- 310 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume, hand-written and contained in three hardbound notebooks, is Wilfred R. Bion's factual record of his war service in France in the Royal Tank Regiment between June 1917 and January 1919, written soon after he went up to The Queen's College, Oxford, after demobilized from the Army.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

DIARY

France,

June 26, 1917, to January 10, 1919

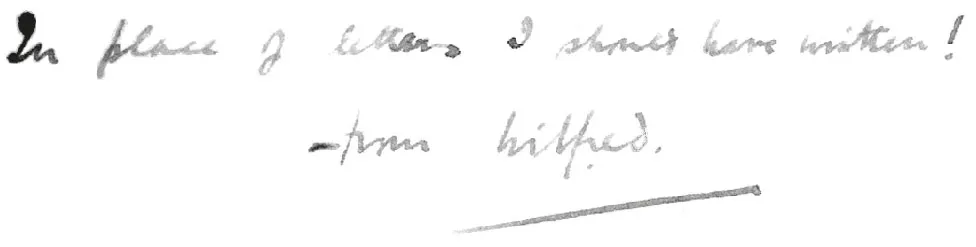

This is Bion’s factual record of his war service in France in the Royal Tank Regiment between June 1917 and January 1919, written soon after he went up to The Queen’s College, Oxford, after demobilization. Hand-written and contained in three hardbound notebooks, it was offered to his parents as compensation for having found it impossible to write letters to them during the war (see ‘Commentary’, p. 199). It has none of the nightmare quality he so vividly depicted in The Long Week-End; he would have been unable to express his very recent painful experiences, especially to his parents. But it is evident that he had them in mind throughout: detailed descriptions of tanks and equipment, explanations of battle strategy, photographs and diagrams were included for their benefit — and ‘bloody’ became ‘b___y’ in deference to their disapproval of swearing, a by no means unusual attitude at that time; Shaw’s ‘Pygmalion’ had been first performed only five years earlier, shocking audiences with Eliza’s ‘not bloody likely’.He writes in the immature style of a public-school boy of that period, using ‘awful’, ‘terrific’, ‘beastly’, ‘absolutely’, ‘frightfully’ and a liberal peppering of ‘verys’. But one must remember that it was his first piece of descriptive writing: he had entered the army at the age of eighteen soon after leaving school; he was catapulted, like millions of others, from schoolboy to combatant soldier in a few months. The horror of that war inflicted on such young men did not contribute to their maturity; it destroyed their youth and made them ‘old’ before their time. Bion’s remarkable physical survival against heavy odds concealed the emotional injury which left scars for many years to come. (It was clear that that war continued to occupy a prominent position in his mind when, during the first occasion we dined together, he spoke movingly of it as if compelled to communicate haunting memories.) The nightmares to which he refers (p. 98) still visited him occasionally throughout his life. He grew old and remembered.1Francesca Bion

1917

In writing this, I cannot be absolutely accurate in some things, as I have lost my diary. In the main it will only be my impressions of the various actions. I do not intend to write much about life outside of action except in so far as it will give an idea of the life we led. My dates of events out of the line cannot be accurate. Actions are, however, accurate as they are very clearly stamped on one’s memory! I don’t intend to write much about the general scheme of action except in so far as it touched on our particular affair. For one thing, you can get that in nearly any report. For another, the general scheme touched one very little, and in the action itself everything is such terrific confusion that you can only tell what is happening in your own immediate neighbourhood. I shall try to give you our feelings at the time I am writing of. Although now one sees how unfounded some of our fears were, yet at the time we could not tell, and it was just the uncertainty that made things difficult to judge and unpleasant to think about.

Our battalion in England was known as ‘E’ Battalion. As a result, all names began with ‘E’. A short time after we got out, the letters were abolished, and we were known as the 5th Tank Battalion.

We had a good deal of training, and I had a very good crew indeed. The crew consisted of the tank commander, a first driver, and, since my tank was a male tank, two 6-pounder gunners, two loaders, and two gearsmen. The gearsmen were also second and third drivers. They were supposed to be able to drive in emergency. Their actual job was to help to steer the tank. The drive of the tank was connected to each track through what were called secondary gears. Thus if you wished to turn to the left, the left gearsman or third driver put his gears in neutral. The officer (who helps to drive) then puts the brake on the left track, and the right track then drives the tank round. When you’ve turned enough, you signal to the left gearsman, who puts the track into gear again. That, and looking after the engine and seeing that nothing is going wrong, is the gearsman’s job. You can see the positions of the crew and the tank equipment generally from the diagram (Figure 1). It is of course a very rough one.

