Chapter 1

The History and Status of a Theoretical Debate

John U. Ogbu

In a joint 1986 publication, Professor Signithia Fordham and I first argued that cultural frame of reference and collective identity should be included among the widely recognized, interlocking societal, school, and community factors known to influence minority students’ school performance. A cultural frame of reference reflects an ethnic group’s shared sense of how people should behave, and a collective identity expresses a minority group’s cultural frame of reference. In some situations, an ethnic minority group’s collective identity may oppose what its members perceive as the dominant group’s view of how people should act (Ogbu, 1982a, 2000; Ogbu & Simons, 1998). When the cultural frame of reference is oppositional, it can adversely affect an ethnic minority group’s schooling. Students may not engage in certain behaviors that are conducive to doing well academically to avoid having their peers identify them with the dominant group.1

Based on Fordham’s research at Capital High School in Washington, DC, we reported in our joint article that efforts to steer clear of such identification led some minority students to avoid certain attitudes and behaviors that their cultural frame of reference associated with Whites. Such avoidance contributed to the minorities’ low school performance. We called the students’ attempts to resolve the tension between the school’s demands to behave in ways that result in academic achievement and their peer groups’ demands not to do so “the burden of ‘acting White’.”

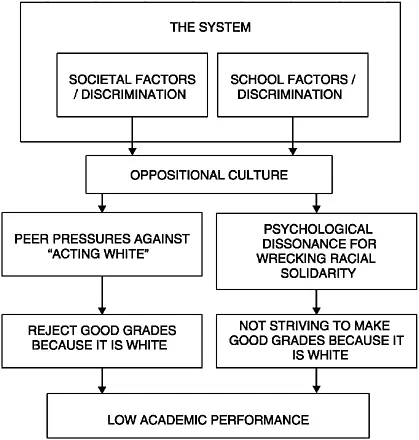

The thesis of this joint article was that (a) discrimination by society (e.g., denial of minorities’ adequate rewards for their educational accomplishments through employment barriers and lower wages), (b) discrimination in the education system (e.g., school segregation, inferior curriculum, low teacher expectations), and (c) Black American responses to the mistreatment by society and school (e.g., disillusionment, lowered academic effort, mistrust of the schools) all result in low school performance; however, (d) an oppositional collective identity and an oppositional culture frame of reference also contribute to low school performance because minority students avoid (so-called) White attitudes and behaviors conducive to academic success.

The purpose of this book is to further broaden our understanding of the current debate on the achievement gap between Black and White students and bring together various perspectives on it. My research and studies by others have shown that oppositional collective identity and oppositional cultural frames of reference influence minority students’ school performance. These two factors need to be examined to better understand school performance and variability within given minority groups, as well as among minority groups in multiethnic societies.

There have been many criticisms of the 1986 article, even though it has been very influential. Although the intent of this volume is to explain my position in the persistent debate on the achievement gap, I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge some of the criticisms of the FordhamOgbu article as well as those of my own cultural-ecological model (CEM), which is often confused with the 1986 thesis.

Critics have argued that the Fordham-Ogbu thesis has many limitations. Unfortunately, many critics have lumped together my CEM and the 1986 thesis and treated them as one and the same. Hence, my entire body of work, as well as my theoretical formulations, has been mislabeled or referred to as oppositional culture theory or “acting White” theory. Some have argued that the theory does not explain within-group differences; that it neither adequately addresses the impact of societal racism and discrimination, nor takes into account the daily school experiences of Black students; that it fails to distinguish between cultural and instrumental assimilation; and that its treatment of culture is too structural and static, and not sufficiently dynamic. Other critics have labeled the theory as a deficiency model that does not explain variability among groups, or have argued that it focuses too much on less successful blacks. Also, critics have claimed that the theory does not adequately address racial identity and successful academic outcomes.

Some groups have criticized the theory for being too historical or structural, while others have argued that the theory does not understand Black history and education. Yet, another group of critics, particularly quantitative researchers, have contended that there are actually no differences between Blacks and Whites on a number of key indicators. They have reported no evidence of discrepancies between Black students’ verbal responses and their actual performance and, in fact, found no evidence of oppositional culture.

The above list of criticisms is not exhaustive. I have tried in many of my publications to respond to or clarify some of the issues (1974, 1989, 1992, 1994, 1997, 2003; Ogbu & Simons, 1998). In reviewing the criticisms on opposition culture and schooling, a pattern became evident to me. First, many critics failed to distinguish among my cultural-ecological model, the Fordham-Ogbu thesis, and Fordham’s perspective, and second, they constructed or replaced the thesis of the 1986 article or CEM with their own interpretations (see Figure 1.1). Their criticisms have rested on flawed interpretations of my work—the lumped formulation that is the amalgam of my cultural ecological model and the Fordham-Ogbu thesis.

To enhance the contributions of oppositional culture scholarship to understanding the patterns of minority school performance, I will briefly describe the evolution of collective identity and cultural frames of reference as conceptual tools in the study of minority education. Next, I will explain how the three perspectives on collective identity and schooling (my cultural-ecological model, the Fordham-Ogbu thesis, and Fordham’s theory) differ from each other. The chapter then concludes with an overview of the remaining chapters in this volume.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF CONCEPTUAL TOOLS

The concepts of collective identity and cultural frame of reference came from several sources. The first was my fieldwork in Stockton, California between 1968 and 1970. While conducting that study, I found that some Black and Mexican American students did not want to do their schoolwork or speak Standard English because they considered these behaviors “White” or “Anglo.” One African American parent reported a discussion she had with a Black student about behaving like White people. The student accused her of “thinking like a White person” because she advised him to go back to school and graduate. My informant went on to say:

This is what that young boy told me…. He said, “You’re thinking like the White man. Because what is an education?” He said, “I can go out right now and come back with 100 suits or diamond rings.” I said, “Oh yeah! You probably could, but you got to know how. You got to be smart, you know?” He said, “You don’t have to have the White man’s education to get to be rich or to get what you want.” … This is the way he seemed to think. I was telling him, I said, “Well!” It was two of us and we had a big long discussion and … I had to stop. And I was saying to him, “Don’t you think that you ought to go back to school?”

