CHAPTER 1 1925–1943 My childhood and life as an evacuee

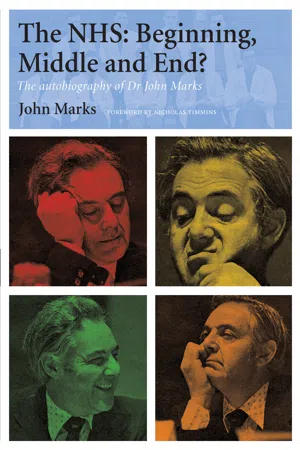

AS A YOUNG CHILD I REMEMBER HAVING THREE GRANDPARENTS, Grandpa and Grandma Goldbaum and Grandpa Marks. My mother’s parents, Julius Goldbaum (probably Judah) and his wife Binya, escaped from Poland around 1880. It was not until years after they were both dead that we discovered his real name was Reznick and that they had used her maiden name because they were petrified that the Russian secret police would find him in England. He was a small, dapper, grey-haired man with a moustache and a neat beard. He spoke English with a thick Polish accent. The ‘parlour’ of their modest house in Shoreditch was covered with certificates testifying to his active support for the local Liberal party. Binya was even smaller than her husband. She always wore a black dress and was completely subjugated by Grandpa.

Grandpa Goldbaum had been a tailor and on a pittance he raised a large family in a reasonably comfortable environment. Jenny, his eldest daughter firmly controlled the other children. Next came three sons – Morris, Leslie and Solomon. Soloman died from rheumatic fever while serving in the Royal Flying Corps. Aunt Esther was older than my mother Rose, but after my mother married she became ‘older’ than her single sister. Rebecca was born in 1900 and changed her name to Irena Gee. The youngest daughter Bertha had a pretty face and shining red hair. At the age of six, dressed in a green satin suit, top hat and cane, I was a pageboy at her wedding to Sam Cohen, who looked rather like Clark Gable.

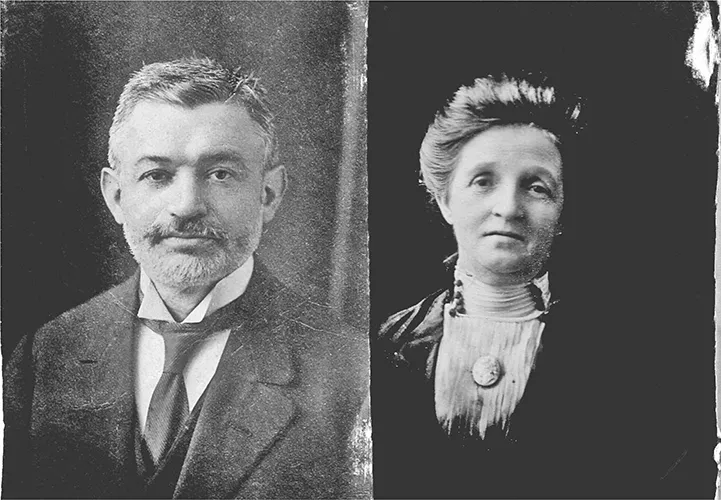

My father’s parents came from Byalistok. Grandfather Marks was a kosher poulterer who always wore the same scruffy cap, ill-fitting black suits, and sported a beard and moustache. His wife Jane (Hanna) died of diabetes in 1924, before my mother met my father. Rebecca (Becky), my father’s only sister, ruled the family. Next in seniority was brother Jack who was never spoken about because he had died in Texas after being shot by a local sheriff in mysterious circumstances.

FIGURE 1.1 My maternal grandparents, Julius and Binya Goldbaum.

My father, Lewis Myer Kitchinsky was born in London on 30 June 1893. His name was changed by deed poll to Lewis Myer Marks in 1923. He told me that his father used his leather belt often and vigorously on his children. As a result of that my father revolted against corporal punishment and only hit me once in my lifetime. He was very good at school and I always felt it was a tragedy that he had to leave school at 14 to work with Becky and his father. They went to country markets and bought chickens, ducks, geese and turkeys, which they took to London and killed in the kosher tradition to sell to kosher butchers. Late in life he told me that his greatest day was when his father bought a donkey to pull the barrow instead of him.

Solly, the youngest surviving child joined the business in due course. He was a car-mad playboy with countless girlfriends. I remember his Alvis sports coupé, which I was allowed to sit in and which I left in gear one day with disastrous consequences when he started the engine without checking. My father was devoted to his brother and sister and often put their interests ahead of my mother’s. This played a large part in the Marks family history, as my father spent a great deal of his time with chickens and not at the pub he owned.

FIGURE 1.2 My father’s father, Mottel Kitchinski.

My mother’s sister Aunt Jenny married an ex-regular soldier called John (Jack) Isaacs. They bought a public house in Islington and one of their customers was the good looking, and relatively wealthy, Lew Marks. Jenny introduced her unmarried sister Rose to this potential husband. Rose worked as a photographer’s assistant – serving customers, developing and printing film, and acting as a fully clothed model. She smoked and could do the Charleston.