Figure 1

Male tank.

Male tank.

I was in No. 8 Section of 14 Company (afterwards B Company). My first driver was L/Cpl A. E. Allen — a very good man but slightly built and not very strong. My second in command was Sergt. B. O’Toole, an Irishman who was a very good man indeed. He was left gearsman and third driver. He was an orphan and a rather lonely fellow. He was absolutely straight and conscientious and an excellent disciplinarian. He was very popular with the men when they got to know him. I could always rely absolutely that he would do his job. If he had a complaint, he always let me have it. He was an extraordinarily moody fellow in some ways and was not at all popular with the officers at first, as he was very brusque in his manner and his outspokenness was misunderstood. But it did not take people long to realize his absolute worth. He was also Section Sergeant. My second driver and right gearsman was Gunner W. Richardson. He was an old man who had been a frightful invalid before joining, but the army made all the difference to him. On parade he was very nervous and always in trouble for making mistakes. He looked rather like Bairnsfather’s ‘Old Bill’ [Bruce Bairnsfather’s trademark character, in comic drawing sent from France during the war] and was indeed called ‘Bill’, as his name was William! He was a very kind-hearted fellow. Later, in France, when I knew him better, he showed me photos of his ‘missus’ and the kids. He explained he was once a pawnbroker’s assistant and went into lurid details of the trade! He said he’d never go back to the old life after the open air of the army. My left gunner was Gnr. Allen. He was a Portsmouth chap and an absolute boy. He was absolutely street-bred really and rather a grouser. He had very little self-respect, and he always seemed rather a weak spot. With him was Gnr. Hayler. He was a small farmer in civilian life and the reverse of Allen. He was very independent in spirit but always did his work conscientiously and well. At first he used to talk a lot about ‘bad officers’ and so on, and I was more than doubtful of him and wondered how he would turn out. My right gunner was P. M. V. Colombe. He was a very cheerful and good fellow. He had gone to quite a good school; he was a clever man at his work, and one could always rely on him. He formed a sort of common-sense element in the crew. With him was L/Cpl Forman. He was a fellow whom I disliked. He did not do his work really well and always had a terrific opinion of himself. He did an enormous amount of talking. He was, however, absolutely trustworthy.

The other officers in the section were 2nd Lieuts. Despard, Broome and Owen. Broome was a foolish and rather hearty kid. Owen was a good fellow, and so was Despard. Despard was a cheery Irishman — absolutely outspoken and very popular with officers and men. The section commander was Capt. Bagshaw, a very easy-going and hopelessly slack fellow who had been with the original tanks. He was good-hearted but weak-minded and incompetent and got in the wrong set. Cohen was in another section when we left, and Quainton was in No. 7 Section with him. Sergt. Reid, a Scotch fellow, was the second sergeant in No. 8 Section and in Despard’s crew. He was a very good fellow indeed, and although he had a bullet in his lung got passed fit for general service.

The Company Commander was Major de Freine. He was very slack and incompetent, but good-hearted. On the whole we didn’t fancy our chances as a section as our Company Commander and section commander were notorious throughout the battalion as hopelessly slack.

The Battalion Commander was Lieut. Col. Burnett. He was thought a great deal of in England but became very unpopular in France and lost his command after Cambrai.

The battalion as a whole had a very good name indeed and had a fine spirit, but the officers were, I thought, patchy. There were good ones there, and more came out to the front when we got to France. The others were largely men who had seen a good deal of fighting and had gone into Tanks to avoid it. Later, when the Tanks got into action, their low morale etc. let them down, and they were gradually weeded out — particularly after Cambrai. The men were a very fine lot indeed. We got a lot of training, and a good deal was expected of us from the Staff at Bovington Camp. My crew practically held the record for efficiency in their courses and had done two battle practices in which they came out very well. The course consisted of driving over a field about three-quarters of a mile long, where there were various targets. Each gunner fired ten rounds. In the last and final test, in France, over a rather harder course, my crew got the Tank Corps record of 100% hits.

On June 25th the battalion marched out of camp in full battle order at 9 a.m. and entrained for Southampton at Wool. The whole camp — about 5,000 men — turned out and cheered us off. The band played us out. The Brigadier saw us off at the station and shook all the officers by the hand. As the train steamed out, the band played ‘Auld Lang Syne’ and ‘Home Sweet Home’. We reached Southampton at about 2 p.m. and embarked at about 5 p.m. on the Australind. We steamed out an hour later, and it was getting dark as we lost sight of land. We had to lie down where we could below decks. Most people were pretty miserable, and there was not much talking. We had some bully beef and biscuits and then got to sleep as best we could.