Other Black school personnel also reported on how they often advised Black students that even though Standard English is the White man’s language, they should master and speak it in order to do well in school and to get a good job after they graduate. One Black school administrator in Stockton used the following slogan to drive home this message: “Do your Black thing, but know the White thing, too.” During an interview in 1970, this informant went on to explain why it is important for Black Americans to master Standard English. In his words,

Figure 1.1 Critics’ construction of the cultural-ecological model.

You hear a lot of people say, “Well, why should I speak the White man’s language?” Well, [the Black man has to because] he’s living in the White man’s world. And the White man controls the resources. He controls the finances. He controls all of these things. And you know, I’ve often said, “By Jimmy! I want to speak his language [i.e., Standard English] better than him. I want to be able to do the things he’s [the White man’s] doing better than him.” And the thing is, this is his [the White man’s] world. Now if I’m living in Africa, I’d learn the African thing. But now that we’re living in America in a White racist society, we have to learn his language if we’re going to do it [succeed] because—you know, you can make it on Black people’s [resources]—but not many of them do. And I believe that in this American society a Black man can use all these White man’s resources. And you don’t have to degrade yourself. I don’t feel that I’m degrading myself a heck of a lot in my lifetime to learn the White man’s way. You can still maintain your dignity. But I think that many of the kids … this is where a lot of the kids get sort of mixed up, you know … they say, “Well, we want to do a Black thing.” Well, fine, I believe in the Black thing. But you’ve got to learn that White thing, too. “Do your Black thing, but know that White thing, too.”

Black adults and students expressed their opposition to “the White man’s ways” in other contexts, too. For example, during my research in Stockton, they organized rallies and conferences at which some speakers condemned “the system” and objected to “doing the White man’s things” required by that system. I was invited to speak at one of these conferences, but the day before my presentation I was uninvited because, as I was told, I was too White! I found out later that because of my university education at Berkeley, I was perceived as behaving like White people.2

Another factor contributing to the development of the concepts of collective identity and cultural frame of reference was my review of ethnographic studies of U.S. minority students’ experiences as compared to the experiences of children attending Western-type schools in developing countries. Educational anthropologists and other researchers in the 1970s emphasized the underlying role of cultural differences or cultural conflicts in minority students’ school adjustment problems and their academic failure (Burger, 1968; Erickson & Mohatt, 1986; Gallimore, Boggs, & Jordan, 1974; La Belle, 1976; Lewis, 1979; Philips, 1976). They recommended culturally compatible teaching and learning as remedies for minority groups’ educational problems. Similar remedies were recommended for solving the educational problems of children in developing countries (Gay & Cole, 1967; Inkeles, 1968; Spindler, 1974). However, based on my research on minority education in the United States (Ogbu, 1974) and my review of data on the cultural experiences of school children in Africa, I did not think that the cultural problems of minority students in the United States were similar to those of students in the developing countries (Heyneman, 1979; Imoagene, 1981; Malinowski, 1939; Musgrove, 1953).

An additional key source in my development of the concepts of collective identity and cultural frame of reference consisted of the ethnographic studies of U.S. minority school experience conducted by educational anthropologists and other social scientists in the United States. These studies compared the experiences of U.S. minorities to those of children in developing countries attending Western-type schools. Another valuable source of insights was the literature on revitalization movements among colonized and oppressed people (Lanteracnni, 1967; Penfold, 1981; Sundkler, 1961; Thrup, 1962).

Searching for Concepts to Capture Observations

As a result of my observations in Stockton and the insights I gained from the literature cited above, I began to think that some minorities in the United States and elsewhere perceived and interpreted their cultural practices as alternatives to those of the dominant group; they viewed theirs as a kind of alternative culture. The minorities seemed to prefer behaving in ways they considered different or opposite from the ways of the dominant group, which they considered their oppressor.

I first presented this perspective on cultural differences and schooling in 1979 during an invited address at the First Jerusalem International Conference on Education at the Hebrew University. In that address, I distinguished alternative cultures from non-alternative cultures in minority groups’ responses to the cultures of dominant groups. I later presented a revised version of the paper in 1980 at the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association. In that paper, which was eventually published (1982a), I introduced a typology of cultural differences, consisting of universal cultural differences, primary cultural differences, and secondary cultural differences.

I defined universal cultural differences as those differences between home culture (and language) and school culture (and language) that every child encounters upon entering school. Regardless of their cultural background, all children make a transition from home culture to school culture and thus confront these differences.

Primary cultural (language) differences exist before two populations come together, for example, before members of a population (e.g., immigrants) became a minority group in the United States. Bearers of primary cultural differences experience problems in teaching and learning, as well as social adjustment, because they bring to school their customary behaviors, as well as the assumptions underlying those customary behaviors, that are different from those of the public school, as well as the dominant group members who control the school (Musgrove, 1953; Ogbu, 1982a).

Secondary cultural differences are what I previously designated as alternative cultures (Ogbu, 1979). These differences usually come about after group members have been forced into an oppressed minority status. Secondary cultural differences also characterize the cultural responses of some colonized and ...