1

SOCIAL MOVEMENTS AS POLITICS

Charles Tilly and Lesley Wood1

“The ‘March of Millions’ in Cairo marks the spectacular emergence of a new political society in Egypt,” Paul Amar explained in the online ezine Jadaliyya on February 1, 2011. He continues,

(Amar 2011a)

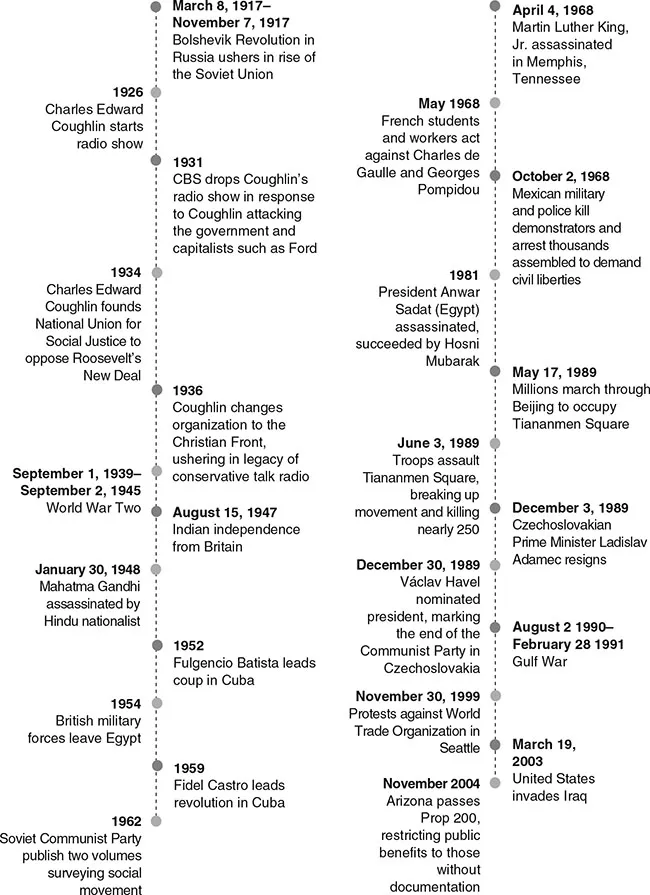

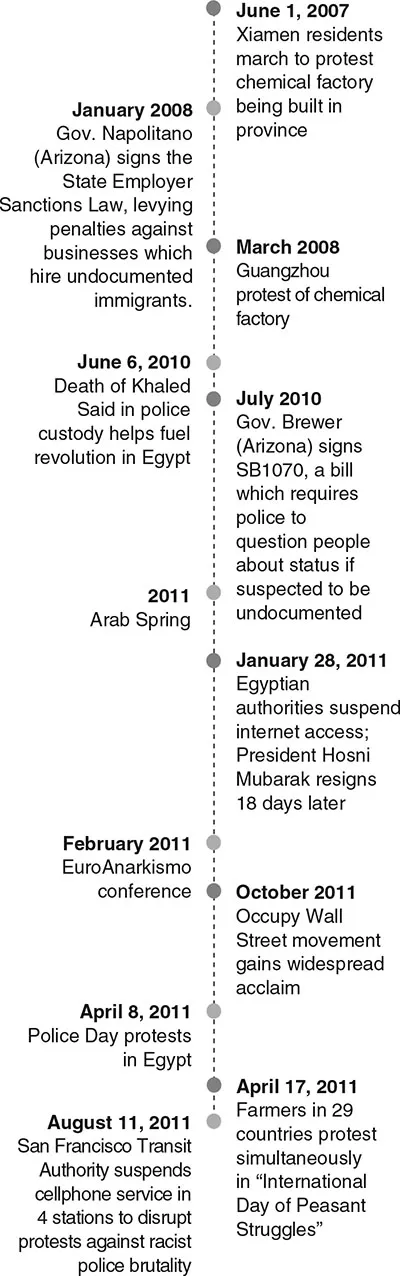

The protests developed within a context of rising frustrations and economic inequality. In recent years, human rights violations and police brutality had created a climate of fear in the country. The wave of protest started with strikes over working conditions and low wages and morphed into marches against police brutality. Groups such as the Kefiya Movement and the April 6 Movement used both flyers and electronic media to mobilize for a large protest on January 25 “Police Day” (a national holiday) as expectations increased following a successful uprising in nearby Tunisia, where another decades-long dictator had suddenly been brought down by popular protests. By the end of January 25, 2011 hundreds of thousands of people were in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and in other cities throughout Egypt demanding the ouster of the longtime president.

