![]()

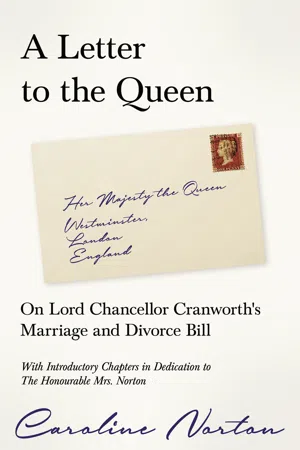

Madam,

On Tuesday, June 13th, of last session, Lord Chancellor Cranworth brought forward a measure for the reform of the Marriage laws of England; which measure was afterwards withdrawn. In March, 1855, in this present session, the Solicitor General stated, that a bill on the same subject was "nearly prepared," and would be brought forward "immediately after the Easter recess." On May 10th, being pressed to name a time, he stated that it would be proposed "as soon as the House had expressed an opinion on the Testamentary Jurisdiction Bill." That time has not arrived: and meanwhile,–as one who has grievously suffered, and is still suffering, under the present imperfect state of the law,–I address your Majesty on the subject.

I do not do so in the way of appeal. The vague romance of "carrying my wrongs to the foot of the throne," forms no part of my intention: for I know the throne is powerless to redress them. I know those pleasant tales of an earlier and simpler time, when oppressed subjects travelled to the presence of some glorious prince or princess, who instantly set their affairs to rights without reference to law, are quaint old histories, or fairy fables, fit only for the amusement of children.

I connect your Majesty's name with these pages from a different motive; for two reasons: of which one, indeed, is a sequence to the other. First, because I desire to point out the grotesque anomaly which ordains that married women shall be "non-existent" in a country governed by a female Sovereign; and secondly, because, whatever measure for the reform of these statutes may be proposed, it cannot become "the law of the land" without your Majesty's assent and sign manual. In England there is no Salique law. If there were,–if the principles which guide all legislation for the inferior sex in this country, were carried out in their integrity as far as the throne,–your Majesty would be by birth a subject, and Hanover and England would be still under one King.

It is not so. Your Majesty is Queen of England; Head of the Church; Head of the Law; Ruler of millions of men; and the assembled Senate who meet to debate and frame legislative enactments in each succeeding year, begin their sessional labours by reverently listening to that clear woman's voice,–rebellion against whose command is treason.

In the year 1845, on the occasion of the opening of the new Hall of Lincoln's Inn, your Majesty honoured that Hall with your presence: when His Royal Highness Prince Albert was invited to become a Barrister: "the keeping of his terms and exercises, and the payment of all fees and expenses, being dispensed with." It was an occasion of great pomp and rejoicing. No reigning sovereign had visited the Inns of Court since Charles II., in 1671. In the magnificent library of Lincoln's Inn, seated on a chair of state (Prince Albert standing), your Majesty held a levee; and received an address from the benchers, barristers, and students-at-law, which was read by the treasurer on his knee: thanking your Majesty for the proof given by your presence of your "gracious regard for the profession of the law,"–offering congratulations "on the great amendments of the law, effected since your Majesty's accession;" and affirming that "the pure glory of those labours must be dear to your Majesty's heart."

To that address your Majesty was graciously pleased to return a suitable answer; adding,–

"I gladly testify my respect for the profession of the law; by which I am aided in administering JUSTICE, and in maintaining the prerogative of the Crown and the rights of my people."

A banquet followed. The health of the new barrister, the Prince Consort, was drunk with loud cheers. His Royal Highness put on a student's gown, over his Field Marshal's uniform, and so wore it on returning from the Hall; and then that glittering courtly vision–of a young beloved queen, with ladies in waiting, and attendant officers of state, and dignitaries in rich dresses, melted out of the solemn library; and left the dingy law courts once more to the dull quiet, which had been undisturbed by such a glorious sight for nearly two hundred years. Only, on the grand day of the following Trinity term, the new Barrister, His Royal Highness Prince Albert, dined in the Hall as a Bencher, in compliment to those who had elected him.

Now this was not a great mockery; but a great ceremony. It was entered into with the serious loyalty of faithful subjects: with the enthusiasm of attached hearts: and I know not what sight could be more graceful or touching, than the homage of those venerable and learned men to their young female sovereign. The image of Lawful Power, coming in such fragile person, to meet them on that vantage ground of Justice, where students are taught, by sublime theories, how Right can be defended against Might, the poor against the rich, the weak against the strong, in their legal practice; and how entirely the civilised intelligence of the nineteenth century rejects, as barbarous, those bandit rules of old, based on the "simple plan,"

"That they should take, who have the power,

And they should keep, who can."

It was the very poetry of allegiance, when the Lord Chancellor and the other great law officers did obeisance in that Hall to their Queen; and the Treasurer knelt at a woman's feet, to read of the amendments in that great stern science by which governments themselves are governed; whose thrall all nations submit to; whose value even the savage acknowledges,–and checks by its means the wild liberty he enjoys, with some rude form of polity and order.