We woke at about 2 a.m. and found we were anchored outside Le Havre. It looked a dirty, miserable place as we ourselves were not too happy! However, when the daylight came and at last we got into the dock, we felt better. We disembarked at about 3 p.m. and a little later marched up to the rest camp. Here we got quite good meals again and went off to sleep expecting to shift on up the ‘line’ shortly. We, however, stayed at Le Havre a week and had a very good time. We had bathing parades every morning. Here our sergeant-major of the company got into trouble and was returned. We were thoroughly glad to see him go, as he was a rotter. The next one we got was better, but he wasn’t much use.

At last we got orders, and one afternoon we marched to the town and on to the station. Here our train was waiting. It consisted of red cattle trucks and very red third-class carriages for the officers. We realized later that cattle trucks were better as you can lie down and get to sleep in them, but can’t do that in ordinary compartments. We moved out at dusk and passed through Harfleur just before nightfall. We didn’t know where we were going except that we were going up towards the ‘line’. We tried to get to sleep as well as possible, but in those days we didn’t know the value of getting to sleep when and where you can, so some of us didn’t bother very much. Fortunately on this occasion it didn’t matter very much.

At about 2 a.m. we reached Abbeville and here had hot tea, which was made in large cisterns on the platform for passing troop trains. At about midday we reached our destination, which, we found, was a small French village called Anvin. This was quite near St. Pol, the great railway junction, and about thirty miles behind the ‘line’. It was a very pretty place, and we were very comfortable in huts. There were an enormous number of wildflowers in the fields, and it was very pretty. As evening came on and it got quieter, we heard the guns for the first time. They sounded just like very heavy thunder in the distance. We often heard them afterwards even in full day. When the artillery opened up at all, it sounded just like the continuous but rather muffled roar of heavy transport over cobbles. On these occasions the windows used to shake and shudder with the concussion.

We did a good deal of drill and so on at Anvin and also went to Merlimont Plage, the Tank gunnery school, for battle practice courses. We had a very pleasant time there. We left the battalion in groups of about four crews and stayed at Merlimont a week. The parades were very short, and it was by the sea. When we came back from Merlimont, we drew tanks. For this we went to Central Workshops at Erin. You were given a tank, which you looked over and ran a little to see it was all right. You then drew all its equipment — telescopes for the guns, periscopes, tarpaulins, tank compass and a thousand other things. You then loaded up your tank and drove off.

As soon as the whole battalion had got tanks, we prepared to go forward. We drove our tanks to Erin from our park and there entrained them. Entraining is very heavy and tiresome work and takes an enormous time until a battalion gets expert at it. You first have to push in the tank sponsons (gun turrets), and this is heavy work if your tank is a male (with 6-pdr guns). If it is a female, you have far smaller turrets (for machine-guns only), and they are hinged and just close back into the tank, but both kinds are liable to stick. At first we used to batter them in, but later we used to get another tank to shove its nose against the turret and drive it in that way. After your sponsons are in, you drive on to the train by an end-on ramp, as per the diagram (Figure 2). The train is specially constructed, and the trucks are 8′1″ broad. As the tank is 8′½″ broad, we had to steer carefully. You can, as a matter of fact, overhang quite a lot, but you must finish up with your tank flush. You will see in a later picture how they should be. Later the battalion got pretty expert, and from the time we were all ready to go on (sponsons in etc.) to the time we were all on and chocked up was a little under two minutes.

Figure 2

Entraining tanks.

Entraining tanks.

We set off at dusk and arrived at our destination — Beaumetz — at about l a.m. This was about ten miles from the line, and we arrived just as a raid was going on. The whole place shook from the heavier concussions, and the roar was terrific to our inexperienced ears. Very lights [flares] and star shells, together with the gun flashes, helped to light up the horizon. The company (we came in a separate train from the two other companies) detrained as fast as we could. Thanks to the absolute lack of arrangements by either battalion or company commander, we were very tired. No orders had been sent by the O.C. Company who had gone on ahead, and so we prepared there and then to drive five miles to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Frontmatter

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- WAR MEMOIRS 1917–1919

- Diary

- Commentary

- Amiens

- Aftermath—Parthenope Bion Talamo

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Complete Works of W.R. Bion by W. R. Bion, Chris Mawson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Napoleonic Wars. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.