![]()

1 Corporate Identity

The Bauhaus in Dialogue with the Public

The history of the Bauhaus has often been told and is easily accessible elsewhere.1 Reviews emphasize the role of the art school, oscillating between reform and avant-garde; it was the first art school to be reformed after the First World War, having resumed teaching in the new Republic in 1919. The leading figure was architect Walter Gropius, who was appointed director on April 12 and soon converted the traditional institution into a unique collaboration of artists and craftsmen under one roof. He first appointed Johannes Itten, Lyonel Feininger, and Gerhard Marcks, to be followed later by Goerg Muche and, representing the most prominent Bauhaus staff, Paul Klee, Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky, and László Moholy-Nagy. These artists gave rise to the public perception of the Bauhaus as a cradle of the avant-garde in the twentieth century; however, it was not the individual brilliance of the Bauhaus masters but their mutual contribution to an ultimate goal that made the school singular in its time. Despite a hostile local public at all three of the Bauhaus locations—Weimar, Thuringia (1919–1925); Dessau, Saxony-Anhalt (1925–1932); and Berlin (1932–1933)—it proved successful, in different ways, in uniting art and technology: first in an expressionist period and then in constructivist and functionalist movements.2

Swiss urbanist Hannes Meyer joined the Bauhaus faculty to head the new Architecture Department in 1927; he replaced Gropius as the school’s director just a year later, in April 1928. His architectural projects and theoretical writings preceding his appointment established his reputation as an innovative architect who tried to address new social challenges with an architecture that stressed function and collectivism over aesthetic concerns and individualism. His accomplishments as director—including a reorganization of the curriculum, increasing revenues through mass-production of Bauhaus designs, and drawing large numbers of new students to the school—have been overshadowed by controversies about his politics and his dismissal by the municipal authorities in August 1930.3 Dividing the Bauhaus era into periods based on the terms of its directors, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe also had little more than two years until the Bauhaus finally closed, in 1933, when the Nazi Party came into power. His leadership was characterized by an unfortunate start (students on strike owing to Meyer’s dismissal) and an even less fortunate end as a private school in a Berlin backyard, poorly financed and under observation by the Gestapo.4

Although there are good reasons to appreciate the Bauhaus solely for its merits in art and design, it should not be overlooked that all the individual and collective oeuvres were possible only because the Bauhaus operated more or less productively as an institution of higher education. On this assumption we may argue with the Communicative Constitution of Organization (CCO) movement5 that organizations can be conceived as being communicatively constituted—or to quote James R. Taylor:

I have never been able to figure out how there could be an organization in the absence of communication, existing before communication, and on material plane distinct from it. It seems self-evident to me that organization is a product of communication, and totally dependent on symbolic sense-making through interaction for its mere existence.6

With regard to the Bauhaus, thus, we may ask what role communication played in the developments mentioned here, particularly beyond the merely aesthetic considerations usually applied in evaluating the Bauhaus’s merits. If this perspective is instrumental in assessing the Bauhaus as an organization—and we believe this to be the case—the evidence accumulated in this book should help future research to explain the Bauhaus’s mode of operation and thus provide a distinct framework for our understanding of the ups and downs characterizing this institution, perhaps the major cradle of modernism in the twentieth century.

After the Bauhaus closed in 1933, its founding spirit as well as its principles of education and design survived, even without the spiritus loci of the Bauhaus building and a regular school. The Bauhaus moved from an institution to a “community” as we understand it today: Most of its members, harassed and menaced by Nazi rule, were displaced and scattered all over the globe, but for decades they managed to maintain personal networks of support and inspiration. Deprived of its physical hub and its norms, both requisites of an institution,7 what remained of the Bauhaus were its leading principles and values as adapted by the individuals who had left it behind. Thus the group of “Bauhäusler” became a “Bauhaus community”—a group of individuals engaged in mutual relationship to pursue shared interests—and their interactions were, of course, dominated by communication over time and space. For the survival of the Bauhaus community, the maintenance of relationships by communication media was crucial, bridging the gaps between local networks of varying consistence and endurance.8 For example, regarding the communications of former Bauhaus master Gerhard Marcks, spanning the different periods of the Bauhaus movement, previous analysis has distinguished networks including intellectual groups, chains of masters and students, and ties of rivalry.9

