- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cinema: Concept & Practice

About this book

In this unique study of the process of filmmaking, director Edward Dmytryk blends abstract film theory and the practical realities of feature film production to provide an artful and elegant analysis of the conceptual foundations of filmmaking and film studies. Dmytryk explores the technical principles underlying the craft of filmmaking and how their use is effective in developing the viewer's involvement in the cinematic narrative.

Originally published in 1988, this reissue of Dmytryk's classic book includes a new critical introduction by Joe McElhaney.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Film & Video1

The The Collective Collective Noun

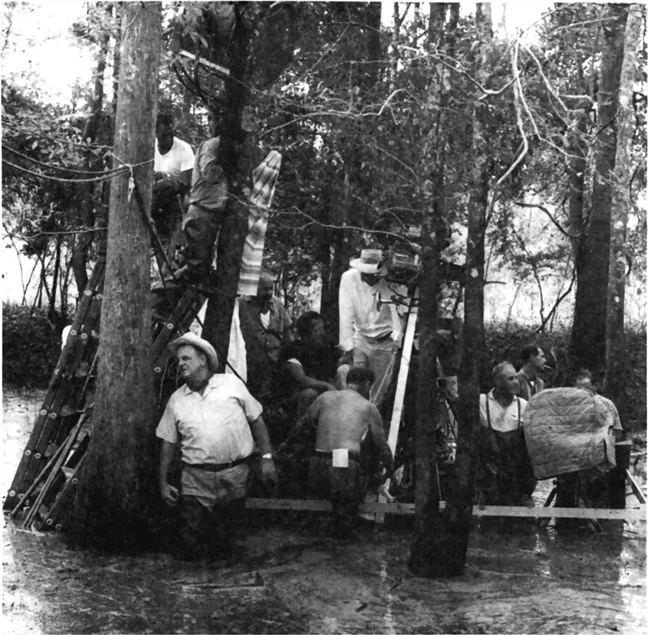

The author and his crew on location for Alvarez Kelly. A successful film is a collaborative effort; sharing the load makes the difficult times easier. Photograph courtesy of Columbia Pictures.

The more I see of the performing arts the more firmly I am convinced that a precise definition of the ideal “Film” would differentiate it from any of its cousins. With the sole exception of film, the performing arts are appropriately named; in all instances the visible artists in this branch of the arts are performers. Whether they stand before an audience or a television camera to deliver one-liners, “read” a fine author’s golden words, dance a noted choreographer’s pas de deux, or sing an operatic aria or one of tin-pan alley’s clever ditties, they are performing. And in these areas a fine performance can be a gratifying experience. The viewer watches, and listens, and usually appreciates the performer more wholeheartedly than he does those who created the material performed.

But in films a “performance,” so recognized, rings falsely* As we have already seen, most definitions of film include the words “life” or “reality.” Regardless of whether the filmic technique stems from Eisenstein or Godard or Hollywood, the actors on the screen must “be” the human beings the viewers watch, human beings who, if the film is skillfully made, soon become familiars, and the viewers’ emotional response should increase along with their involvement with those who live on the screen, whose joys and sorrows they feel as their own, whose existence they pity or envy or dream of sharing. Only after the vicarious experience of being part of such lives begins to dissolve into reality will analysis and appreciation of the film’s separate elements, including the art of the actors and the skills of the technicians who made the film, begin to encroach upon the viewers’ attention. At least, that’s how it should be.

Alas, how often are things the way they ought to be? Ninety-five percent of all film made does not even come close to meeting the standards of an ideal motion picture. But to avoid any possible misunderstanding, let us first exclude all filmmaking which lies outside the scope of this discussion. There are a number of fields that lend themselves to filming; a rather extensive one covers industrial subjects and techniques in their different phases, from explication of manufacturing processes to the selling of the products to agents and dealers. For the consumers of those products and nearly everything else, there are the ubiquitous commercials, without which neither our economy nor our society could now survive. Rock video, designed to sell or display “pop” music, and styled to interest and excite the youthful fans, is a fast-growing newcomer in the television and home VCR fields.

There are the documentaries, which inform the viewer on the states and activities of society and the environment, and docudramas, which do the same thing with less fact and more fiction, and sometimes do it better. There are children’s cartoons, full length narrative cartoons, puppet films, educational films, “art” or experimental films which range through all the genres known to painting, and a few others, such as film vérité, which the more static media cannot accommodate.

Then there is the self-defining “narrative” film, a genre which has sired a large family of overlapping subgenres, but which I will separate roughly and arbitrarily into “theatrical” and “cinematic” films.

Of all the foregoing classifications, excluding only commercials, the public is acquainted primarily with the documentary and the narrative film. Today, the documentary belongs exclusively to television. Although documentarians like Flaherty, Schoedsack, Lorenz, and others have been acknowledged as superior artists whose work attracted sizable audiences, the narrative film unquestionably overshadows documentaries and all the other classifications by a very wide margin. It is primarily this “Film,” whether shot on film, tape, or a combination of both, and shown on a television set or on a theater screen, which will be discussed in the following pages.

