![]()

Part I

THE INTERSYSTEM MODEL AND THE THEORY IN PRACTICE

The first section of this book consists of two chapters. Chapter 1 describes the theory on which the book is based. The remainder of the book consists of case material which illustrates the application of the theory. The reader will find the theory chapter is densely packed with new concepts. Much of the material will be new and the reader may need to read this chapter twice to comprehend the concepts. This chapter also contains a Glossary and an Outline at the end, in order to assist the reader in assimilating the concepts.

The concepts in this chapter have universal applicability in couple therapy. The main thrust of the chapter is to promote integration among different theories of couple and family therapy. Thus, readers will not be asked to sacrifice any of their theoretical background. Rather, they will be given a theory that allows the clinician to continue building a richer theoretical perspective. This model is comprehensive enough to permit the clinician to integrate the individual, interactional, and intergenerational aspects of the client-system in both assessment and treatment. The reader who is looking for simple answers and approaches, with a singular focus, will not find it in this approach. The Intersystem Model is challenging, intellectually and clinically, but the clinician who utilizes it will be able to think about the client-system at multiple levels, while directing treatment at one issue at a time.

Chapter 2 describes the assessment and treatment of a couple over a number of years, for a variety of diverse yet core issues, and at a variety of levels. Unlike the chapters in Part II, this case presentation includes significant material from the clients themselves, which illustrate the applicability of the theory of the Intersystem Model. It demonstrates the need for an integrated and dialectical approach to the assessment and treatment of the couple’s individual, interactional, and intergenerational issues. With this particular case, the flowing back and forth between surface and depth; between past and present; between him and her; between affect, cognition, and behavior; and between the individual, the interactional, and the intergenerational, created a rich therapeutic milieu that permitted significant growth and change for the couple.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Intersystem Model: An Integrative Approach to Treatment

Gerald R. Weeks

The purpose of this chapter is to describe the therapeutic model on which this book is based. Dialectic metatheory is the philosophical basis for this model. While psychology and systems of family therapy have traditionally borrowed heavily from the natural sciences, such as physics, this chapter begins with the assumption that the natural sciences have been a poor model. The natural sciences view phenomena in linear (cause-effect) terms and strive to break complex phenomena down into fundamental units (a molecular approach). In marital therapy, a theory is needed that allows us to view the couple as an interlocking system and as intrinsically connected to many other social systems. The best metatheory to meet this goal is dialectics. This chapter will describe how to use this philosophical theory in a psychological and pragmatic way.

The Intersystem Model is a comprehensive, integrative, and contextual approach to treatment. Whenever a couple (or for that matter any other client-system)is being treated we believe it is essential to simultaneously consider three systems: the individual, the interactional, and the intergenerational, all within the context of the society and its history. Later in this chapter, these three systems will be considered in terms of how they fit together in the treatment.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The development of the systems theories and therapies has represented a major paradigmatic shift in psychotherapy. These new therapies all represented a shift away from the individual and intrapsychic theories developed and employed by Freud and the psychoanalytic/dynamic therapists. The systems theories all share the concept of the individual-as-part-of-the-system and they focus on interpersonal variables.

The past 30 years has been the “systems era” in the history of psychotherapy. In this short period of time, eight major schools of family therapy have developed, which Kaslow (1981) grouped under the following headings: (a) psychodynamic/analytic; (b) Bowenian; (c) relational or contexual; (d) experiential; (e) structural; (f) communications-interactional; (g) strategic-systemic; and (h) behavioral. These schools of thought all share some basic assumptions about the nature of dysfunction and treatment, but they are clearly different in content. Unfortunately, some of these school were originally presented as if they were to be used exclusively, without “cross-fertilization” from others (see Gurman & Kniskern, 1981).

However, the practice of marital/family therapy has been much different than the theory. In practice, the clinician is rarely a theoretical purist and many practitioners have moved toward a position known as technical eclecticism, i.e, taking what works from many different approaches and using it in their treatment. In an effort to bring theory into line with what clinicians were already doing, a few theorists started to develop integrative approaches to treatment. This effort started in the mid-70’s and resulted in a number of papers and books.

