![]()

PART I

The Organization and Administration of Homeland Security

In Part I, the authors examine the basic structure of what has come to now be known as “homeland security” (HS). The concept of protecting our nation is not new, but the term is one that grew out of the devastating attacks on the American homeland, in New York, Washington, DC, and Pennsylvania. As we know, the United States is primarily a nation of immigrants, with a small percentage of our population being true “Native” Americans. But for all of us, naturally born American citizens or naturalized citizens, it is indeed our homeland. In a post-9/11 environment, there have been significant steps taken by all Americans to secure our homeland. The chapters that follow explore just a few of those steps.

Chapter 1: A First Look at the Department of Homeland Security

This chapter is an introduction to the Department of Homeland Security. But this is clearly just a first look. The author will present a very basic explanation of the DHS’s mission and the organizations within the DHS that are charged with our security. We examine homeland security from the “top down,” examining the responsibilities of the federal government and what it does. But many of the other authors will describe different structures, some starting at the bottom with local governments and others that rest with the private enterprise or even the military (state and federal).

Chapter 2: Homeland Security Law and Policy

In the United States, we would like to believe that homeland security is a straightforward mission. However, when it is carried out within a free society, with a complex legal structure designed with checks and balances on government power and protections for individual liberties, it is anything but straightforward. It is vital that those with homeland security or emergency management responsibilities (or both) have an understanding of the governmental and legal parameters in which homeland security policy and emergency operations function. This author presents the reader with an overview of areas of law and policy that impact homeland security in the United States, exploring the meaning of law and policy, sources of legal authority, basics of constitutional law, US agencies and government structures that address homeland security, and examples of major federal statutes, executive orders (EOs), and presidential directives (PDs) impacting homeland security. She also provides brief descriptions of several relevant areas of law, including public health law, laws impacting the detainment of terrorism suspects, and mutual aid agreements.

Chapter 3: Public- and Private-Sector Partnerships in Homeland Security

All too often, the assumption is made that homeland security is a strictly government function. That is not true, however. This chapter begins with a review of several key structural documents, particularly the pertinent Homeland Security Presidential Directives (HSPDs) that relate to the incorporation of the private sector within preparedness, prevention and mitigation, response, and recovery dimensions of emergency management. The author then addresses the role of the private sector as Critical Infrastructure Key Resource (CI/KR) owners and operators to include a review of the governance council structure currently in place within the Department of Homeland Security Infrastructure Protection (DHS IP) Directorate. This direction reflects the manner in which the DHS both interprets and implements the appropriate HSPDs, as well as the private-sector responsibilities as directed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and US Northern Command (NORTHCOM). The chapter concludes with a description of several public-sector and private-sector models being considered by various jurisdictions as well as the salience and effectiveness of these models. Two key models examined by this author are the “top-down” model, which suggests private-sector partnerships need to be constructed and managed by the public sector, and the “bottom-up” model, based on community of practice and community of interest “grassroots” initiatives.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

A First Look at the Department of Homeland Security

KEITH GREGORY LOGAN

They that can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.

–Benjamin Franklin, Historical Review of Pennsylvania (1759)

September 11

September 11, 2001, like many other days of tragedy and infamy, burned into the psyche of every American the mark of terrorism. We will never forget where we were and what we were doing when our homeland came under attack. The consequences of that day have challenged the freedom of all Americans. The loss of lives, the loss of property, and the loss of our security have changed us forever. We all asked how our intelligence and defense agencies failed to protect us. One response was to reorganize the government to ensure that this would not happen again.

Department of Homeland Security

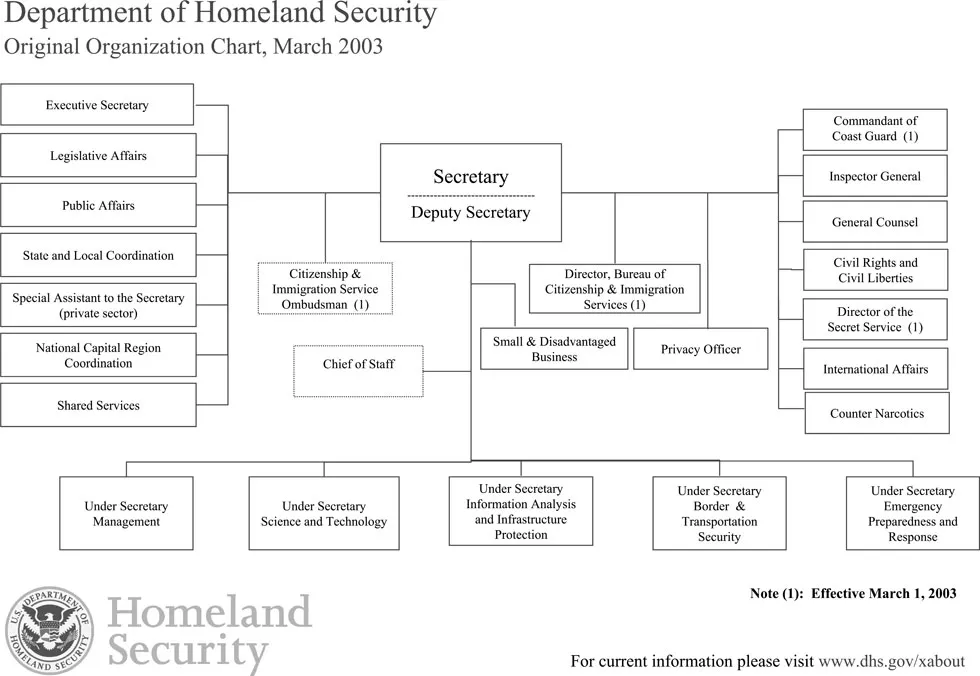

On November 25, 2002, President Bush signed the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (Public Law [PL] 107-296; 116 Stat. 2135), creating the DHS, effective January 24, 2003. The new department was intended to improve government operations and communications, by moving all the essential elements for domestic national security and intelligence under one manager. There have been numerous reorganizations at the DHS since 20031 to improve communications and operations (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2).2