Sixty-five years ago, Jacques Feyder, a French film director, wrote, “Everything can be transferred to the screen, everything expressed through the image. It is possible to adapt an engaging and humane film from the tenth chapter of Montesquieu’s UEspiit des Lois, as well as Nietzsche’s Zoroaster.” This somewhat optimistic analysis was written in the days of the “silents,” but now that the screen speaks it is both much easier and much more difficult to realize Feyder’s dream.

It is easier because the marriage of sound and image makes it possible to achieve a certain depth of meaning even when dealing with a difficult concept. When dramatizing a complex human emotion, condition, or conflict, words are often too specialized or ambiguous and the rhetoric too literary for the person of average education and understanding.* And isn’t it this person we should be most concerned to reach?

The versatility of film permits the use of a relatively straightforward verbal language while the accompanying images serve (broadly speaking) to “diagram” the scene’s intellectual or dramatic richness, and to eliminate sources of ambivalence, thus making it accessible to nearly all levels of understanding.

This aspect of film was brought home to me quite dramatically a few years ago at the California Institute of Technology. Following an annual custom, on Alumni Day a number of scientific lectures were presented on campus, all with the aid of specially made films. The combination of nontechnical language and filmed demonstrations clarified some very abstract scientific concepts and activities for audiences that contained many persons with no scientific background whatever. Not exactly new, but a great advance over the magic-lantem slide show.

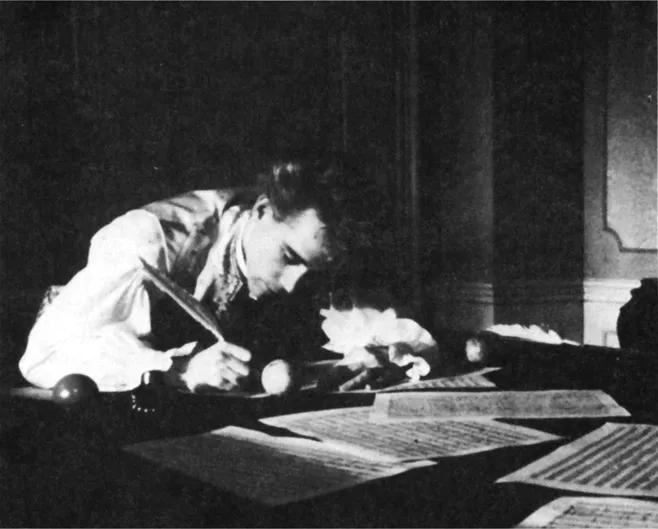

Closer to home, a number of successful narrative films support this point of view. The film Amadeus, beyond its excellent dramatization of character and situation, beyond its presentation of eighteenth century customs, costumes, and behavior, brought the beauty of Mozart’s music and more than a glimpse of some of the technical aspects of his art to millions of viewers, most of them with little knowledge of, or previous interest in, music at this level. The film even impressed a respectable number of those who consider anything beyond punk rock a total waste of time.

The truth is that this happy combination of words, images, and sounds in the interest of deeper content is not often realized, but that is due to the scanty supply of talented filmmakers rather than to the medium’s inability to deliver. As has frequently been pointed out in the world of computers, theorists excepted, a viewer gets no more out of a medium than that medium’s manipulator puts into it.

However, Feyder’s dream has also become more difficult of realization because words have once more largely taken the place of effective imagery. Narrative film has been engaged in a tug-of-war with the theater that the theater, through an almost “Chinese” process of absorption, seems to be winning. Although purists continue to maintain that the cinema should be only a medium for images, most of today’s films are no more than richly illustrated plays. Any argument on this point has been made moot by the reality. And though I will try to make a case for the modified cinematic film as the truest and best art of the screen, only the tunnel-minded will rule out any narrative form which adapts itself to film and succeeds in interesting and entertaining the viewer.

At this point there must be an unambiguous understanding of the word entertainment. The expression is equivocal, but in theatrical terms most people think of it as “something which amuses.” I will always use it in the following senses of the word.

- Entertainment: That which affords interest and amusement.

- To entertain: To engage, keep occupied the attention, thoughts, or time of a person.*

In other words, entertainment is not only Beverly Hills Cop or Star Wars, it is also Amadeus, Ghandi, Missing, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. A film may amuse, inform, explain, analyze, or deliver a message; as long as it holds the viewer’s attention, it is entertaining.

Why all the emphasis on entertainment, or interesting the viewer?

Tom Hulce as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in Amadeus. The actor’s performance is obviously a crucial part of a film, but for the film to be successful, the other parts, including the sound and narrative imagery, must also be excellent Photograph courtesy of Orion Pictures.