After a short courtship they were married on 17 August 1924 at Philpot Street Synagogue, in spite of the hostility of Becky, who refused to share her brothers with anyone. Ironically, she balanced her intense dislike of my mother by doting on me. She was my wealthy aunty from whom I got almost anything I asked. For example, at Broad Street station, the terminus of the North London Railway, there was a model tanker locomotive about 3 feet long. I wanted her to buy it for me. She summoned the station master who said it was not for sale. Neither Becky nor I were pleased. Over the years that memory stayed with me, but as I grew older I began to wonder if it was all a figment of my imagination. My relief was intense when, in my seventh decade, I saw that same model sitting at the Railway Museum in York.

After their wedding Rose and Lew moved to Hackney and he continued to work as a poulterer. This involved early rising, to catch trains to the markets, and late returns. Following my birth on 30 May 1925, my mother found that lifestyle unacceptable. When I was ten months old Jack Isaacs and my father went into partnership and bought a public house, the Grand Junction Arms in Acton Lane, Harlesden. Although they were good friends, their attitudes to work, money and gambling were completely incompatible. Finally my father bought Jack out.

In our garden we had chickens, geese, ducks, rabbits and a goat, as well as an Alsatian dog and a Fox Terrier. Our garden was popular with my cousins and the local kids, but not my mother. Its east side was separated by a wall and some allotments from Waxlow Road, where McVitie and Price had their bakery – one of a very few factories that were functioning at the height of the slump. Sitting on our garden wall I could watch the workers, predominately women, going to and returning from work. In particular I remember a one-legged man busking the workers and singing the popular song, Wagon wheels.1 It was a pitiful sight.

FIGURE 1.3 With my parents, Margate 1929.

The depression was at its height, but we were relatively wealthy. The first school I attended was the state school in Lower Place. My mother made a habit of inviting my school friends, poorly dressed and inadequately shod, for tea. It was probably their best meal in a week.

My parents decided that Lower Place was not suitable and I was sent to Roundwood College, a dame school run by a Miss Templar. Frank, my father’s cellarman drove me to school most days, or sometimes my nanny took me on the bus and we walked the last bit.

There was a small Jewish community in Harlesden. Father and a few others founded the West Willesden Synagogue in a hut in Stonebridge Park. One of the other founders was Henry Filer, who had a jeweller’s shop in High Street. He and his wife Rose at that time had one child, Roy, who was six months younger than me. We became lifelong friends at Roundwood College.

My brother Vincent was born at home on 10 June 1930. He became my mother’s favourite and remained so for the rest of her life. He had knock-knees and a ‘children’s specialist’ recommended that he be fitted with full-length splints, which the poor child wore for about five years. Vincent had a foul temper and I was frequently at the receiving end of it, but because he was ‘crippled’ retaliation was forbidden. Years later it was recognised that if left alone knock-knees straighten up themselves. My sister Sheila was also born at home on 20 May 1934. As a treat I had been sent to stay with Aunty Becky for a while and when I returned home I found this girl, a sister that I did not want and would not accept. More on that later.

At the age of eleven I sat the entrance examination for grammar school – those who did not pass were sent to the local central school. I passed, and in the autumn of 1936 I started at Willesden County School, one of the excellent coeducational Middlesex County grammar schools. Even at that age I had the ability to remember maps and diagrams and my first geography teacher, ‘Pop’ Newton, encouraged me and I was top in geography examinations throughout my entire school life. I did reasonably well all round that year, but in my second year things went very wrong. My geography teacher was Mr Small, nicknamed ‘Piggy’ because he looked and acted like one. I absolutely refused to do his set homework and then nearly every other teacher’s homework.2 When I came top of the geography examination list he accused me of cheating. I did not need to.

My father’s pub was in a tough, hard-drinking, working class area. He knew that his staff pocketed some of the pub’s takings. What was left over was more than enough to make the business a very lucrative one. Most men would have ignored the problem, but my father became obsessed with it. He decided to sell the business and retire at the age of 51, rather than live comfortably without actually working. He became extremely depressed as soon as he stopped work and attempted to buy other pubs, but he never completed the transactions and lost numerous deposits, money in legal fees and other expenses along the way. He picked at his scalp until it bled and his robust figure wasted away. Life for my mother and the three of us became an absolute nightmare.

We moved to a tiny flat in Harlesden near to my school. My father bought another pub in South Norwood and Vincent and Sheila were sent away to boarding school, while I stayed with the family of a school friend, Maurice Jay. That did not work out for me, and so for the best part of a term I commuted daily from Norwood via tram, the Bakerloo tube, and a long walk from Willesden Junction station. At that time no one considered that was a dangerous or unusual thing for a 12-year-old boy to do on his own.