The protests were successful in many ways. Former president Hosni Mubarak and his two sons were arrested and interrogated and put on trial. Some political prisoners were released, the dominant political party was abolished, various politicians were fired, the State Security Investigations Service was dismantled, and shop owners who had losses during the curfew were told they would be reimbursed. A referendum was held about the timing of the next election. The fragile relationships among police, military, the wealthy, and Mubarak were destabilized (Amar 2011a).

Six months later, mobilization and frustration were ongoing. Despite attempts by the transitional Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to limit protest through longstanding emergency laws, multiple strikes and sit-ins continued. Sections of the labor movement demanded the renationalization of privatized companies. Activists met in tent cities in the public squares throughout the country to demand the end to military trials for thousands of imprisoned civilians. They also sought justice for families of those killed during the revolution, an increase to the minimum wage, and quick trials for former government officials. Other groups formed and new issues were raised; for example, one thousand women marched in Cairo on International Women’s Day in March 2011 to demand representation in the new constitution. In September, after a rally demanding the end to security laws, about one thousand people marched on the Embassy of Israel, where some entered, destroying documents, and others clashed with security personnel. Salafists, a strain of fundamentalist Sunni Muslims, protested the ongoing detention of affiliated activists, demanded the release of the World Trade Center bomber Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, and protested in support of the prodemocracy movements in Yemen and Syria (Hisham and Halim 2011). Environmentalists protested dependence on fossil fuel (Eriksen 2011), university students demanded the dismissal of university leaders and the election of university deans without any interference from state security (Al Masrya al Youm 2011), and doctors from the Ministry of Health went on strike to demand better working conditions, higher wages, and increased government spending on health care (Carr 2011). Then, tragically, Coptic Christians who rallied and marched against the burning of a church in Southern Egypt were attacked by security forces in early October 2011. Violence spread across the contentious landscape, as frustrations with military rule increased.

Divisions existed between those who highlighted the importance of constitutional reforms and those who prioritized the protection of civil liberties. Some thought that a proposed timeline for reforms was appropriate, while others wanted faster changes. Nonetheless, it was clear that across Egypt, people were willing to meet, march, and rally in order to make the changes they wanted to see.

Neoliberal Designs

As people in Egypt and around the world sought to solve political and economic problems by calling for a social movement, global leaders had a different agenda.

In 2011, the Group of Twenty (G20) Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors proposed to resolve ongoing economic problems by announcing austerity budgets, with cuts to education, health care, public spending, and infrastructure. In response, many people called for a global movement for “real democracy” that would challenge these plans. A motion passed by the EuroAnarkismo conference, which met in London (UK) in February 2011, explained:

(EuroAnarkismo 2011)

Latin America and Asia chimed in as well: in September 2011, Camila Vallejo, a leader in the Chilean student movement, argued that the movement should build a coalition with other sectors unhappy with the regime (Abramovich 2011). In April 2011, speakers at a discussion during Anti-Corruption Week in Bangladesh underscored the need to forge a social movement against corruption to build a poverty-free country (Daily Sun 2011).

The hopeful appeal to social movements also rang out in North America. Along with calls for movements for healthy eating, First Nations sovereignty, and gun control, as well as against the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline, one of the fastest growing social movements in the United States in recent years had been the conservative Tea Party movement. One website defines it as “an American grassroots movement which . . . is advocating reductions in taxes and government spending” (teaparty.org). Its various local manifestations mobilized against publicly funded health care and bank bailouts, and some of its offshoots have been involved in protests against immigrant rights (United Press International [UPI] 2010).

Social Movements

By the twenty-first century, people all over the world recognized the term “social movement” as a clarion call, as a counterweight to oppressive power, as a summons to popular action against a wide range of injustices.

