eBook - ePub

Aid and Power - Vol 1

The World Bank and Policy Based Lending

This is a test

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

When the major aid organizations made flows of aid conditional on changes in policy, they prompted an extensive debate in development circles. Aid and Power has made one of the most significant and influential contributions to that debate. This edition has been revised to take account of changes within the World Bank itself and the extension of policy based lending to the formerly socialist economies of east and central Europe.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Aid and Power - Vol 1 by Jane Harrigan,Paul Mosley,John Toye in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Background

1

World Development and International Finance Since 1970

1.1 Introduction

Aid and power is our theme. We are interested in assessing the power which international organisations dispensing concessional development finance can exert over the domestic decisions of developing countries. Developing countries, like countries generally, are jealous of their political sovereignty. In practical terms this means that they wish their governments to exercise full independent control over all major policy decisions, unless that control is willingly and voluntarily delegated to others. They do not wish to lose the independence which they have gained relatively recently, sometimes after having to resort to an armed struggle against colonising powers. In the immediate aftermath of decolonisation, most leaders of newly independent nations saw intuitively that political independence could be consolidated only if they could preserve substantial control over the economic forces that can be used to subvert it - the trading companies operating from ex-colonising countries, foreign investors whose priorities care little for national development aspirations, and the domestic economic interests whose resources and ambitions were strengthened by their close foreign connections. The notion of economic independence as the final guarantor of political independence gained ground. Many developing countries adopted a set of regulations governing trade, industrial investment and money and credit whose broad thrust reflected their perceived vulnerability as both political ex-colonies and economic late developers. Weakness, both real and perceived, was the origin of the wide spread in the developing world of the policies of economic nationalism.

In the 1980s, the economic weakness of many (but not all) developing countries has been vividly demonstrated by events. At the same time, the economic policies of nationalism have come under growing challenge. As we shall see, there are some analysts who connect these two in a single theory of cause and effect. Economic nationalism had led to incorrect economic policy, they say, and this had caused the poor economic performance. It was therefore both predictable and right that bad policies should be challenged at a time when economic outcomes were disappointing. This is not a perspective which the present authors share. We do not believe that economic nationalism is necessarily irrational; nor that policy errors were the major source of developing countries' economic distress; nor that it is always obvious that policies focused on liberalisation and widening the scope for the operation of market forces are sufficient to improve economic performance - or that, in some circumstances, they will not make it worse.

But, increasingly, conventional wisdom has come to deprecate such doubts. International organisations like the World Bank — which is the major focus for this study — came to see liberalisation and the release of market forces as the key to unlocking the future development prospects of the developing countries. Further, instead of relying merely on dialogue and the force of rational persuasion to advance the application of these ideas, the Bank, in co-operation with other international organisations (like the International Monetary Fund), decided to make an initially small, but now growing proportion of its new lending to developing countries conditional on their changing their economic policies to those favoured by the Bank and the Fund. The emergence of policy-based lending in the 1980s as a tool for reforming the policies of economic nationalism is the particular subject of this study. We shall discuss not only the adoption and refinement of this form of aid and the reasons why some developing countries have accepted it while others have either not accepted it or not been offered it. We shall also try and examine the factors which influence whether or not the agreed policy changes are in fact made, and perhaps most important of all, whether economic performance has actually improved because of the implementation of agreed policy changes. To the extent that the consequences are good, doubts about the modalities diminish.

But first it is necessary to describe the economic background against which the Bank decided to link its loans with policy reform; and also the intellectual background out of which the Bank's preferred policies for economic development were distilled.

1.2 The International Economic Context

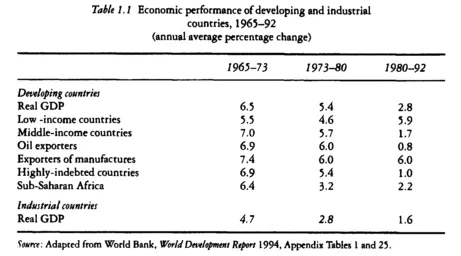

What was the international economic context within which this innovation in aid-giving was developed? Is it plausible to represent domestic policy failures as the major cause of the economic problems of developing countries in the 1980s? To throw some light on these questions, let us begin by looking at some key indicators of developing and industrial country performance over the period 1965-92, set out in Table 1.1.

