Introduction

We used to grow up on the street. We’d play, we’d walk to neighbors with a casserole for the block potluck, we’d ride bikes, play games, hang out, socialize. So would our pets. Drivers knew enough to watch out for us. We all survived and thrived. We want that again.

So let’s design streets for living, not just driving. That’s the basic premise of this book: reconsider America’s public realm—going the next step beyond travel lanes and bike lanes, sidewalks and crosswalks. Let’s rediscover all the benefits that streets can offer communities.

West Capitol Avenue, Sacramento. Project design and photo by MIG, Inc.

Nueva Street, San Antonio. Project design and photo by MIG, Inc.

How did we Get Here?

Dirt, paved, brick, cobblestone, concrete or asphalt, the street as a public right-of-way has served humans for thousands of years. Pedestrians, horses and horse-drawn carts shared the road for centuries, along with the occasional chicken, cow and goat.

The bicycle joined the street in the second decade of the 1800s, with the first bike path in America opening in 1894, running along the Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn. As bicycles became safer and cheaper and more women had access to the personal freedom bicycles provided, the bicycle came to symbolize the New Woman of the late 19th century, especially in Britain and the United States.1 The first U.S. on-street dedicated bike lanes opened in Davis, California, in 1967, which led to similar bike facilities nationwide. Today, bikes outnumber cars worldwide by two to one.2

Lincoln Highway between Gettysburg and Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, 1921. Photo courtesy The Lincoln Highway Digital Image Collection, Transportation History Collection, University of Michigan Library (Special Collections Research Center).

Those new-fangled motorized vehicles first hit the streets in 1886. Initially their numbers grew slowly and, in fact, some thought they would never amount to much: “There will never be a mass market for motor cars—about 1,000 in Europe—because that is the limit on the number of chauffeurs available!”3 That threshold was blown past in 1908 when America fell in love with the Ford Model T, the first car for the masses. The love affair lasted for a hundred years. Cars became a symbol of freedom—freedom to go wherever we want, whenever we want. And our streets have accommodated this.

Sycamore at Russell, 1967. Photo courtesy City of Davis and Bob Sommer.

Construction of a national roadway network—starting with the Lincoln Highway in 1913, the early national highway system in the 1920s and the more comprehensive Interstate Highway System in the 1950s—led to unprecedented growth in private transportation and mobility and greatly contributed to the nation’s economic output. It made the automobile the preferred mode of transportation for most Americans and signaled the end of the railroads as the predominant method of transportation for people. Passenger transportation is now dominated by private passenger vehicles (cars, trucks, vans and motorcycles), which account for 86 percent of passenger-miles traveled.4 The automobile took over the road and overwhelmed other uses of the street. Street designs in the U.S. were based on the turning radius of fire trucks; the main goal was to keep vehicular traffic flowing. Streets became conflict zones between cars, bicyclists and pedestrians.

Where are we?

The typical American car is parked 95 percent of the time.5 Yet our roadways and parking systems are designed to ensure fast travels for the two hours of peak car use a day: getting to work in the morning and getting home in the evening. The results are often overbuilt streets that take tremendous amounts of public space, yet often don’t help people successfully navigate through them. Today the vast amount of land devoted to roads—more than 4 million miles of paved and unpaved roads—is more than the land for either parks or government buildings.6 It’s roughly one-third of all city lands.7

The large amount of land devoted to our roads has not actually provided the desired mobility benefits. The 2010 Annual Urban Mobility Report found that traffic congestion cost the U.S. almost $115 billion in 2009. This cost the average commuter more than $800 and about 34 hours per year.8 And, unfortunately, the decades-long focus on vehicular mobility at the expense of safety and non-motorized users of the streets has resulted in unsafe and unfriendly pedestrian and bicycle environments.