If we accept the vital role of communication for institution building on the one hand and, on the other, the prevalence of Bauhaus networks of communication relating its members over time under the umbrella of a shared mission, it appears promising to analyze the communication within, around, and outside the Bauhaus in order to better understand its performance. Whether the Bauhaus can be considered to have been a success—in its time or from a today’s point of view and according to which criteria—is still a controversial issue. In an early data-based account, Folke Dietzsch, who began his work under the scientific structures of the German Democratic Republic, aimed at collecting the names and biographical details of all Bauhaus students identifiable from the official sources in Weimar and Dessau.10 He offers a wealth of data that might be suited for an assessment; for instance, he reports that looking at the graduations, only about 15 to 20 percent of all Bauhaus students actually obtained a diploma or a certificate of apprenticeship.11 This low rate of completed studies can be seen as a failure, given the school’s general objective of educating young people. However, in their later lives, a considerable number of Bauhaus students were able to establish their own studios, agencies, or architect’s offices; in retrospect, most of the Bauhäuslers stated that their studies at the Bauhaus—whether completed with a grade or not—were formative for their future careers and essential to their definitions of success in their personal lives.12 According to other criteria (e.g., share of international and female students respectively, relationships between masters and students, number of guest lectures, etc.), the Bauhaus was in the vanguard, conceding that its aesthetic concept remains in dispute even today. With regard to its effects on global issues of art, design, and urban development, former Bauhaus students have left their traces in a many nations.13

In retrospect, even critical accounts of the Bauhaus acknowledge the tremendous impact it had throughout the years of its chequered reception in various contexts.14 The two main indicators of its inefficacy, however, cannot be argued away: The Bauhaus was twice chased away from its locations in two different German states and was led by two different directors. And for a comprehensive view, we cannot disregard the fact that governmental structures in these environments were based on democratic elections. So despite our ongoing sympathy for the Bauhaus as representing a refuge of cultural opposition against conservative and fascist forces in Weimar Germany, public opinion at that time was mixed to say the least. This leads us back to the basic notion of this book mentioned above—to analyze the contribution of communication processes in their broadest sense to the Bauhaus’s success as well as its failure. From today’s knowledge, we argue that the Bauhaus can be understood as an organization to which, for analytic purposes, today’s standards of “corporate communications” can be applied, being well aware of the misleading description of the Bauhaus as a corporation. While a more correct designation would instead label the Bauhaus as an institution or just an organization, we decided to preserve the technical term of corporate communication (and, consequently, corporate identity, design, and behavior) because they are well established in previous research, and applying these concepts exactly accounts for one major novelty in Bauhaus research.

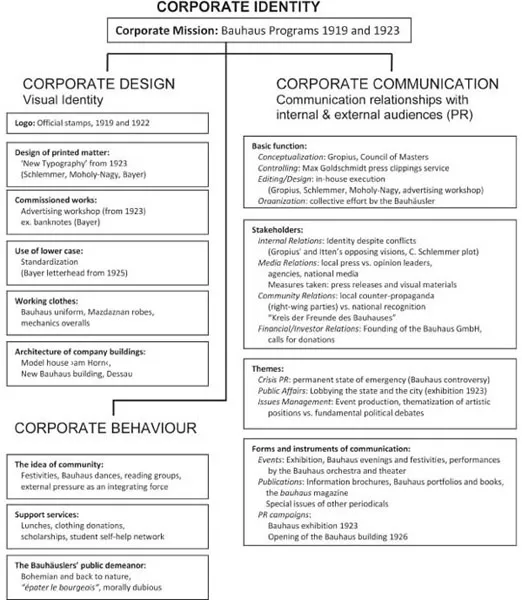

Within this framework (see Figure 1.1) the activities of what we would call public relations—the communication relationships with internal and external audiences—deserve our special attention because they put aspects of corporate design and corporate behavior into a perspective that may constitute a link between the approaches in art history and social science.

Figure 1.1 The Bauhaus in public communication—an overview (author’s diagram).

Public Relations in Germany of the 1920s

To assess the significance of the Bauhaus’s public relations more adequately, it seems useful to look at the field’s state of development in Weimar Germany in general, which allows for a judgment not only from a today’s perspective but also in relation to the contemporary background. After World War I, Germany experienced a growing awareness of public relations,15 although one cannot speak of a professional field at that point.16 The early-twentieth-century upswing in the evolution of public relations, in part a response to changes in modern journalism, can be traced back to two main factors: First, many observers (and affected parties) believed that the open partisanship of many media, especially the so-called opinion press, was leading to distorted coverage or a complete lack thereof; second, it became clear that in emergent modern civil societies, large target groups and audience sectors could be reached only via media such as the popular press (or later the radio).17

Edward L. Bernays’s primer titled The Art of Public Relations, published in 1928, first established public relations—then referred to as “propaganda”—as a broad-based instrument of strategic communication.18 He devotes two separate chapters to the spheres of education and art, at whose intersection the Bauhaus operated. He clearly identifies dependency on the state and/or sponsors as a determining factor, while describing art as minority rule by means of pressure on public opinion. For this reason, he argues, public relations plays an especially important role in this field: “In applied and commercial art, propaganda makes greater opportunities for the artist than ever before.”19 He ...