Madam,–I will not do your Majesty the injustice of supposing, that the very different aspect the law wears in England for the female sovereign and the female subject, must render you indifferent to what those subjects may suffer; or what reform may be proposed, in the rules more immediately affecting them. I therefore submit a brief and familiar exposition of the laws relating to women,–as taught and practised in those Inns of Court, where your Majesty received homage, and Prince Albert was elected a Bencher.

* * * * *

A married woman in England has no legal existence: her being is absorbed in that of her husband. Years of separation of desertion cannot alter this position. Unless divorced by special enactment in the House of Lords, the legal fiction holds her to be "one" with her husband, even though she may never see or hear of him.

She has no possessions, unless by special settlement; her property is his property. Lord Ellenborough mentions a case in which a sailor bequeathed "all he was worth" to a woman he cohabited with; and afterwards married, in the West Indies, a woman of considerable fortune. At this man's death it was held,–notwithstanding the hardship of the case,–that the will swept away from his widow, in favour of his mistress, every shilling of the property. It is now provided that a will shall be revoked by marriage: but the claim of the husband to all that is his wife's exists in full force. An English wife has no legal right even to her clothes or ornaments; her husband may take them and sell them if he pleases, even though they be the gifts of relatives or friends, or bought before marriage.

An English wife cannot make a will. She may have children or kindred whom she may earnestly desire to benefit;–she may be separated from her husband, who may be living with a mistress; no matter: the law gives what she has to him, and no will she could make would be valid.

An English wife cannot legally claim her own earnings. Whether wages for manual labour, or payment for intellectual exertion, whether she weed potatoes, or keep a school, her salary is the husband's; and he could compel a second payment, and treat the first as void, if paid to the wife without his sanction.

An English wife may not leave her husband's house. Not only can he sue her for "restitution of conjugal rights," but he has a right to enter the house of any friend or relation with whom she may take refuge, and who may "harbour her,"–as it is termed,–and carry her away by force, with or without the aid of the police.

If the wife sue for separation for cruelty, it must be "cruelty that endangers life or limb," and if she has once forgiven, or, in legal phrase, "condoned" his offences, she cannot plead them; though her past forgiveness only proves that she endured as long as endurance was possible.

If her husband take proceedings for a divorce, she is not, in the first instance, allowed to defend herself. She has no means of proving the falsehood of his allegations. She is not represented by attorney, nor permitted to be considered a party to the suit between him and her supposed lover, for "damages." Lord Brougham affirmed in the House of Lords:

"in that action the character of the woman was at immediate issue, although she was not prosecuted. The consequence not unfrequently was, that the character of a woman was sworn away; instances were known in which, by collusion between the husband and a pretended paramour, the character of the wife has been destroyed. All this could take place, and yet the wife had no defence; she was excluded from Westminster-hall, and behind her back, by the principles of our jurisprudence, her character was tried between her husband and the man called her paramour. "

If an English wife be guilty of infidelity, her husband can divorce her so as to marry again; but she cannot divorce the husband a vinculo, however profligate he may be. No law court can divorce in England. A special Act of Parliament annulling the marriage, is passed for each case. The House of Lords grants this almost as a matter of course to the husband, but not to the wife. In only four instances (two of which were cases of incest), has the wife obtained a divorce to marry again.

She cannot prosecute for a libel. Her husband must prosecute; and in cases of enmity and separation, of course she is without a remedy.

She cannot sign a lease, or transact responsible business.

She cannot claim support, as a matter of personal right, from her husband. The general belief and nominal rule is, that her husband is "bound to maintain her." That is not the law. He is not bound to her. He is bound to his country; bound to see that she does not cumber the parish in which she resides. If it be proved that means sufficient are at her disposal, from relatives or friends, her husband is quit of his obligation, and need not contribute a farthing: even if he have deserted her; or be in receipt of money which is hers by inheritance.

She cannot bind her husband by any agreement, except through a third party. A contract formally drawn out by a lawyer,–witnessed, and signed by her husband,– is void in law; and he can evade payment of an income so assured, by the legal quibble that "a man cannot contract with his own wife."

Separation from her husband by consent, or for his ill usage, does not alter their mutual relation. He retains the right to divorce her after separation,–as before,–though he himself be unfaithful.

Her being, on the other hand, of spotless character, and without reproach, gives her no advantage in law. She may have withdrawn from his roof knowing that he lives with "his faithful housekeeper": having suffered personal violence at his hands; having "condoned" much, and being able to prove it by unimpeachable testimony: or he may have shut the doors of her house against her: all this is quite immaterial: the law takes no cognisance of which is to blame. As her husband, he has a right to all that is hers: as his wife, she has no right to anything that is his. As her husband, he may div...