Kaslow (1981) advocated a dialectic approach to family therapy in which practitioners could draw “selectively and eclectically” from various theories. Duhl and Duhl (1981) developed an “integrative family therapy” which looked at various levels of the system, such as developmental level, individual process, and transactional patterns. Their discussion focused primarily on how the therapist thinks and intervenes. Berman, Lief, and Williams (1981), staff members of the Marriage Council, published a chapter on marital interaction and how several theories could be integrated therapeutically. They discussed combining contract theory, object-relations theory, multigenerational theory, systems theory, and behavioral analysis within a developmental and therapeu-tic framework. In addition, other efforts have been made. These include: Hatcher (1978) on blending gestalt and family therapy; Abroms (1981) on combining medical psychiatry and family therapy; Stanton (1981) on integrat-ing the structural and strategic; Lebow (1984) on the need for integration; Duncan and Parks (1988) on the integration of strategic and behavioral; and, Pinsof (1983) on an integrative problem-centered approach.

The problem with all of these approaches and others not cited above is that they fail to meet the criteria for being truly integrative as described by Van Kaam (1969), and described in the next section. The integrative movement in family therapy has actually been a movement toward technical eclecticism. Theorists have been attempting to find a way to “integrate” two or more theories and have not been attending to the need to consider both the “founda-tional construct” and the “integrational construct” noted by Van Kaam. For the most part, the best efforts have been directed toward constructs that are integrational, such as a theory of interaction to unify theories (Berman et al., 1981), but without clearly developed foundational constructs. The weakest attempts have been simple efforts to rationalize what is done in clinical practice. For a brief review of the efforts made toward integration the reader should consult Case and Robinson’s (1990) article.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE INTERSYSTEM MODEL

The best word to describe the Intersystem Model is that it is integrative. Integration refers to the act of making a whole out of parts. The word is derived from the Latin integratus, which means to make whole or renew. The principles for developing an integrated or comprehensive psychology were developed in a seminal book entitled Existential Foundations of Psychology (van Kaam, 1969). The author pointed out that psychology consisted of many “differential” theories of behavior. Each theory focused on behavior from a different perspective. As theories proliferated there eventually arose a need for some unification. The history of psychotherapy and marital therapy has followed this same course of development, as we shall shortly show.

Two constructs are needed for the creation of a comprehensive theory—the foundational and the integrational. The foundational construct provides the frame of reference for the integration of the phenomena from various differ-ential theories. This construct requires a close examination of the philosophi-cal assumptions on which the theories are built. Interestingly, family therapists have become interested in this endeavor in the last few years and a number of articles have been published on epistemology (see Weeks, 1986).

The integrational construct is that which is used to unify disparate phenom-ena. For example, organisms learn to respond to their environment in a number of specific ways. The constructs of operant and classical conditioning help to explain these patterns of responding in a way that allows us to make sense of different instances of learning.

In developing the Intersystem Model, dialectic metatheory served as the foundational construct and three integrational constructs were used: (1) paradox as a universal aspect of therapy; (2) the spontaneous compliance paradoxes, i.e., affirmation and negation paradoxes; and, (3) amodelof social interaction based on research in social psychology.

THE FOUNDATIONAL CONSTRUCT OF THE INTERSYSTEM MODEL: DIALECTIC METATHEORY

As noted, the foundational construct refers to the philosophical assumptions underlying a particular theory. It is not the theory itself, but rather the underlying concepts. It is, literally, the foundation on which a theory is built; thus, it is called metatheory.

Every theory of personality and psychotherapy is guided by an implicit or explicit theory. In most instances the theory is implicit, and, hence, not easily examined or questioned. The Intersystem Model is based on dialectic metatheory. A metatheory is a theory of theory. It is the philosophical underpinning on which a specific theory is built.

Dialectic metatheory is not new in psychology, but it is rarely used in formulating theories of family therapy (Rychlak, 1968). Weeks (1977) was the first to publish a paper that explicitly described a dialectical approach to intervention. In 1984 Bopp and Weeks published a paper that examined dialectic metatheory in family therapy. This analysis showed that some of the basic concepts offamily therapy such as “system,” “relationship,” “reframing,” “double-bind,” “paradox,” and “change” are defined in terms of dialectic metatheory.

The term “Intersystems Approach” (now, Intersystem Model) was actually coined in a paper that was part of a special edition of the American Journal of Family Therapy on philosophical and pragmatic issues in the field (Weeks, 1986). The Intersystems Approach was then described as a synthesis between two approaches—the individual and the systems. In traditional dialectical thinking, the individual pole was the thesis, the systems pole the antithesis, and the Intersystem Model the synthesis. This particular description is not intended to suggest that dialectics is as simple as thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Dialectic metatheory is a complex philosophical system unto itself. In this chapter, we will be considering the dialectical theories of two psychologists, Riegel and Bassaches.

