- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

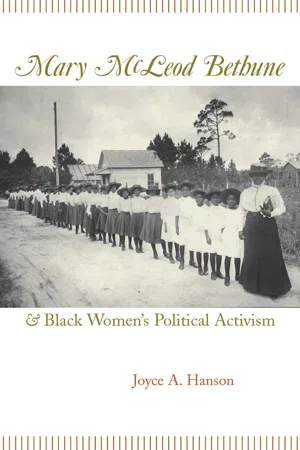

Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women's Political Activism

About this book

Mary McLeod Bethune was a significant figure in American political history. She devoted her life to advancing equal social, economic, and political rights for blacks. She distinguished herself by creating lasting institutions that trained black women for visible and expanding public leadership roles. Few have been as effective in the development of women's leadership for group advancement. Despite her accomplishments, the means, techniques, and actions Bethune employed in fighting for equality have been widely misinterpreted.

Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women's Political Activism seeks to remedy the misconceptions surrounding this important political figure. Joyce A. Hanson shows that the choices Bethune made often appear contradictory, unless one understands that she was a transitional figure with one foot in the nineteenth century and the other in the twentieth. Bethune, who lived from 1875 to 1955, struggled to reconcile her nineteenth-century notions of women's moral superiority with the changing political realities of the twentieth century. She used two conceptually distinct levels of activism—one nonconfrontational and designed to slowly undermine systemic racism, the other openly confrontational and designed to challenge the most overt discrimination—in her efforts to achieve equality.

Hanson uses a wide range of never- or little-used primary sources and adds a significant dimension to the historical discussion of black women's organizations by such scholars as Elsa Barkley Brown, Sharon Harley, and Rosalyn Terborg-Penn. The book extends the current debate about black women's political activism in recent work by Stephanie Shaw, Evelyn Brooks-Higginbotham, and Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore.

Examining the historical evolution of African American women's activism in the critical period between 1920 and 1950, a time previously characterized as "doldrums" for both feminist and civil rights activity, Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women's Political Activism is important for understanding the centrality of black women to the political fight for social, economic, and racial justice.

Examining the historical evolution of African American women's activism in the critical period between 1920 and 1950, a time previously characterized as "doldrums" for both feminist and civil rights activity, Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women's Political Activism is important for understanding the centrality of black women to the political fight for social, economic, and racial justice.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Publisher

University of MissouriYear

2003Print ISBN

9780826221544, 9780826214515eBook ISBN

97808262640461

The Making of a Race Woman

Mary Jane McLeod Bethune emerged from humble beginnings to become a leader of her race. Born on July 10, 1875, in Mayesville, Sumter County, South Carolina, she was the fifteenth in a family of seventeen children. In terms of wealth and education, the McLeod family was typical of many black families in the post–Civil War period: illiterate and poor. Despite the best efforts of the Freedman’s Bureau, northern missionary associations, and the freed people themselves, illiteracy remained widespread among black South Carolinians. In 1880, the illiteracy rate was 78.5 percent for all blacks ages ten and over, compared to 21.9 percent for whites. In raw numbers, four times as many blacks as whites lived below the poverty line, and four and a half times more blacks were imprisoned than whites.

Sumter County was characteristic of many rural counties in the post–Civil War South. In 1870, Sumter County was home to 25,268 residents; slightly more than 40 percent (10,211) of all persons over the age of ten could not read. Of the 7,463 whites living in the county, about 14 percent (1,012) of those over the age of ten could not write and only 9 percent (672) were attending school. The county statistics for African Americans were even worse. Of the 17,805 black residents, about 57 percent (10,110) over the age of ten could not write and only about 6 percent (1,079) were attending school. Economic indicators were equally dismal for blacks. In 1890, 68 percent of black South Carolinians worked in agricultural occupations, a figure that fluctuated little until the end of the 1930s. In 1880, about 80 percent (3,348) of Sumter County’s 4,167 farms were smaller than one hundred acres. Only about 38 percent (1,563) of landowners farmed their own land; about 49 percent (2,052) rented their farms for cash payments; about 13 percent (552) were sharecroppers. In 1870, the average farm income in the county was $847 per year, but regular economic cycles and the declining price of cotton dropped income levels to $347 per year by 1879. Ten years later, average income had risen to only $462 per year. In a county where most farmers made their living by raising livestock, Indian corn, and cotton, the small size of farm holdings and the large number of tenant farmers and sharecroppers were barriers to economic advancement. Since African Americans constituted about 70 percent of the county’s population, they represented the majority of poor farmers in the area.1

