The Melodramatic Seductions of Eva Perón

Silvia Pellarolo

This study explores the phenomenon of the libidinal attraction of the public figure of the actress Eva Perón—the extremely famous wife of Argentine president Juan Perón (1945–52)—and the following of her seduced audiences, under the light of current theories of gender construction and performance. I claim that in the fictional roles of her performing career Evita rehearsed the model of the political activist she would become during the Peronist administration, in which she starred as the protagonist of a flamboyant public theatricality. Her training as an actress resulted in a melodramatic style that could be traced from her first steps performing second-rate roles in the commercial theater and films, followed by the radio soaps she read passionately in the early 1940s, to conclude finally in her declamatory gestures at political gatherings.

This unexplored corporeal rereading of this public figure facilitates the recovery of her theatricality—and complexity—as a charismatic stage and political performer who embodied a modern feminine style which had already seduced mass audiences and thus received popular consent to promote much-needed reform in the society and legislation of her country.1 For this revisionist approuch to the understanding of Evita, Judith Butler’s (1983) theories of the performative construction of gender become powerfully insightful tools.

In her introductory chapter to Bodies That Matter, Butler argues for the validation of a theoretical and epistemological reconsideration of the materiality of bodies. Her study traces the origins of Western metaphysics and the concept of representation in Plato via Irigaray, and discloses a number of exclusions in our received notions of materiality (i.e. women, animals, slaves, property, race, nationality, homosexuality), among which the materiality of the body of woman is underscored. Butler concludes by legitimating an inquiry critiqued many times for its “linguistic idealism” (p. 27), which would indeed serve as the groundwork for a political action validated by the reinscription of these exclusions in the Western truth regime.

Later in the book, she studies Slavoj Zizek’s rethinking of the Lacanian symbolic in terms of the Althusserian notion of ideology in an innovative theory of political discourse, which “inquires into the uses and limits of a psychoanalytic perspective for a theory of political performatives and democratic contestation” (pp. 20–1). This theory which accounts for the performative character of political signifiers that, as sites of phantasmatic investment, effect the power to mobilize constituencies politically, could very well serve as a critical tool to understand the iconic appeal of Eva Perón, and the exchange engendered by her performing body and the enthusiastic reception of her adoring fans.

It could be said that, in a Butlerian sense, Evita’s is a “body that matters,” as I expect to prove in a book I am writing about gender construction in modern Argentina that focuses on the theatricality of “public women.” I trace the trajectory that goes from the very popular women tango singers of the 1920s and 1930s and how their specific performative styles helped establish a modern feminine model that Evita would later incarnate, and thus take advantage of a vernacular type of female theatricality derived from melodrama, that facilitated an identificatory exchange with her audiences.2

It is impossible in such a study to disregard the issue of the “body” of Evita — considering her very public career and the overabundant dissemination of her iconography in the graphic propaganda of Peronism—and what this body represented for her constituencies (or the phantasmatic investments afforded to it). The strong symbolic value of this female body is ultimately proved by the anxious zeal of the Argentine military who overthrew her husband, president Juan Perón, in 1955, in “disappearing” her embalmed corpse from the public eye for almost twenty years.3 Evita’s is a body that matters because it becomes in the collective unconscious a synecdoche of the plight of a people, a screen onto which a community’s desires, hopes, and needs for visibility and representation are projected.4

In fact, her performative body is all we have left from her to piece together the fragments of her private persona, which remained forever a façade: phantasms of a public figure, traces of a performing diva, specters of her volition in motion reproduced in different media (films, documentary footage, newsreels, photographs). A study of Eva’s performing body will, then, following Butler, reveal its materiality and thus its political location as an exclusion of the pre-Peronist body politic. Eva Perón’s mere physical presence served as a disruptor of the conservative political theatricality, used as it was to the austerity of male uniforms of institutionalized professions. In this context the body of an actress became a dangerous sign because it carnivalized received notions of propriety in political practices.