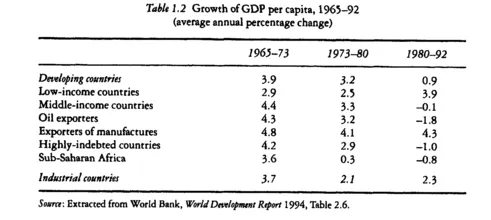

The evidence of growth rate statistics shows that the whole of this period has been one of the gradual deceleration of growth in almost all parts of the world. The only significant exception was in China and the countries of South and South-East Asia in the 1980s. Within this general deceleration of growth, two aspects are worth noting. One is that the developing countries have consistently grown faster than the industrial countries by a margin of nearly 2 percentage points of growth, shrinking to 1.2 as the deceleration proceeded. The other is that within the developing countries, the dispersion of growth rates has widened, with sub-Saharan African economies actually contracting in the early 1980s while China and India were improving on their historic growth performances. The differences in the rates of population growth between countries are included in Table 1.2 to give statistics of real GDP per capita. Once this is done, the picture changes in two ways. The faster growth of real GDP in developing countries is by and large cancelled out by their faster population growth, so that the growth of real income per head no longer differs much between the developing and the industrial world. Apart from that, the effect is to show that real income per head contracted in other parts of the developing world as well as sub-Saharan Africa. Highly-indebted middle income countries and oil-exporters also suffered declines, although not so severely, in the period 1980—92.

The twenty-year-long slow-down of world economic growth is best understood in terms of two critical events. These are the two great oil price rises of 1973 and 1979-80 and the consequent debt crisis which erupted in 1982. They are linked together in a single chain of turbulent events. The governments of the industrial countries allowed an expansion of aggregate demand that provoked a strong bout of inflation in the industrial world in 1972-3, which in turn triggered off a brief boom in non-oil primary commodities in 1972-4.

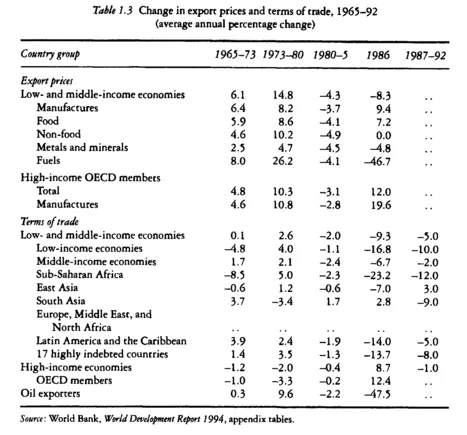

The organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) took advantage of the prevailing shortage psychology to raise the price of petroleum threefold. This shock cut back real growth of output in OECD countries, although inflationary conditions persisted until the end of the decade. A further tripling of the oil price in 1979-80 pushed the OECD economies towards serious recession. At the same time, the arrival of conservatively inclined governments determined to squeeze inflation out of the world system at any cost in terms of unemployment reinforced the already strong recessionary tendencies. Negative, or very slow growth persisted in the industrial countries until the real oil price (which had been eroding slowly because of remaining inflation) finally retreated to a more realistic level in 1986 - see Table 1.3.

On top of all this, a huge debt crisis erupted in 1982, This was a direct consequence of the decision by OECD governments to leave the intermediation of the large OPEC balance of payments surpluses, caused by the oil price rises, to the private banking system. The recycling of these surpluses was believed wrongly to be a profitable (because riskless) form of lending, because the borrowers were mainly Third World governments who would never willingly default on sovereign debt, however the loan money was actually invested. The bankers were right in the sense that no Third World government has formally defaulted on what it borrowed in the 1973—82 period. They were wrong in the sense that few of these loans have been serviced in accordance with their original terms, and so many have had to be written off or very heavily discounted in the banks' portfolios. If the bankers failed to forecast the results of their lending decisions, so did the borrowing governments fail to foresee the results of their borrowing decisions. At the time, it seemed to them that they were getting access to cheap money, vital to bridge growing balance of payments gaps and unlikely to cause them serious repayments problems. Many allowed the money to be spent without much attention to the question of whether the

'investment' would create a surplus, and whether that surplus could be realized as additional foreign exchange for debt service. They, too, were spectacularly wrong.