It was not always so. Although popular risings of one kind or another have occurred across the world for thousands of years, what observers described in Egypt were organizations—with leadership, members, and resources—that held meetings and developed a strategy by learning from past movements. In the early twenty-first century, activists built their movement by using Facebook groups and Twitter feeds, adding these to longstanding routines of handing out flyers outside of mosques and in neighborhoods, calling for massive public rallies against police brutality and for democratic reform (Al Jazeera 2011).

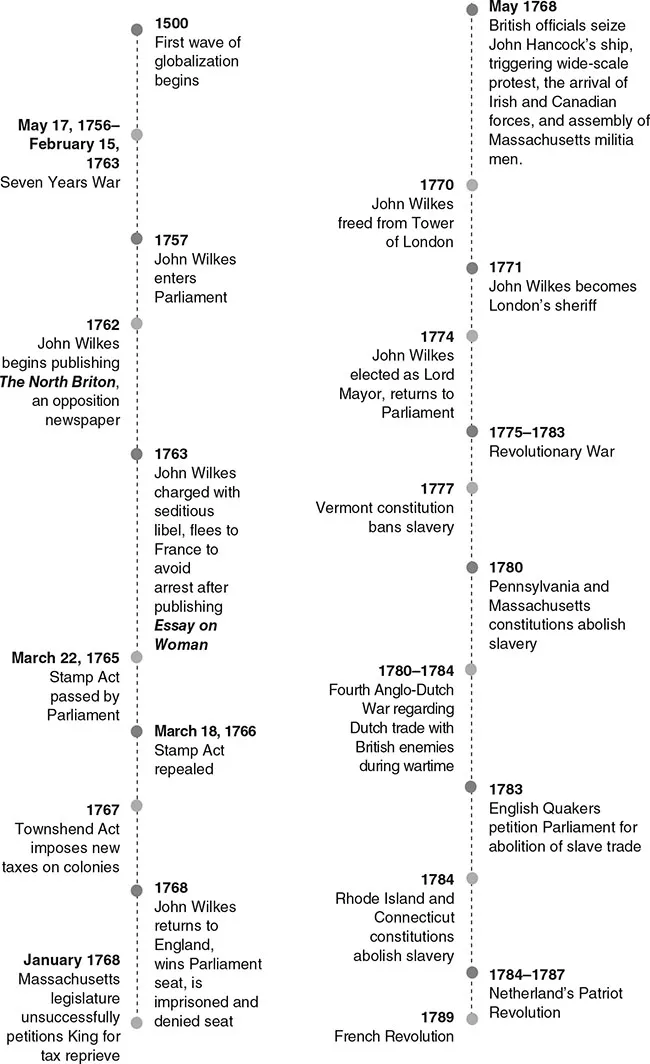

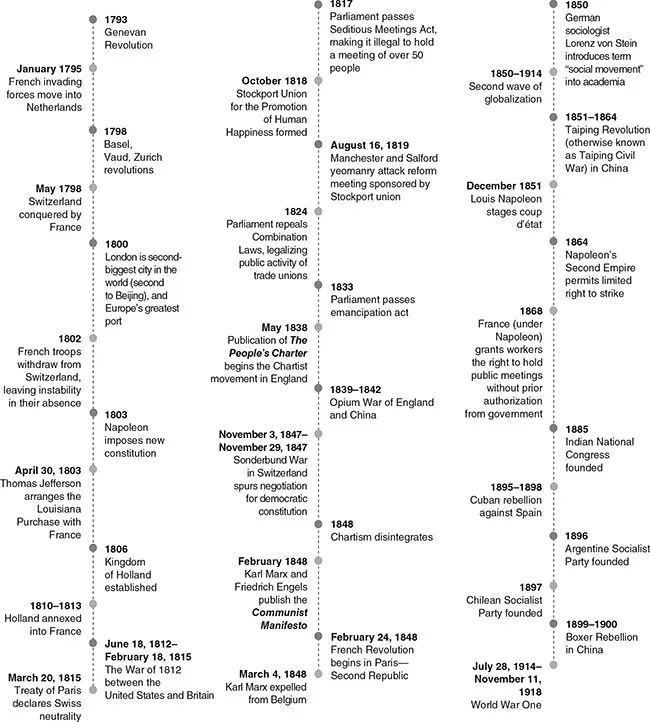

Even without social media, such a form of politics existed nowhere in the world three centuries ago. Popular politics then looked very different. Then, during the later eighteenth century, people in Western Europe and North America began the fateful creation of a new political phenomenon. They began to create social movements. This book traces the history of this invented political form. This book treats social movements as a distinctive form of contentious politics—contentious in the sense that social movements involve collective making of claims that, if realized, would conflict with someone else’s interests; politics in the sense that governments of one sort or another figure somehow in the claim making, whether as claimants, objects of claims, allies of the objects, or monitors of the contention (McAdam, Tarrow, and Tilly 2001; Tilly and Tarrow 2015).

Social Movements 1768–2018 shows that this particular version of contentious politics requires historical understanding. History helps explain why social movements incorporated some crucial features (for example, the disciplined street march) that separated the social movement from other sorts of politics. History also helps identify significant changes in the operation of social movements (for example, the emergence of professional staffs and organizations specializing in the pursuit of social movement programs) and thus alerts us to the possibility of new changes in the future. History helps, finally, because it calls attention to the shifting political conditions that made social movements possible. If social movements begin to disappear, their disappearance will tell us that a major vehicle for ordinary people’s participation in public politics is waning. The rise and fall of social movements mark the expansion and contraction of democratic opportunities.

As it developed in the West after 1750, the social movement emerged from an innovative, consequential synthesis of three elements:

1. social movement campaign: a sustained, organized public effort making collective claims on target authorities;

2. social movement repertoire: combinations from among the following forms of political action: creation of special-purpose associations and coalitions, public meetings, solemn processions, vigils, rallies, demonstrations, petition drives, statements to and in public media, and pamphleteering; and