The intent was to include within the DHS all of the federal organizations that had a primary responsibility for homeland security and the sharing of domestic intelligence in order to facilitate communication, policies, strategies, tactics, and control among them. Several agencies were moved under the aegis of the new department, including the US Secret Service (USSS), US Coast Guard (USCG), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Transportation Security Administration (TSA), Federal Protective Service (FPS), and Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC).3 Other organizations or functions were moved, in part, from their parent agencies to the DHS and assigned to various DHS directorates.4 The new DHS Science and Technology Directorate included the CBRN (Chemical-Biological-Radiological-Nuclear) Countermeasures Programs, Environmental Measurements Laboratory, National BW Defense Analysis Center, and Plum Island Animal Disease Center.5 The Nuclear Incident Response Team, Domestic Emergency Support Teams, National Domestic Preparedness Office, and Office for Domestic Preparedness (ODP) were included within FEMA’s new structure.6 The functions of the US Customs Service and the US Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) were transferred into US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), both within the DHS.7 The following other entities were also moved to the DHS: part of the Animal and Plant Inspection Service, Federal Computer Incident Response Center, National Communications System, National Infrastructure Protection Center, and Energy Security and Assurance Program.8

Key DHS Elements

The present DHS organization reflects refinements that have evolved since its initial creation in 2003.9 The USSS, FEMA, USCG, and TSA remain within the DHS and are very similar to their initial organization. Other DHS components have refined their structure, function, and responsibilities. For example, when the FPS was transferred from the General Services Administration to the DHS, it was included as a part of ICE until 2009, and it is now part of the National Protection and Programs Directorate. There have been other refinements within the DHS organization as well. Although not allinclusive, the list below provides a brief look at three distinct segments within the department: the Office of the Secretary (OS), key components and agencies, and advisory panels and committees.

FIGURE 1.1 Department of Homeland Security, original organizational chart, March 2003

FIGURE 1.2 Department of Homeland Security, 2010

The Office of the Secretary

The secretary and his or her staff are responsible for the management and strategic direction of the DHS. In particular, the secretary leverages resources among federal, state, and local governments to ensure that there is an integrated focus on protecting the American people and the homeland.10 Reporting directly to the secretary are the following five functional and administrative areas:

1. Office of the General Counsel (OGC): The OGC is an OS staff office, responsible for providing legal advice and coordinating the activities of approximately seventeen hundred attorneys throughout the DHS and its components. The OGC works closely with the Department of Justice (DOJ) to ensure uniformity among the administration’s legal actions.

2. Office of the Inspector General (OIG): By conducting audits, inspections, and investigations, the OIG is responsible for combating any fraud, waste, and mismanagement that may exist within the DHS or any of its programs, including contracts, grants, and so on. The OIG is considered an independent element of the DHS and makes only recommendations to the secretary for improving the department. The OIG is also responsible for reporting its findings to the US Congress. As with the DHS secretary, the inspector general is appointed by the president of the United States.

3. FLETC: FLETC is where most federal law enforcement officers receive the training necessary to fulfill their agencies’ law enforcement or homeland security missions. The training center of FLETC is based in Glynco, Georgia. FLETC also has a western campus and several satellite centers for specialized training. Special agents, police officers, and security officers receive in-service and refresher training at FLETC’s base or one of its campuses. The two exceptions, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), train in Quantico, Virginia, at the FBI’s National Academy facilities. Many agencies such as the US Border Patrol (USBP) and Secret Service also have their own specialized training schools for agency-specific courses after officers complete their basic training at FLETC. FLETC is also involved in training foreign law enforcement personnel. Since 9/11 FLETC has expanded its homeland security training, along with its basic law enforcement training. In addition, FLETC has broadened into new subject areas, such as counterterrorism, security, intelligence, and law enforcement management. The increased FLETC curriculum is a positive reflection of the growth of homeland security as a discipline.

4. Directorate for Science and Technology: This directorate is the primary research and development segment of the DHS. It provides federal, state, and local agencies with improved technology capabilities that are essential to homeland security.

5. Office of Intelligence and Analysis (OIA): The OIA serves a critical mission that addresses weaknesses in communications and analyses that enabled the events of 9/11. The OIA represents the DHS in the Intelligence Community (IC), as one of the sixteen intelligence agencies under the guidance of the director of national intelligence (DNI). The USCG Intelligence program, another key DHS component, is also part of the IC because of its responsibilities for maritime security and safety. The OIA analyzes information from various sources to assess the threat to homeland security. It is also responsible for communicating the appropriate information to other members of the IC as well as to federal, state, local, and tribal counterparts directly and through Fusion Centers.11

Key DHS Components and Agencies

There are seven independent agencies that are clearly integral to the DHS, each with law enforcement authority. The inclusion of these components played a key role in the creation of the DHS and the centralization of homeland security.

1. US CBP: This is the primary organization that is responsible for border security. The CBP is the largest and most complex DHS organization and has the first-line responsibility of keeping terrorists and their weapons away from the homeland. The CBP has its roots in the USBP, INS, and US Customs Service (USCS). The USCS’s origins date back to the Tariff Act of 1789, when the USCS was the primary source of revenue for our new nation.

2. US Citizenship and Immi...