What brought these mutual miscalculations out into the open at the beginning of 1980 was the course of real interest rates. The years 1979-80 saw the arrival in office in the major industrialised countries of political parties of the right, convinced - or claiming to be convinced - of the simple proposition that inflation can be manipulated by the control of the money supply. In the UK, the USA and the Federal Republic of Germany in quick succession, new administrations arrived with the aim of putting this monetarist doctrine into speedy and effective practice. The reining back of the money supply implied a rise in nominal interest rates, and this certainly occurred, as shown in Table 1.4. But this coincided with the effect of the second 1979 oil price shock which itself was having a powerful effect in undermining demand and economic activity. So the policy-induced monetary contraction came on top of the existing deflationary

Table 1.4 Interest rates, 1965-86

| 1965-73 | 1973-80 | 1980-6 | |

| Nominal interest rate1 | 6.8 | 9.3 | 11.1 |

| Inflation rare2 | 6.1 | 10.l | 1.7 |

| Real interest rare3 | 2.3 | 1.3 | 5.9 |

Notes:

1 Average annual rate.

2 Industrial countries' GDP deflator expressed in dollars.

3 Average 6-month dollar-Eurocurrency rate deflated by the US GDP deflator.

Source: World Bank, World Devlopment Report 1987, Table 2.5 (adapted).

impact of an oil price at $30 a barrel. The inflation rate as well as the growth of real output fell dramatically.

The economic crisis of the 1980s, which was the most serious world economic setback since the Depression of the 1930s, spread through the Third World by a variety of channels. Those Third World countries who had borrowed heavily the recycled petro-dollars had done so at variable interest rates. When nominal interest rates remained low relative to inflation, this borrowing was cheap in real terms; for some periods in the 1970s, real interest rates were negative, so the borrowers were being paid to borrow, rather than having to pay for their borrowing. But the combination of a rising nominal interest rate with a falling rate of inflation (consequent on slower growth plus monetary restriction) created an alarming increase in the real cost of borrowing. It was this, in the deteriorating economic conditions of the early 1980s, that the Third World debtors had to pay contractually, but could not pay in fact.

The reason that they could not pay was that the prices of almost all developing country exports began falling, as indicated in Table 1.3. Under the impact of recession in the industrial countries and a much higher oil price, their terms of trade, which had remained broadly favourable in the 1970s, began a sharp decline. Declining terms of trade combined with higher (and unexpected) financial outflows for debt service constituted sources of acute pressure on developing countries' balances of payments. The widening payments deficits either had to be financed, or their economies had to be adjusted in order to bring demand for foreign exchange into better balance with the decreased supply.

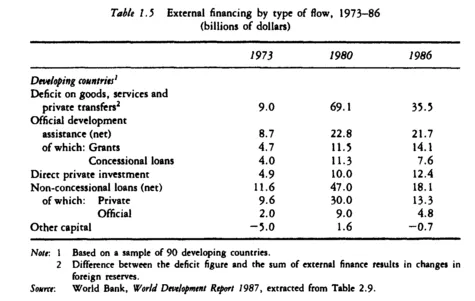

What were the sources of balance of payments finance.? Table 1.5 presents the picture of external financing flows for the period 1973-86. Before the first oil shock in 1973, official development assistance (i.e., foreign aid, both bilateral and from multilateral aid donors like the World Bank) provided the principal means of bridging developing countries' balance of payments deficits. Between 1973 and the early 1980s when the debt crisis broke, the principal source of external finance became private

non-concessional loans, the petro-dollars on-lent by the private commercial banks. Once the debt crisis arrived in 1982, however, this source of funding dried up overnight for all developing countries that were already highly indebted. By 1986, as Table 1.5 shows, it had fallen back to one-third of its 1980 level, with new flows directed to countries like India which had remained creditworthy through the 1970s. But foreign aid was not able to expand to fill the financing gap created by falling levels of new bank lending. The new governments in the lending industrialised countries began cutting foreign aid, as an easy target in the campaign for greater fiscal tightness, so that the expansion of aid from other industrial countries such as Japan and Italy was necessary merely to keep the aggregate flows roughly constant, in the 1980s, then, the global economic context placed a premium on finding ways of bringing down developing countries' payments deficits to the level that could be financed by stagnant aid flows plus rapidly dwindling private commercial lending. In essence, that is what 'structural adjustment' of the developing countries' economies is intended to do.