3. WUNC displays: participants’ concerted public representations of WUNC: worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitment on the part of themselves and/or their constituencies.

Unlike a onetime petition, declaration, or mass meeting, a campaign extends beyond any single event—although social movements often include petitions, declarations, and mass meetings. A campaign always links at least three parties: a group of self-designated claimants, some object(s) of claims, and a public of some kind. The claims may target governmental officials, owners of property, religious functionaries, and others whose actions (or failures to act) significantly affect the welfare of many people. Not the solo actions, but interactions among the claimants, objects, and public, constitute a social movement. A few zealots may commit themselves to the movement night and day, but the bulk of participants move back and forth between public claim making and other activities.

The social movement repertoire overlaps with the repertoires of other political phenomena such as trade union activity and electoral campaigns. During the twentieth century, special-purpose associations and crosscutting coalitions in particular began to do an enormous variety of political work across the world. But the integration of most of these performances into sustained campaigns differentiates social movements from other varieties of politics.

The term “WUNC” sounds odd, but it represents something quite familiar. WUNC displays can take the form of statements, slogans, or labels that imply worthiness, unity, numbers and commitment: Citizens United for Justice, Mothers for Peace, the 99%, and so on. Collective self-representations often act them out in idioms that local audiences will recognize, for example:

• worthiness: sober demeanor; neat clothing; presence of clergy, dignitaries, and mothers with children;

• unity: matching badges, headbands, banners, or costumes; marching in ranks; singing and chanting;

• numbers: headcounts, signatures on petitions, messages from constituents, filling streets, retweets, repostings, and numbers of likes;

• commitment: braving bad weather; visible participation by the old and disabled; resistance to repression; ostentatious sacrifice, subscription, and/or benefaction.

Particular idioms vary enormously from one setting to another. These elements had historical precedents. Well before 1750, Europe’s Protestants had repeatedly mounted sustained public campaigns against Catholic authorities on behalf of the right to practice their “heretical faith.” Europeans engaged in two centuries of civil wars and rebellions in which Protestant/Catholic divisions figured centrally (te Brake 1998). As for the repertoires, versions of special-purpose associations, public meetings, marches, and other forms of political action existed individually long before their combination within social movements. We will soon see how social movement pioneers adapted, extended, and connected these forms of action. Displays of WUNC had long occurred in religious martyrdom, civic sacrifice, and resistance to conquest; only their regularization and their integration with the standard repertoire marked off social movement displa...