Why not, like some purists, consider only the artistic excellence of the film and the skill of the filmmaker? Because without the viewer no film lives—it is merely a long succession of photographs, carrying no meaning and no emotion. Its significance can be brought to life only through the empathetic reactions of a viewer’s involvement. And even the diehard purist must admit that film is a business as well as an art. Building a motion picture requires the services of a large, highly-paid professional crew, the contributions of an exorbitantly-priced group of “artists,” the utilization of tons of expensive equipment, and time.

“Highly-paid,” “exorbitantly-priced,” and “expensive” equals money—a great deal of money. Today, the cost of a very modest film would keep an American family in comfort for a lifetime. The financiers who supply such money, whether through the studios or though individual producers, would like to retrieve their investment along with as much profit as their money would earn while sitting in a bank. The dream, of course, is for a great deal more.

The source of the recouped investment is the viewer. If he does not find the film to his liking there is little recoupment and no profit at all. Such is the fate of many films—in fact, of most films—but for the producing studio, disaster is extremely rare. Ancillary revenues from sources such as video, television, toys, and music albums, all fatten the kitty, and unless it goes as far over the edge as United Artists’ Heaven’s Gate, a studio can “average out.” One hit will make up for a dozen flops, and the losers will at worst furnish a useful tax loss for the parent conglomerate. On the other hand, the independent who gambles it all on one film is challenging one of the world’s highest risk businesses. His chance for making a killing is small indeed. But, fortunately for the good filmmaker, there is never a shortage of gamblers, and the independents, as well as the studios, manage to struggle along, their hopes kept new-penny bright by the few who succeed.

Profit may be the main goal of the producing entity, but most filmmakers dream of creative freedom, and the quickest, perhaps the only way to get it is to make films which attract large audiences. With so much money riding on each production, the director with a record of box-office success is obviously in demand. The greater the success the greater the demand, and the greater the demand the greater the amount of freedom requested, and received, by the film-maker.

A successful motion picture always benefits from a well-known cast. For Broken Lance, this investment paid off—the film won an award for the best Western of 1954. On this lunch break near Nogales, Arizona, the author is surrounded (on his right) by Spencer Tracy and (on his left) by Robert Wagner and Earl Holliman. Across the table are Jean Peters, Richard Widmark, and, with his back to the camera, Hugh O’Brien.

It follows that the filmmaker with a poor success rating soon loses the opportunity to make demands—or films.

Such are the film facts of life. These simple and quite logical parameters pose a number of problems and offer a few opportunities. Many of the films which rack up huge grosses are, to put it politely, tripe. But if the tripe sells, those who produce it get greater freedom to turn out more tripe. The bright side of the picture is that each year a few films, made by thoughtful and talented filmmakers, also manage to attract large film audiences, audiences composed of adults who rarely visit movie houses, and the more responsive members of the youthful community. Together, these two groups can make up an impressive profit-turning array of spectators.

It must be obvious that the filmmaker who can produce a quality film of substance which can also attract and hold the attention of a mass audience must possess abilities far transcending the ordinary. His or her message must be delivered in a manner that is understandable to the average person, yet deep enough to please those who demand nourishment in their entertainment diet; the film must not be pompous, pretentious, pedantic, or overbearing—and it must entertain. It can be as raucous as a Marx Brothers comedy, which the discriminating will easily recognize as a sharp satire of our social and political structures; as brilliant as Doctor Zhivago, which deals with some of the greatest upheavals of revolutionary Russia while holding the viewer’s complete attention with a superior love story; or as stark and stomach-turning as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which lays bare the tragedy and the cruelty of a mental institution while supplying more laughs than most Chevy Chase comedies. Each of these furnishes amusing or emotional entertainment to its viewers while providing substance for those thirsty enough to require it and intelligent enough to demand it. And they all bring our attention back to the filmmaker—which is really a collective noun.

Notes

* It is unfortunate that film’s founding fathers little realized their plaything’s potential, and borrowed their descriptive vocabulary from its antecedents. Because of this we have no adequate word for “being” on the screen, and the word “performance” must of necessity be used in any discussion of the screen actor’s art. Reluctantly, it will be so used in this book.

* See Allan Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987).

* Oxford English Dictionary.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Edward Dmytryk: A Short Biography

- Introduction

- 1 The Collective Noun

- 2 The Indispensible Viewer

- 3 You’d Better Believe It

- 4 The Power of the Set-Up

- 5 Invisibility

- 6 Moving and Molding

- 7 Look at Him, Look at Her

- 8 The Art of Separation

- 9 Rules and Rule Breaking

- 10 The Modification of Reality

- 11 Symbols, Metaphors, and Messages

- 12 Auteurs, Actors, and Metaphors

- 13 Time and Illusion

- 14 The Force of Filmic Reality

- 15 About a Forgotten Art

- Postscript

- Filmography of Edward Dmytryk

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cinema: Concept & Practice by Edward Dmytryk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.