Diagram by Anne Fritzler/San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

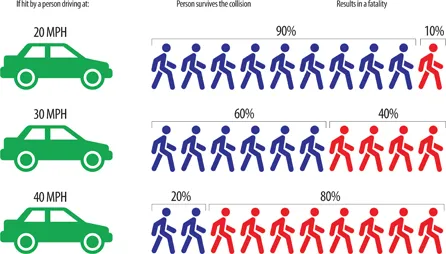

The majority of pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities share a common thread: they occurred along “arterial” roadways that were dangerous by design; streets engineered for speeding traffic often with little or no provision for people on foot, in wheelchairs or on bicycles.9, 10 Between 2010 and 2015 pedestrian deaths increased dramatically. But more cities are now embracing the concept that it is simply not acceptable for so many people to die or be injured on our streets. It has to stop.

Many cities and towns have begun to reverse this trend by better addressing the needs of pedestrians and bicyclists, building on the principles of the Complete Streets and Livable Streets movements. In New York alone, from 2006 to 2010, more than 250 miles of dedicated bicycle lanes were created and several laws to promote cycling were passed.11 More than 700 cities in 50 countries now have bike-share programs; that number is increasing exponentially.

San Francisco Vision Zero Campaign design and photo by MIG, Inc.

Many approaches to travel way design in America, such as multi-way boulevards and corridors with roundabouts, have successfully maintained or increased the roadway capacity for automobiles, while allowing streets to provide safer and more welcoming environments to pedestrians, cyclists and transit users. And jurisdictions are retrofitting sidewalks and crosswalks with ADA-compliant ramps and cross slopes and cues such as truncated domes.

South 11th Avenue, Bozeman, Montana. Photo: Catherine Courtenaye/MIG,Inc.

Streets designed for bicyclists and pedestrians show a clear improvement in overall safety of street users and a dramatic decrease in accidents and injuries. More and more agencies are realizing that retrofitting existing roads to accommodate non-automobile users need not be viewed as a “zero sum game.” Virtually always, better mobility for pedestrians and bicyclists can be added without diminishing the mobility of motorists. And, pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure construction projects also create more jobs than road construction jobs.12 There’s simply no need for warfare between modes of travel.

With the Complete Streets movement, many roadway designs are more sensitive to surrounding land uses and to the needs of bicyclists and pedestrians, supporting walkable and bikeable communities, compact development and mixed land use.13 But the objectives for streets remained the same: move things around. Now, the Complete Streets concepts can be the basis of an even more ambitious transformation of streets to come.

Where are we Going?

We’re going places with different ideas about the cars we’re driving—or not driving. The current Baby Boomer cohort of retirees is the first in which almost everyone has driven; more than 90 percent of Americans aged 60–64 drive. But those older drivers are now driving less. Younger drivers are getting their licenses later and they’re not necessarily traveling in cars they own. People of all ages are making more virtual trips via online buying, telecommuting and social media. And with 77 percent of Millennials living in urban areas (up from 69 percent of Generation Xers when they were that age), they don’t need to drive as much or as far.14

Millennials have entered adulthood with no memory of cheap gas and affordable car insurance. In a 2014 survey, 64 percent of Millennials surveyed said they don’t want a car because it’s too expensive.15 They also have a different ownership model, comfortable with on-demand services and peer-to-peer sharing rather than owning content or devices. Layer on car share, bike-share and ride-share services, and real-time arrivals apps for public transit, and they find little reason to own a car. In the same survey, 81 percent said they use shared services because they have the same advantages of owning a car or bike, without the inconvenience and cost. And their attitudes about public transit are different from Baby Boomers. People aged 16 to 34, with jobs in households with incomes over $70,000—clearly not transit-dependent—increased their public transit use by 100 percent between 2000 and 2009.

That doesn’t mean there won’t be more cars; cars sales usually spike whenever gas prices drop. But, at least in western world urban areas, those cars are just parked more than ever. The International Transport Forum predicts that by 2050—if the developing world follows the historic consumption patterns of richer cities—the total number of cars could triple. Which makes reconsidering streets even more important for them.

Are we there Yet?

The future of transportation—and our streets—is already here. There will likely be fe...