Riegel was one of the most influential dialectical psychologists in the 70’s. He was a developmental psychologist and the editor of the journal, Human Development, where many of the papers on dialectics were published. Riegel (1976) had developed a theory of human development that stressed the need to consider four concurrent temporal dimensions: (1) inner-biological; (2) individual-psychological; (3) cultural-sociological; and (4) outer-physical. Different theories of family therapy stress these dimensions differently. From Riegel’s perspective, a comprehensive theory would need to give attention to each of these four aspects of functioning.

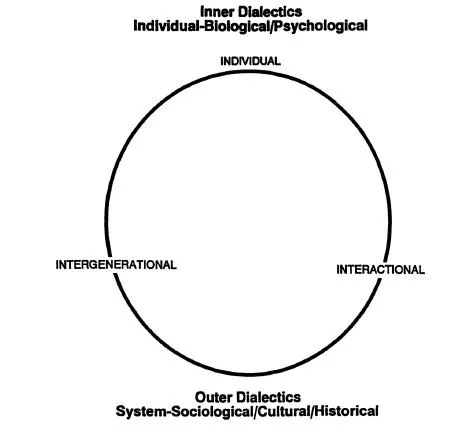

The Intersystem Model has emerged as an attempt to consider all dimen-sions of the couple/family. The Intersystem therapist is much like the conductor of an orchestra. Unlike the pianist who is playing alone and wishing to create harmony within one section or system, the conductor wishes to create harmony across different sections or systems. In order to relate Riegel’s (1976) concept of dialectics to couple therapy, we have chosen concepts already familiar to the clinician. Thus, we stress the assessment and treatment of the couple from the perspectives of the individual, interactional, and intergenerational. The figure below shows how “inner-” and “outer-dialectics” are related.

Although Figure 1 does not show it, we also include considerations that are cultural-sociological, such as race, ethnicity, economics, and the outer-physi-cal such as living conditions and natural disasters. These aspects of the couple should be reflected in the Case Formulation (Weeks & Treat, 1992) developed by the therapist.

Bassaches’ (1980) work on dialectics is much more psychologically sophis-ticated than Riegel’s, and offers us much more focus and many more specifics. His definition was encompassing in that it lent itself to motion and change, and applied to both ontology (a branch of philosophy concerned with the study of being) and epistemology (a branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge). He defined dialectic as: “developmental transformation (i.e., developmental movement through forms) which occurs via constitutive and interactive relationship” (p. 46). Bassaches was primarily interested in cognitive operations.

Figure 1. Inner-outer Dialectics

He formulated a new stage of cognitive development called dialectical thinking, which allow us to comprehend the “dynamic relations among systems” (p. 401). The ability to think dialectically is an absolute must for a systems therapist. Without this ability the therapist would not be able to conceive of a system, see the dynamic relationships within the system, or comprehend the contradictions that exist within systems and help to bring about change.

Bassaches (1980) argued that dialectical thinking involves 24 specific ways of conceptualizing that can be organized into four major categories. These four categories are motion, form, relationship, and meta-formal integration. The dialectical assumption is that motion or change, not inertia, is the fundamental tendency. No external force is required for change to occur. Reality is not a linear series of discrete and unrelated parts. It is motion, change, and interrelated activity, which is fundamental.

His concept of form emphasizes context. A dialectical description of phenomenon encompasses the structural, functional, and equilibrational quali-ties. Behavior is seen as a complex phenomenon with all qualities being interrelated. There may be periods of homeostasis, but qualitative changes inevitably follow. When describing couples, one does not change unidirec-tional phenomena. This view would be considered linear. A couple therapist emphasizes the circular nature of interactions—how one partner influences the other and is in turn influenced. This is one important aspect of “form.”

The dialectical concept of form is pervasive in family therapy. For example, when describing the symptom, the couple therapist may utilize all three of the specific ways of conceptualizing within the category of form. These specific ways of dialectical thinking include: 1) contextualization; 2) equilibration; and 3) contextual relativism.

Contextualization refers to seeing phenomena with a contex...