In Sumter County, as in many areas of the rural South, a small white minority controlled the social, political, and economic life of the poor, illiterate black majority, who survived on their meager earnings as small landowners, sharecroppers, and tenant farmers. The McLeods were one of these families, but family dynamics, religious convictions, and community standing made them atypical.

Family experience was one important factor in the formation of Mary McLeod Bethune’s worldview. However, her distinctive opportunities, her teachers, her mentors, the worsening racial climate in post-Reconstruction America, and the ideology of Victorian womanhood also played significant roles in her developing ideas on race and gender.

Only a few main sources give insight into Bethune’s early life: an incomplete, unpublished autobiography, a partial biography, and two oral history interviews. Pieced together between 1927 and her death in 1955, these sources are more an account of how Bethune remembered or reconstructed her past than of how she lived it. Taken together, they are a story of triumph meant to impart her wisdom to others. Bethune makes this clear in personal correspondence when she expresses her reasons for dedicating her home as the Mary McLeod Bethune Foundation: the foundation was to be a “Shrine” where the files about her life would be kept and a “place of research and contact for those who may come after me.”2 These few lines are instrumental in understanding Bethune’s assessment of her life and legacy, as the word “shrine” implies. Perhaps she saw herself as a saintly soldier in a war against racial injustice, or a key role model, but it is certain that she saw racial injustice as a long-term problem and believed others would be interested in studying the ways she fought to undermine all forms of segregation, overcome discrimination, and end racial prejudice. Clearly, Bethune left behind these sources to fashion her identity, highlight her public achievements, and justify her choices. Since we have little corroborating evidence about her early life, what follows is less a biographical account than a collection of recalled incidents that Bethune used to explain her lifelong work for the race.

The declining status of African Americans in the post-Reconstruction South had a profound impact on Bethune’s views of race relations. During the time she came of age, conservative whites, encouraged by their notions of black racial inferiority, used first custom and then law to force freed people back into positions of social, economic, and political dependence.3 Historian Guion Griffis Johnson has argued that southern white attitudes toward former slaves could be classified into five paternalistic concepts: modified equalitarianism; benevolent paternalism; separate but equal; separate and permanently unequal; and permanently unequal under paternal supervision. Johnson asserts that the majority of southern whites believed most strongly in categories four and five, which were most unfavorable to blacks. He further contends that most southern whites believed that black progress within the confines of the black race would be limited because of blacks’ uncivilized African heritage and accepted the premise of permanent inferiority for African Americans. Johnson maintains that these southern paternalists were politically powerful men who used “the fear of ignorant whites as a weapon of control over the lower classes of both races.”4

One by one, lawmakers in the states of the old Confederacy altered state constitutions written during Reconstruction to reflect these ideas and institutionalized a barrage of discriminatory laws that legally separated the races and assigned an inferior social, economic, and political status to blacks. The legal separation of blacks and whites began on trains in 1887 and rapidly spread to every imaginable place where blacks and whites might come together. By 1900, thoroughgoing legal segregation was commonplace. Economically, white landowners fostered black dependence by manipulating sharecropping systems, originally conceived as a compromise between white landowners and black agricultural workers, to keep African American farmers landless and dependent. Soon, black tenant farmers and sharecroppers found themselves trapped in a debt-peonage system as prices for cotton crops declined and landowners and merchants conspired to set high prices and interest rates for farm supplies in the cash-poor southern agricultural economy. Political avenues of redress closed for African Americans as literacy tests, “understanding” and grandfather clauses, poll taxes, and white primaries disfranchised the majority of black voters.5

