This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Professor Speidel's book represents the first history of the Roman horse guard ever written and provides a readable account of the intricate part these men played in the fate of the Roman empire and its emperors.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Riding for Caesar by Micheal P. Speidel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

FROM CAESAR TO NERO

Picked auxiliary horsemen, called Batavi after the island in the Rhine, the finest horseback riders.

Dio 55, 24, 7.

Caesar’s Germani horsemen

By 52 BC, Caesar had brought the Gauls to their knees, yet in the winter of that year, under Vercingetorix, they rose in arms against him with such fury that all seemed lost. No sooner had Caesar brought his legions together than the vanguard of the Gaulish horse bore down on him at the town of Noviodunum. Drawing up his regular cavalry in battle line, Caesar sent it to meet the Gauls. Before long his men began to waiver. At that critical moment, when all was at stake, Caesar threw his Germani into the fray—‘some four hundred horsemen he had with him from the beginning’. The Gauls, unable to withstand their onslaught, broke and fled. Caesar’s horse guard thus saved him from being trapped in certain defeat.

Holding back reserves until the decisive moment, Caesar had won by tactical skill. It is nevertheless astonishing that only four hundred men made such a difference. They must have been the kind of men Caesar’s own army feared, ‘huge, unbelievably bold and expert fighters’. Perhaps they attacked at a risky full gallop. Were they regular troops of the line or a guard? Caesar, saying that he had them ‘with him’, marks them as his escort, and his keeping them behind the battle line shows they were a reserve. As an escort and battlefield reserve, Caesar’s German horsemen clearly were his guard. The history of the Roman emperors’ horse guard thus begins at Noviodunum in Gaul in 52 BC.1

Where did Caesar hire these men? In 58, in the first year of the Gallic War, when he needed a trustworthy force to face the Suebian king Ariovistus and his horsemen at a parley, Caesar mounted the tenth legion on borrowed horses. Later that year he routed the Suebi and acquired German allies, the Ubians, who finished off the beaten Suebi. In 57, embassies from tribes east of the Rhine came with offers to join Caesar. Among them, no doubt, were Ubians whom he may have asked for horsemen since Roman field marshals, like Hellenistic dynasts, were wont to rely on foreign bodyguards. The Ubians ever after kept in touch with Caesar and, under the Julio-Claudian emperors, supplied more men to the emperor’s horse guard than any other tribe save the Batavians. Very likely, therefore, Ubians served already in Caesar’s guard.2

In 49 BC, when Caesar hastened to war in Spain, 900 horsemen rode with him, surely his German horse guard as well as Gaulish horsemen. After the battle of Pharsalus in 48 he took 800 horsemen of the guard along to Egypt, among them also Gauls. Caesar used the Gauls in his assault on Pharos island. Later, when he broke the siege at Alexandria —sweetened by Cleopatra—and faced the Egyptian army across the Nile, his German horsemen showed their mettle. They scattered and rode into the river to find fords for the legions. Where the banks were less steep, they swam across, established bridgeheads and routed the enemy, thereby allowing the legions to cross. Since Batavians later made up the bulk of the horse guard, and since they excelled in swimming rivers in full battle gear, Caesar’s equites Germani on the Nile, too, may have been Batavians.

From Egypt, Caesar went to Asia, and on to Rome, traveling at great speed ‘with horsemen in light order’—clearly his guard. Escort duty with Caesar was not for laggards. Keen horseman that he was, he dashed from one theater of war to another and demanded of his soldiers instant readiness, in any weather, at any time, day or night. He himself swam across rivers that would otherwise have hindered his lightning travels of up to a hundred miles a day. His guard had to ride as fast and swim as well.3

In the African war of 46, Caesar again had his German horsemen with him. When he faced Labienus, he found that his former second-in-command, now his opponent, also had a guard of Gaulish and German horsemen. Some of these were men of Caesar’s army who had come to Africa with Curio in 48 BC. Spared after Curio’s defeat, they had joined the Pompeians; now they made a truce with Caesar’s guardsmen to see how they could avoid fighting each other. Labienus’ horsemen, however, like Caesar’s, balked at betraying their trust, and the talks broke off. Afterwards, in battle, Labienus’ other cavalry fled, but his Gaulish and German horsemen stood their ground. Attacked from above, and set upon in the rear, they were killed to a man. When the dead had been stripped, Caesar, going over the body-strewn field, was awed by their huge build and by the fact that, having been spared before, they wanted to return that favor by keeping faith with the Pompeians to the last. The German ideal of being ‘true’—to repay favours with faith—was the same as the Roman ideal of fides.

The ‘wonderful bodies’ (mirifica corpora) that astounded Caesar are highlighted by a relief on the victory monument at Adamklissi. There, two warriors of staggering size are guarding Trajan who leans against a tree, the staff of command under his arm, as he watches a battle in the wooded hills of Dacia. No horses are shown but they must be nearby, for in the field the emperor always rode on horseback. The two warriors, therefore, are likely to be Batavi horsemen of Trajan’s bodyguard. The geographer Strabo likewise saw Germans as larger and fiercer than Gauls, with redder hair.

