last glacial period, there was a thick sheet of ice over Scandinavia that pressed down on the soil, which forced the ground in surrounding regions, including the Netherlands, to rise. As the glaciers disappeared, Scandinavia rose again and the surrounding land fell—a trend that probably will continue. As a result, the ground level in the Netherlands has fallen several meters while the sea has risen during the last few centuries. But the sea level is not rising everywhere at the same speed. For instance, in the tidal basins, the sea is higher than anywhere else along the coast. These local variations have been the most important driver of the change in the Holocene coastal landscape.9

The Coastal Landscape

Toward the end of the Weichselian era, the vast majority of the Pleistocene landscape not covered by a layer of ice was tilted slightly and had ridges of sand and loess. Particularly in the north and west, the morphology of the land determined which direction the Holocene sea transgression penetrated the coastal plain. In the northern coastal region, between Texel and the Eems River, four tidal basins formed. From west to east, these were the Boorne basin, the Hunze basin, the Fivel basin, and the Eems-Dollard basin. With the exception of the Eems, there were no large rivers discharging into these tidal basins. The IJssel-Vecht basin was located near what is now the coast of North Holland. In the Pleistocene substratum, there were large and deep valleys called the Overijsselse Vecht and the Oer-IJssel, where the IJsselmeer polders and central North Holland are now. To the south of this, in the substratum of Utrecht and South Holland, lay the Rhine–Meuse delta, the Pleistocene river valley of the Rhine and Meuse rivers. The Scheldt basin was located where today’s Zeeland and South Holland Islands now sit.10

a. Elevation of the Pleistocene deposits

b. The Netherlands around 2750 BCE

c. The Netherlands around 50 CE

d. The Netherlands around 800 CE

1.3: Palaeogeographic stages in the Netherlands (from left to right),

Maps by P. Vos, TNO-NITG.

Durable Pleistocene uplands rose up between these newly formed tidal basins. These uplands disappeared in the second half of the Holocene epoch largely because of coastal erosion. In the Holocene (especially during the Atlantic phase), the tidal basins filled with marine and flu-vial sediments. A new system of ocean currents started to circulate after the inundation of the North Sea basins. As a result, the coastline in the western and northern Netherlands took on more and more of a stream form during the Holocene. The concave western Netherlands coastline indicates the former Pleistocene highlands in front of Texel and the coast of Flanders have still not leveled out entirely (see fig. 1.5).

About 3000 BCE, the rise in sea level slowed considerably to only about 15 centimeters per century, and the sea transgressed as far inland as it would go. The wind shifted the waves and tides that carried in sand from the bottom of the North Sea in the direction of the present coast. This created a long, continuous belt of beach walls along the coast of Flanders, Zeeland, and Holland that closed the tidal basins off from the sea. The shallow lagoons created behind the beach walls were fed by the rivers and became a long chain of freshwater fens and bogs.11

In addition, the closing of the coastline changed sedimentation patterns. From the moment the beach barriers stabilized, a series of parallel beach walls began to form just to their west. These walls lay next to one another along the Dutch coast, separated by

1.4: The formative power of water. Island of Terschelling.

Photo by Joop van Hout, Rijkswaterstaat 2006.

beaches. In the south, the only openings in the coastal walls were at the points where the great rivers flowed into the sea. However, in the northern Netherlands, the coastline remained open. There were wide entrances to the sea between low, offshore islands. There were various reasons for this. The seafloor in the northern Netherlands was steeper than the seafloor off the central and southern coast, which meant that it took more sediment to fill them. Moreover, the prevailing western sea wind transported sand mostly to the western coast.12 Finally, in the northern Netherlands, the rivers carried down less sediment than did the rivers in the west. As a result, the coastal region in the north remained vulnerable to the tides and storm floods until the medieval dikes were built.

1.5: Sources of sediments and pits in the Dutch lowlands Sources of sediments carried from elsewhere 1. waves, cross-transport 2. high Pleistocene (headlands) 3. rivers local source peat

Map by D. J. Beets, TNO-NITG.

Around 1000 CE, the coast and the beach walls began to erode as the coastal profile steepened. More sand became available to form the Young Dunes, which grew to a height of 30 to 50 meters. In the southwest and north, the beach walls disappeared almost entirely; in the central Netherlands, the Young Dunes partially covered the beach walls. This wa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Copyright

- Title

- CONTENTS

- Foreword Delta Urbanism

- Preface Safe and Sustainable Delta Cities

- Introduction How to Deal With the Complexity of the Urbanized Delta

- PART ONE: UNDERSTANDING THE DUTCH DELTA

- PART TWO: REINVENTING THE DUTCH DELTA

- References

- Index

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Delta Urbanism: The Netherlands by Han Meyer, Steffen Nijhuis, Inge Bobbink, Han Meyer,Steffen Nijhuis,Inge Bobbink in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.