This is a test

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

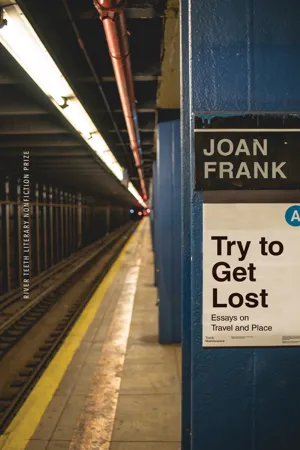

About This Book

Through the author's travels in Europe and the United States, Try to Get Lost explores the quest for place that compels and defines us: the things we carry, how politics infuse geography, media's depictions of an idea of home, the ancient and modern reverberations of the word "hotel, " and the ceaseless discovery generated by encounters with self and others on familiar and foreign ground. Frank posits that in fact time itself may be our ultimate, inhabited place—the "vastest real estate we know, " with a "stunningly short" lease.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Prize by Joan Frank in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Essays. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Cave of the Iron Door

“What I wanted to say . . . was: I could not bear it, but out of my mouth came the words, ‘I cannot bear it.’”

—WILLIAM MAXWELL, SO LONG, SEE YOU TOMORROW

The surface couldn’t have looked simpler. A brief getaway, some extra warmth at a chilly time of year. On the face of it, so natural. A visit to your old hometown—your first hometown, pays natal, place of birth, original setting for those big-bang memories. People smiled and nodded when you told them. Wholesome as a Fourth of July picnic. Yet I remember my heart squeezing as the plane touched asphalt, white sun deceptively mild through the air-conditioned cabin’s window. Out that window: purple-brown desert hills, landscape of childhood. Was it January?

My husband sits beside me on the plane, happily crunching down my ignored mini-bag of mini-pretzels, tapping it to dislodge last bits, his mind dancing (as it does when he sets out anywhere) with images of turquoise swimming pools, tequila cocktails, gritty Mexican food, eye-watering barbecue. He loves heat because he grew up with wrenching cold, so he becomes lavishly cheerful when we’re entering a guaranteed-to-bake kingdom. The plane’s windows are a pulse of light, like the blur filling Kier Dullea’s travel pod in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Have I secretly assumed things will stay as I remember them? Maybe everyone who visits her childhood setting, after a lifetime away, has no choice. You have only your own lonely memory to go by. No one else is still alive—no one you know of—to second you, to say yes, it was that. What can anyone be sure of, after all? Less and less looks the way it once did.

But tell me—what stays the same in the American West for fifty years? For five?

Sky Harbor Airport: the words still send a shiver. Once the very sound of that name punched us little kids in the chest like the word Christmas. Now the image shrinks to that of an old hand-tinted postcard: its single control tower a lone lighthouse, scanning empty expanses of runway in clear, hot sun, its crown a big cut jewel, impenetrable dark glass facets flashing. What dwelt inside? Looming and silent—yes—as the omniscient monolith in 2001. Takeoffs and landings could in fact have been space launches, as much as their drama dazzled my family.

You went to the airport for thrills: on ultraspecial nights to dinner at Sky Harbor’s restaurant, watching planes come and go while you ate. We may as well have been driving our olive drab ’49 Ford straight into the future on those evenings: baby sister Andrea and I bouncing along in the back seat (beltless then), dreaming out the windows, singing made-up songs while dust billowed behind the car—so many roads still unpaved. Mesmerized, our family was, pulled as if programmed toward a new modernity: fat propeller planes servicing ant-sized human masters, a shoal of shining silver Airbuses trundling slowly in and out, plump with passengers. Tiny figurine faces smiled through the capsule windows. Tiny figurine hands waved.

Everyone dressed for air travel as if for church, or a dinner party. Men wore fedoras, jackets, ties—sometimes bolo ties. Plenty of cowboy hats, often with business suits for a formal effect. Women wore crisp shirtwaist dresses, or what was heedlessly called a squaw dress: full-skirted, rickrack-and-sequin-trimmed. Petticoats, hose, heels, girdles—gloves and chic hats. Air travel was still viewed as a privilege; Arizona air itself, ultraclear and dry, prescribed for sufferers of tuberculosis and joint problems. In that clean light, colors shone true, deep and saturated as stained glass, and the clustered planes threw light back in blinding silver.

From behind a simple chain link fence, easily stepped around—the extent of security—we watched passengers descend like royals, stepping across the tarmac toward us with a kind of self-conscious self-possession. There’s something surreal about this (though a child does not yet use that word), about seeing your uncle or grandma step calmly from an enormous silver container—brought through the sky from far away—to approach you here on the Arizona tarmac, mere hours later, smiling.

How toylike those components, I think now. How toylike our assumptions.

How toylike most of the creations of men, including rocket ships. Yet in their very thingness—their density, their irreducibility—how brave. How earnestly they’d been fashioned to do their jobs.