My father sold the pub in Norwood and bought the Seven Sisters Hotel in South Tottenham. Almost miraculously his mental state returned to normal, as did his physical strength. The business was a ‘better class’ and my parents formed friendships with many local business people. However, I had a problem. I had been so idle and difficult at school that I was due for a most terrible report and I would certainly have been demoted to a slower stream. Fortunately, Willesden County School posted reports to parents and mine, sent on my directions to a non-existent address in Tottenham, never arrived. However, when my mother took me to Tottenham County School to enrol the excellent headmaster, Dr Thomas – nicknamed ‘Bert’ after the well-known cartoonist in the Evening Standard – wanted to discuss my school record. Somehow I managed to convince him that I was capable of doing School Certificate in four years and I was put into an appropriate class. My form mistress, Mary Taylor, was a new young teacher who taught my strongest and favourite subject. Life became worthwhile again, but throughout my school life I went to great lengths to avoid doing homework.

In 1938 I reached the age of 13 and I had my bar mitzvah. We were members of the small South Tottenham Synagogue but my paternal grandfather was a member of the prestigious Duke’s Place Synagogue in the City, the equivalent in the United Synagogue to Canterbury Cathedral. As the few orthodox members of the family would not have been able to attend a synagogue outside of central London because their religion forbade them from travelling on the Sabbath, arrangements were made for me to have my bar mitzvah at Duke’s Place.

The bar mitzvah is a great ordeal for a 13-year-old child. He is expected to read from a scroll a portion of the Torah written in Hebrew. In reality, the child has to learn the thing by heart. In addition he has to sing Hebrew blessings – both before and after the reading – and he then has to sing the appropriate lesson from the Prophets with even more blessings. I had a reasonably good soprano voice and made no mistakes, so everyone was happy. I was presented with a book on Jewish festivals which I still have.3

On the Sunday following the ceremony I had my bar mitzvah party in the large function room at the Seven Sisters Hotel. Neither my siblings nor any other children were present. Thank goodness things have changed since then and the normal bar mitzvah party now includes a considerable number of the celebrant’s friends – of both sexes – who have a great time dancing and singing while elderly grandparents look on in amazement.

During 1939 we saw air raid shelters being dug in parks and peoples’ gardens. We were issued with gas masks and leaflets explaining how to make our houses safer. It was decided that young children should be evacuated from the large cities if war broke out and when a German invasion of Poland seemed imminent the plans were activated. On Friday 1 September 1939, along with most of the children at Tottenham County School, I was marched to Seven Sisters Station to board a train. The general rule was that elder children were responsible for their younger siblings. To my lasting shame I refused to take my five-year-old sister Sheila with me. I was prepared to have Vincent, but he refused to come with me, and acting bravely as the elder brother he went with Sheila.

We discovered that our train was going to March, in Cambridgeshire. I was the only person on the train who had heard of it because it had a poultry market and I had been there with my father. Only a British Government could send children to a town that was a strategic railway centre with a huge marshalling yard, Whitemore (now a prison) built by the same engineers that had built the one at Hamm, Germany.

We arrived at March to find they were expecting small children from an infants school. We were lined up and marched through the town; billeting officers allocated us houses along the way. I was in one of the last groups to be settled, and I was billeted with a railway porter’s family. On Sunday 3 September we gathered in Market Square to hear Neville Chamberlain’s declaration of war speech. It was a scorching hot day and at that time the River Nene, which flowed through the town, was an open sewer. The stench was unbelievable.

Many books have been written about the lives of evacuees and their hosts. I was not treated badly, but many others were. Some evacuees took to bed-wetting and other destructive behaviour. In general, the people of March – particularly the children – loathed and resented ‘them Tottenhams’. Once again, I was lucky. Due to my family’s poultry business I knew a local chicken merchant, Sid Harwin, and his very large family. They included Sylvia, who was my age, beautiful, and my first serious girlfriend.

March had a boys’ grammar school, which dated back to Tudor times, and a girls’ high school, Tottenham County, was co-educational, which caused a few problems. In an attempt to give both the locals and the evacuees some form of education, the locals went to school in the mornings and we evacuees attended during the afternoons. To keep us occupied in the mornings we enjoyed free viewings at the local cinemas. March had two cinemas and they changed programmers on Mondays and Thursdays. We saw a lot of films.

A few weeks after arriving in March I decided to run away and go home so that if my parents were killed I would be killed too and not be left an orphan. On the way I called in at the Northern Polytechnic in Holloway Road and enrolled in its matric course. I went home and greeted my parents with these facts. My father reacted most sensibly and without anger. He took me back to March and to Bert Thomas. Bert smiled benevolently, a rare occurrence indeed, and said, ‘Boy how would you like to come to school here and go home every night? We will arrange a half fare season ticket for you.’ Brilliant. Dad brought the ticket and my commuting started.

I go...