In addition to legal constrictions, mobs used organized violence and systematic intimidation as an extralegal means to keep African Americans “in their place.” Conservative white southerners reinstated “home rule”—most often through violent means. In the post-Reconstruction South, violence against blacks became common, and lynching became its most visible image. In the last sixteen years of the nineteenth century, about twenty-five hundred lynchings took place. Between 1900 and 1914, approximately eleven hundred more people lost their lives to extralegal violence. Almost 96 percent of all lynchings in the United States occurred in the South, and the vast majority of these acts targeted blacks.6 Although most of the victims were black men, black women were not immune to the rampant violence as nineteenth-century ideas of gender excluded black women. In 1872, an unnamed black woman testified before the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Conditions of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States about her experience with the Ku Klux Klan: “They whipped me from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet. I was just raw. The blood oozed through my frock and all around the waist. After I got away from them that night I ran to my house. My house was torn down. I went in and felt where my bed was. I went to the other corner of the house and felt for my little children and I could not see them. Their father lay out to the middle of the night and my children lay out there too.”7 Simple statistics cannot convey the sense of terror blacks lived under in the post-Reconstruction South. Although federal actions worked to force the Klan to disband officially in 1872, white supremacist vigilantes continued to use terrorist tactics against a select group of black men, women, and children.

In 1887, at the age of twelve, Bethune witnessed this type of mob violence firsthand in an experience that influenced her interactions with whites. On a trip into town on market day, Bethune saw a white mob attack “Marse Eli Cooper’s Gus” because he refused to blow out a match for a white man and then in his anger knocked the man to the ground. In “bewildered terror,” young Mary saw the mob put a rope around Gus’s neck and heard her father’s command not to look back as he pulled her from the chaotic scene. Despite Samuel’s warning, she watched the event unfold. She saw “Marse Eli, the sheriff and other calm men of authority” arrive at the scene. They “stopped the hanging after the rope had been tightened around Gus’ neck.” Decades later Bethune remembered the “solemnity and fear” among blacks in Mayesville for several days after the incident.8 The immediate fear this episode invoked was only a short-term consequence of the experience for Bethune, however. The experience became a pivotal event in determining the nature of her interactions with whites. Throughout her lifetime, she remembered those “calm men of authority” and formed alliances with them, trusting that they would work with her to help end legal segregation.

Throughout the South in the post-Reconstruction era, white landowners, merchants, and businessmen often did not condone lynching, but generally did nothing to stop it. At certain times and under certain circumstances, however, upper-class whites interceded, most often because of their dependence on black labor. According to historian Leon Litwack, some whites expressed concern about the migration of black labor out of their state. Others expressed concern because they feared mob violence was a sign their region was descending into “barbarism.” Vigilante violence fed a “spirit of anarchy,” and was a sign that the “entire social order might be in jeopardy.” Many worried about the impact of such actions on the “economic well being of the New South.” Landowners and merchants considered blacks a valuable economic asset, and believed “It is not good business to kill them.” This was especially true in South Carolina, where African Americans comprised 68 percent of the agricultural workforce. In Sumter County, upper-class whites played the role of protector toward blacks to win their loyalty. Random acts of terror would severely disrupt the social and economic systems by which this small number of powerful whites profited. An occasional show of upper-class white protection was a part of a wider scheme of white control, and a few selected interventions of this nature reaped a high return for those whites involved. However, these interventions were not common. As historian Allen Trelease has argued, “It has been the accepted view that wealthy, cultured whites, including larger ex-slaveholders, cherished a kindlier feeling toward Negroes and exhibited less race hatred than their lower-class brethren. Close investigation, however, uncovers so many exceptions that the truth or usefulness of the belief is open to question.”9 Yet, this one violent incident witnessed by Bethune firmly planted in her mind the idea that upper-class whites were potential protectors. This lack of introspection had implications for the future. Bethune often relied on men and women of this class for financial and political help in undermining segregation, with few positive effects. Moreover, she then found herself struggling to limit white paternalism. This becomes clear in two events explored further in later chapters: the founding of Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls in 1904, when she would depend on the financial support of white philanthropists and their wives, and during her government service, when she would look to white racial liberals for political support in her work as director of Minority Affairs in the New Deal administration.