For children, these astonishing creations—trains, boats, cars, planes—were monuments to magic. Every part—the rolling staircase, the little rounded cabin door, its deep interior walls cut as if through thick cake like the door into Winnie the Pooh’s treehouse—magic. The fat gleaming planes pregnant with miniature people, gentle, tamed creatures doing men’s bidding—a giant’s pet, a giant’s playthings. Through a wall of glass in Sky Harbor’s restaurant we could watch the silver creatures lift off and touch down. A pianist played jazz on a white baby grand, stationed atop a central stage. If it was your birthday he played the birthday song while other diners sang along, and the waiters planted a live sparkler on the slice of cake placed before you.

Sparklers.

This isn’t the time to look for the restaurant, though.

It’s time to locate the rental car station, your husband trailing you, people and luggage pushing past. A normal airport’s bustle: white lights, linoleum, loudspeaker noise. But something not normal is also happening. The air feels charged; your body is tensed, half expecting to catch sight of one or more faces from your past floating forward—whirling back to tap you on the shoulder. Excuse me, aren’t you—?

Something’s begun to pump through your limbs and chest: pulse bearing down. Your body, old animal that it is, recognizes first surfaces, first smells, turning agog toward the dusty lavender mountains (color of an old scar), pebbled flatlands, waxy mesquite, soft yellow Palos Verde petals, red cardinals singing their uncannily sweet song, scent of creosote (like pungent wet metal after it rains). Soon you’ll greet favorite cacti: stubby barrel, dignified saguaro, delicate ocotillo, bumpy cholla, prickly pear like needled paddles. Your body has quickened, trembles, alert to this host of living cues. The very air, the purple-brown mountains, their formations, their names: Camelback. Superstition. Praying Monk. Street signs, highways, landmarks: MacDowell. Cave Creek. Indian School Road. Thomas Road. Oak Creek Canyon. The calm desert air. All stand serene, just as they were in your first encounter with them—first map, byways, systems of human community—therefore of meaning—that you ever laid eyes upon, ever took for instruction. Here was the original world. Here was how it had worked.

The floating cosmos, debris still circling in formation. Your big bang.

Time has begun to weave and undulate, to shimmer. It will keep doing this, though you’ll give no sign you’re falling down a wormhole; no hint that your mind and heart are atomizing, recoagulating, melting and twisting into lava lamp shapes, ballooning open, sucking closed, careening, looping—a murmuration of cells, roused from long sleep.

Outwardly, you’re just another aging woman.

Whereas the rental car clerks, my God, are so young.

They could be your grandsons. This your first time in Phoenix? one asks. Here on business? Any good plans? Stuff they’re taught to say. Where are these children from? Don’t they know they are standing on your home? That you were born in St. Joseph’s Hospital and that your dad, a tall handsome wavy-haired Brooklyn native fresh out of Columbia, took the job teaching at Phoenix College and soon helped found Phoenix’s Unitarian Church, designed in a then-bold, modernist style, stationed firmly opposite Barry Goldwater’s regal house in the empty desert, giving shelter to left-leaning and liberal thinkers in the aridity of that hyperprovincial, hyperconservative culture? That your dad also worked as a proofreader for the Arizona Republic; that he was hugely charismatic and charming; also hugely promiscuous and maddened by longing for something he could not name that was apparently forever missing? That your mom in her bottomless loneliness during gaping stretches of empty days without him took you and your little sister to hotel pools like the Westward Ho Hotel and the Ramada Inn; bought you curlicue-topped frostees at the Dairy Queen, and when your dad was actually home that you sometimes all went out to eat in restaurants with dark lighting and glittering glass and silver and tinkling ice like Los Olivos, and like Macayo’s with its brilliantly colored parrot logo exotic and mysterious (a franchise now), and where your father drank and drank except you didn’t know then how much or that there was such a thing as too much; you only made a face at the weirdly ruining bitterness when you tasted his whiskey and Coke or rum and Coke; sweetness of cola so heavenly why would anyone on purpose pour in the gasoline taste? That during other days your mom took you and your baby sis to eat at the Carnation Dairy restaurant where you two little girls sang the Davy Crockett theme together in the women’s restroom because the acoustics there were so terrific? That your mom also took you both to eat at Bob’s Big Boy where just seeing the towering statue out front, the smiling bulge-bellied boy in checked overalls holding aloft his plated, giant cheeseburger, made you crazy-starved for a cheeseburger and chocolate shake and also for dill pickle slices because when you ate at Bob’s (bathed in its blessed air conditioning) you were always given your mom’s pickle slices, which if you held them to the light were translucent? That because her days were chasms bigger than the Grand Canyon fillable only by driving her little girls everywhere, she drove you both so many times to fairyland Encanto Park (could any word be lovelier than Encanto?) and you could always tell by the sudden appearance of green grass alongside the highway that Encanto was near and your hearts would start to pound—where you fed the ducks and ran screaming from stretched-neck geese and ate pink, tauntingly sweet cotton candy that melted so fast on your teeth and you paddled the paddle boat on murky algae-smelling lake water and rode the jewel-bright merry-go-round again and again while it played Claire de Lune, the most beautiful song in the history of forever, while from your cresting horses you shouted here I am momma here here hi momma, waving every time your horse passed her and she stood aside smiling tightly behind sunglasses, arms folded in her wool plaid oversized Pendleton shirt, as if always cold? That she also carted you both to the Phoenix Public Library, which resembled a big white-and-pink sheet cake, where again bathed in blissful air conditioning you and your sister ran straight to your favorite sections and checked out piles of books you could hardly carry, especially the biography series of famous women with black silhouettes of their subjects stenciled on the covers like Clara Barton, Florence Nightingale, Louisa May Alcott, Helen Keller?