Argentine theater historians have noticed the discrimination actresses had to endure from a fanatically conservative society: “The independent life of the actress, as well as the dangers of work that involved public entertainment, had always made that profession somewhat disreputable for women” (Guy 1991: 157).5

This discrimination was evident since colonial times, as historian Teodoro Klein records in his well-documented history of Argentine performers (1994:61), by a lack of actresses in theater troupes, due to the difficulty to attract women to a profession of ill-repute. An emblematic anecdote about the marginalization of

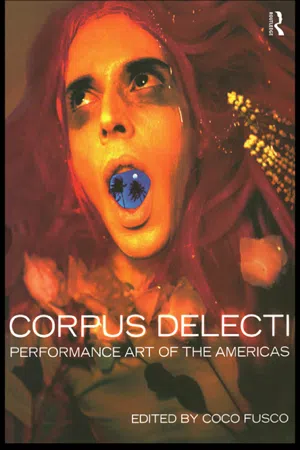

3. Peronist propaganda poster featuring Evita Duarte Perón, 1947. Text reads: “To Love is to Give Oneself, and to Give Oneself is to Give One’s Own Life.” Photo courtesy of Silvia Pellarolo.

actresses during the nineteenth century is told by the tragic story of a second-rate soprano surnamed Verneuil, who, while performing the role of the reverend mother of an abbey in the operetta Mousquettaires au couvent, transgressed the conventions of her role, and in what was perceived by the shocked audiences as an “attack of mental alienation” (Urquiza 1968:25), raised the skirt of her habit and started to dance “a furious can can.” Her punishment for such a sacrilegious subversion cost her her freedom: she was locked up in a lunatic asylum for the rest of her life.

Music-hall performers were said to be given to clandestine prostitution; as they received “absurdly low wages,” they were obliged to “supplement their earnings…by practicing prostitution” (Guy 1991:149). Actresses who sang in low-class music halls or theaters were frequently “obliged to associate with the audience…and to incite the men to drink” (p. 149). This practice became widespread with the success of the cabaret culture in Buenos Aires, during the second decade of the twentieth century. In venues such as the Royal Theater, which was situated in the ground floor of a very famous cabaret, in the context of which, and as part of the clauses of their contracts, “after the entertainment [wa]s over, …the young actresses [we]re expected…to ‘entertain’ the men who [we]re present” (p. 149).

These social values that condemned women performers, and perceived them as a threat to the hegemony of the patriarchal society, were the backdrop of the collective anxiety produced when the coupling of an actress as Evita and a disruptor of political conventions as her husband, Juan Perón, was shamelessly exhibited in the context of politically charged public performances. The evident disruption of the cozy boundaries between the private and the public that the Peróns promoted by means of their scandalous liaison is foregrounded by Donna Guy, who asserts that

Much of the class anger directed at Evita and Juan Perón in the 1940s and 1950s derived from the same value systems that had generated the lively debates about prostitution and popular culture before 1936. That same fear of female independence, of lower-class and dubious women’s taking control over their lives [and bodies], of their joining with society’s most dangerous men in a social revolution, all came true within the context of the Peronist years, 1943–55, and in this way fiction became a reality.

(1991:173)

This blurring of the boundaries between reality and fiction, the overlapping of theater and life, that the carnivalization of Peronism represented in decorous Argentina, is even perceived in the historical accounts of that era. Such is the case of Navarro and Fraser’s biography of Evita (1996), in which the use of the theatrical simile becomes redundant when describing the spectacular dimension of Peronism and the fascination produced on the audiences it summoned.6 Probably modeling the spectacularity of fascism as an efficient way of staging a rustic vernacular theatricality repressed by the illustrated elite more prone to the mimicking of elegant French models, the propaganda machine of Peronism was a savvy interpreter of the benefits of the interconnection of mass culture and politics, with the intuition that in order to revert the hegemony of the oligarchy the ethic and aesthetic values and images of the rising class and emerging sector of consumers should be disseminated by means of the expanding culture industry. Thus, Peronism’s revalorization of “popular national traditions, considered [by the Europeanized liberal class in power], to be synonymous with backwardness, obscurantism and stagnation” (Laclau 1977:179), as efficient counterhegemonic practices and productions that would disrupt the coherency of a social imaginary constructed in oppostion to its deepest cultural roots.7