By the turn of the twentieth century, conservative whites had effectively constricted black social space, limited economic opportunities, and undermined black political participation in the South. However, vigilante mobs worked to silence many fair-minded southern whites as well. White supporters of black rights often risked attacks on their homes and families. This was a possibility many racial liberals in the New South sought to avoid. In the post-Reconstruction era, African Americans struggled under the shadow of vigilante violence and without legal protection to maintain family and community ties, and looked to each other for social relationships, to promote economic development, and to address political concerns.

African Americans endured horrific conditions in the South, but anti-black sentiments were not restricted to the region, or to white mobs. Academics and intellectuals nationwide played an important role in fostering anti-black beliefs. White Americans increasingly perceived “race purity” as a national problem as expanding numbers of southern and eastern European immigrants migrated to America after 1880. This quest to maintain “race purity” intensified again as increasing numbers of blacks moved from the rural South to the urban North during the first decades of the twentieth century. Social Darwinism and new pseudo-scientific biological evidence allegedly “proved” that African Americans as well as other ethnic minorities were innately and irreversibly inferior to whites. In 1916 Madison Grant, chairman of the New York Zoological Society, warned in The Passing of the Great Race that America had become “an asylum for the oppressed.” A new wave of immigration contained “a large and increasing number of the weak, the broken, and the mentally crippled races.” According to Grant, these “lower races” were incapable of understanding American ideals; their incorporation into American society would only serve to “mongrelize” the white race.10 Grant’s work reinforced stereotypes and gave proponents of the eugenics movement an academic basis to advocate the sterilization of these “lower races” to ensure the purity and superiority of the white race.

Cultural media also avowed the inferiority of these new immigrants and African Americans. Books such as Henry James’s The American Scene, Edward Ross’s The Old World in the New, Charles Carroll’s The Negro a Beast, Robert W. Shufeldt’s The Negro: A Menace to American Civilization, and Thomas Dixon’s trilogy As to the Leopard’s Spots, The Clansman, and The Traitor gained large audiences. Dixon, however, wanted his work to reach a much larger audience. He saw a new medium, the motion picture, as the means to reach and influence millions of people. After several unsuccessful attempts to find a producer, he approached D. W. Griffith and convinced him to transform The Clansman into an epic motion picture. The result, Birth of a Nation, undoubtedly became the most significant factor in perpetuating black stereotypes, glorifying the Ku Klux Klan, and condoning racial violence. Moreover, after a private screening, President Woodrow Wilson’s remark that the film was entirely accurate history served to intensify anti-black hatred and violence.11

Leadership changes in the black community also contributed to changing patterns of race relations, and these changes influenced Bethune’s developing racial philosophy. The emergence of Booker T. Washington following the death of Frederick Douglass in 1895 encouraged a new era of accommodation in race relations. Washington urged that African Americans accept the formal disfranchisement whites imposed upon them and improve their economic standing by means of industrial education and hard work. He told African Americans, “all forms of labor are honorable, and all forms of idleness disgraceful. It has been necessary . . . to learn that all races that have gotten to their feet have done so largely by laying an economic foundation, and, in general, by beginning in a proper cultivation and ownership of the soil.”12

Washington encouraged African Americans to “cast down your bucket where you are,” to make a new beginning wherever possible. For most blacks in the South, this meant work in agriculture, mechanics, and domestic service. According to Washington, the greatest need for the black man was t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. The Making of a Race Woman

- 2. Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for Negro Girls

- 3. Mutual Aid, Self-Improvement, and Social Justice

- 4. In the National Youth Administration

- 5. The National Council of Negro Women

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women's Political Activism by Joyce A. Hanson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.