Couldn’t the rental car guys just osmose all that?

Couldn’t they sense that you yourself, as a girl, actually somehow managed to be invited to appear on The Wallace and Ladmo Show, the local weekday afternoon television kids’ show which you and your sister and all the kids in the whole state completely and lovesickly adored the way you also adored Shock Theater, which showed hokey old horror films on Saturday mornings hosted by a gruesomely made-up young man called Freddie the Ghoul?

Could they even understand what appearing on Wallace and Ladmo meant?

You only say to these child-men: I was born here.

You stifle the urge to add, hundreds of years ago.

The lads smile blankly as they process paperwork. It must be nice to be so new as to have no thoughts, no tendrils of association, no marks yet left by the world. The car is found. You and your (jolly, unwitting) husband slam yourselves inside it and you, almost panting at the wheel with the intensity of the cosmic onslaught—rippling, pixilated, as if you had swallowed a tab of acid—turn on the air conditioning and creep the car out of the parking lot into a silver-gray afternoon, onto highway surrounded by desert—your desert—which itself, thank the stars, seems not to have changed one bit.

Floaty is how it feels, driving the landscape of earliest memory: set free inside an ancient dream. The desert around you was the first world, the safest world (for a while), the best and only world—best because only. Everything that came afterward, between it and you, seems flimsy—a distraction or occlusion, like swamp fog—all the lives, all the identities grabbed at like slippery buoys since you left this place, age eleven, for California after your mother died of grief, or of what the coroner called an excess of barbiturates in her tiny body, but what you sensed without words through your eleven-year-old bones was a kind of giving up.

It is possible, mused Berna, a friend of your mother and father, that your mother only wanted some sleep.

You, your stunned father, your baby sister, and your dog (in her little carrier) will fly to Sacramento, where your father has already begun a new teaching job.

Confused friends arrive at the Sunnyslope house, blanched with shock, to drink and smoke with your father and listen to him ramble insensibly during your last days there. They ask your father why he is bothering to pack along Ruthie, the gentle, sweet, chestnut-red dachshund you and your little sister so dearly love.

They’ve lost their mother, your father declares. They’ll have their dog.

Your husband reads directions while you drive. (These are the days before cell phones and navigation systems.) Your heart is a nervous rabbit. You glance around—late morning outside clear and parched, already hot, sun glinting off chrome and highway. You’re still expecting any second to spot friends from childhood or—siphoning directly from memory—their parents. Or friends of your own dead parents, other founding Unitarians: the Grigsbys, the Michauds, your dad’s drinking buddy Dee Filson, his kids, his petite black-haired wife Dottie, on whom he was complicatedly cheating and ultimately divorcing—Dee who nicknamed your wild-ass, tomboy little sister “Vyshinsky,” perhaps because the Moscow prosecutor’s first name was “Andrei.” The dentist Doc Purdyman, his pretty wife Martha. Oscar and Berna Rauch. Gone, gone, gone. Yet you expect to see them, all these familiars, trudging ahead beside your lane on the highway like B-movie zombies, whirling to face you just as your car nears them—to lift a wan hand, flag you down.

Many of your own peers are dead.

You turn up the car’s air conditioning.

Something strange has begun, with the writing of this. I am sinking.

The words become a bog, a pudding. I can’t urge thoughts forward but only return to pore again and again over initial lines, combing and re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prologue | The Where of It

- Shake Me Up, Judy

- Cake-Frosting Country

- Cake-Frosting Coda | The Astonishment Index

- In Case of Firenze

- A Bag of One’s Own

- Cave of the Iron Door

- Red State, Blue State | A Short, Biased Lament

- Today I Will Fly

- Little Traffic Light Men

- Place as Answer | HGTV

- Rules for the Well-Intended

- Think of England

- Location Sluts

- The Room Where It Happens

- Lundi Matin

- Coda | I See a Long Journey

- Acknowledgments