1.3 The Intellectual Background

The same bout of inflation in the OECD countries in 1972-3 which paved the way for the first oil price shock also sparked off what turned out to be a major reversal of academic perceptions and political attitudes. In the late 1960s, monetarism was still a somewhat esoteric cult among academic economists, although the work of Milton Friedman in the United States was a little better known than was that of his followers like Alan Walters in the UK. The mid-1970s saw a vigorous public debate among economists, economic journalists, political pundits and politicians about the possibilities of macro-economic regulation by means of money supply control. Inflation gradually eclipsed unemployment in the ranking of economic problems, and reliance on variations of monetary manipulation came to be seen as superior to the attempt to fine-tune aggregate demand by fiscal means. The mission of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to the UK in 1976 raised the salience of monetarist approaches to economic policy, and between 1976 and 1980, the need for monetarism became a major campaign plank of conservative oppositions.

Enclosed in the monetary versus fiscal policy debate was the idea that government should not attempt to do too much by way of economic management. The control of the money supply (which had not been seriously attempted as such for forty years) was presented as a simpler and more straightforward policy task than the familiar methods of fiscal demand management. It is not at all clear that this is true, but the assertion indicates the spirit of the times - a weariness with complexities and multiple and conflicting responsibilities for governments. Fiscal demand management was a tricky business, and could be used counter-cyclically, exaggerating booms and slumps instead of smoothing them out. But this was in fact as much to do with the politicians of all parties creating a political business cycle for electoral advantage as it was with the inherent difficulty of such a style of management. However, one important difficulty, long vaguely perceived, was not formalised in economic theory - the problem of countervailing action. Economic agents can and do react to government fiscal stimulation and dampening in ways that neutralise its effects. Keynesian demand management works best with passive economic agents; once they have learned the rules of the game they will play it for all it is worth to them, and its initial effectiveness will be eroded. This was an important point to clarify, even if one finds the assumption of fully rational economic expectations incredible (Killick, 1989: 11).

The breaking up of the consensus around neo-Keynesian macroeconomics in the 1970s spilled over into debates about the validity and utility of development economics. This was, at one level at least, quite odd because logical similarities between macroeconomics and development economics were not very great, the latter having been conceived beyond and outside the conventional neo-Keynesian schema. Nevertheless, such similarities as could be found or invented by ingenious minds, such as those of Harry G. Johnson or Peter Bauer, were duly flourished and criticised. A fetish about physical investment, over-reliance on central planning, and a mistaken analysis of the underemployment of labour and its transfer out of agriculture were some of the 'Keynesian' features of development economics which were identified in order to be condemned. The mood of disenchantment with neo-Keynesianism did not come only from economists of neo-liberal persuasion. It was shared by others, like Dudley Seers, who wanted a more structural, disaggregated analysis in order to tackle problems of maldistribution of income, poverty and inadequate employment. But, in the end, the effect of the discrediting of neo-Keynesian ideas in the development debate was to open the way for the neo-liberals to establish their agenda and their policy preferences. These were eagerly picked up when the political mood decisively shifted to the right at the end of the 1970s.

What then was the neo-liberal agenda and what were its policy preferences? Any attempt to summarise them into one coherent and consistent package is bound to be misleading, and invite cries of 'straw man'. Even with much lengthier presentations than are possible here, such as Toye (1987) or Colclough and Manor (1990), no attempt at definitio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- A note on textual amendments in the second edition

- Introduction to second edition

- Part I Background

- Part II The dynamics of policy reform

- Part III Assessment of effectiveness

- Part IV Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index