In this epic play, Eva Perón assumed the role of the standardbearer of this rising class, her performing body an icon which—following a melodramatic tradition —fulfilled vicariously collective desires of representation and agency. The success of her acting career, her training field from 1935 to 1945, that consisted of twenty plays, five movies and twenty-six soap operas (Navarro and Fraser 1996:48), could be read as a dress rehearsal the prominent role she would perform as the notorious wife of a popular president. Such was the case in the radioteátro scripts she performed for Hacia un Futuro Mejor (Towards a Better Future), an agitprop celebration of the 1943 revolution that had taken Perón and other reformist military men to power. Broadcasted by Radio Belgrano, and authored by the same men who would later write many of the Peróns’ political speeches, the program aired on the night of August 14,1944, titled “The Soldier’s Revolution will be the Revolution of the Argentine People,” presented Eva’s debut as a Peronist militant. “Over the sound of a military march” a speaker announced

Here, in the confusion of the streets, where a new sense of purpose is coming to be born…here, among the anonymous mass of working, suffering, thinking, silent people…here, in the midst of exhaustion and hope, justice and mockery, here in this shapeless mass, the driving force of a capital city, nerve centre and engine of a great American country …here she is, THE WOMAN…

(Navarro and Fraser 1996:43)

With a melodramatic tone, Evita talked next about the wonders of the Revolution, which she claimed had come to cure “the sense of injustice that makes the blood rush to one’s hands and head”; a Revolution that “was made for exploited workers,” due to the “fraud of dishonest politicians,” because the country was “bankrupt of feeling, at the verge of suicide” (p. 43). Her training in this excessive verbal style, with its virtuosity of gradiose hyperboles and contrasts, the strong enunciation of a Manichean worldview, and the delivery of clear didactic and moralizing messages, would prove to be extremely effective during her forthcoming public appearances, in which she spoke to the hearts of the masses, thus satisfying, as it happens in populist regimes, the “rising expectations” of the people, with an ideology and a style that appealed directly to their emotions (Laclau 1977:152).

Another interesting illustration of this “rehearsal” of her political role is the movie La Pródiga (The Prodigal; completed in October 1945, but sequestered from public viewing until 1984), in which she portrayed a repentant sinner who, as part of her penitence performs acts of charity; a rich widow who, in a very feudal way, is prodigal with the good peasants of her domains, who address her in anticipation to her political career as “hermana de los tristes, madre de los pobres” (sister of the sad, mother of the poor). “Evita liked the film and also the stereotype of suffering, sacrifice and destruction she had portrayed,” declare Navarro and Fraser (1996:48); this was said to be her favorite role in her performing career, a “memory of the future” in Alicia Dujovne Ortiz’s words (1995:96). No wonder that in the fiction of Eloy Martínez’s Santa Evita the first lady is presented delighting in the solitary pleasures of its private screening.

Evita’s female agency, charisma, and stage presence undoubtedly derive from her desire to please the public, to perform legitimacy and thus become visible before a captive audience. As an illegitimate child, she carried inscribed on her body the unsurmountable desire to be acknowledged, to be seen; a desire that, according to Dujovne Ortiz, became the mobilizing force which propelled her forward (1995:95). In her autobiography, La Razón de mi Vída, Eva confesses that since her early childhood, she always wanted to recite (declamar): “It was as if I always desired to say something to others, something big, that arose from the bottom of my heart” (1996:24). In fact, there is a very interesting childhood photograph that captures “the creative Duarte children” dressed up in costumes for the Carnival celebrations in the town of Los Toldos (de Elía and Queiroz 1997:23). To the l...