From the anonymous author of the African War we learn that Caesar had raised his horsemen ‘by influence, money, and promises’ (auctoritate, pretio, et pollicitationibus). Caesar’s influence may have brought him Gauls; money and promises brought him Germans. Promises must have meant cash awards once the wars were over. The wars never ended, but from here, surely, dates the custom that the emperor’s horsemen, unlike other auxiliaries, could look forward to cash awards (commoda) upon discharge—which made them partners in the emperor’s undertakings.

Labienus swelled the number of his Gaulish and German horsemen not only with prisoners of war, but also with half-breeds, freedmen, and slaves—all sorts of beholden men. This source of recruits for the guard was never wholly given up, and indeed some of Tiberius’ guardsmen were former slaves. Slander made this a stain on the guard: Caracalla was rumored to have bought slaves in Germany for his Lions, and Galerius was said to have raised his horse guard from prisoners of war.

We are not told whether Caesar took his German horsemen on the last of his campaigns, the Spanish war of 45. Yet since he had taken them to all the other battlefields of the Civil War, and since he always needed a guard of fighting men, they are bound to have gone along, racing as best they could over the 2400 km (1500 miles) from Rome to Cordova in just 25 days, an average speed of 90 km (55 miles) a day. As for Caesar, he must have traveled in a carriage, for he found time to describe the journey in verses. No poems are likely to have been written by his horsemen during those 25 days, and most of them lagged behind: upon arrival Caesar found himself in want of a horse guard.4

Back in Rome, three months before he was murdered, Caesar took a pleasure trip to Campania, visiting Cicero in his villa at Puteoli. In a letter to a friend, Cicero frets that his villa was overrun by soldiers, nearly 2000 of them! The units to which these soldiers belonged are not known, but since Caesar never mentions a praetorian guard and probably had none, and since he traveled on horseback, some of the soldiers, surely, belonged to his horse guard. Later, passing the house of Dolabella, Caesar honored the Consul-elect by having his men parade to the left and the right of his horse—the first time we see the horse guard in its role of lending luster to the sight of a Roman ruler.

Caesar’s German horsemen had served well as a crack battlefield unit and an escort. Shortly before the Ides of March in 44 BC he made them his sole bodyguard, dismissing his former Spanish guard. The Spaniards were armed mainly with swords and thus were not primarily horsemen. Although they had been utterly faithful, in the planned Parthian War Caesar needed first-class horsemen around him wherever he went. Augustus later likewise used his German horsemen as bodyguards, calling them Germani corporis custodes.

Caesar thus was the founder of the emperors’ horse guard. Having carried the Roman frontier to the Rhine, he recruited his guard from the tribes there, setting the pattern for two hundred years to come. By forging the horse guard into an efficient fighting force, reading to ride with the ruler across the length and breadth of the empire, he laid one of the foundations of the new monarchy. The guard’s tireless speed, its willingness to fight, and its trustworthiness never failed him. Its far-flung journeys in Caesar’s service (Fig. 1) breathe a dogged steadfastness that matched the pace of the Genius and the vastness of the empire.5

Fig.1. The journeys of Caesar’s horse guard (52–45 B.C.)

Augustus’ horse guard

After Caesar’s death, his German horsemen sided with Octavian. In 43 BC they went over to Mark Antony, but so did Octavian, and both leaders of the Caesarian forces had German horsemen with them at the battle of Philippi in 42. Afterwards Mark Antony took some of them with him to the Orient, but Octavian, too, during his campaign in Sicily in 36, had a Germani guard, very likely the same men as Caesar’s, for he would not have sent home battle-tried guardsmen only to ask, not much later, for new and untried troopers. To be sure, losses had to be made up, and veterans had to be replaced by recruits, but there is little doubt that the same unit guarded Caesar and Augustus. As under the later Julio-Claudian emperors, the troopers seem to have been Batavians and Ubians. Their service in the emperor’s guard would explain why both tribes were admitted to the Roman side of the Rhine, the Ubians as early as 38 BC, ‘for having proven their trustworthiness’—surely in the horse guard.6

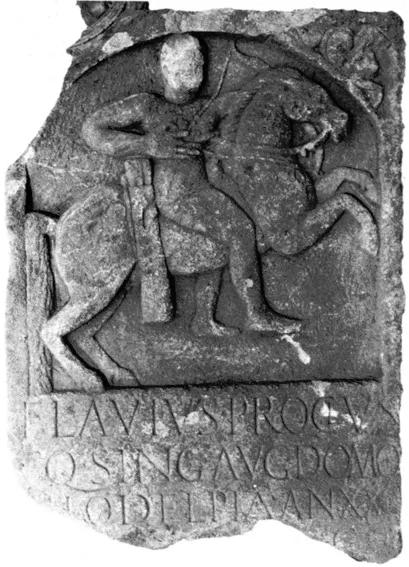

1 Gravestone of Flavius Proclus, found at Mainz, Germany. Proclus, Arab archer of the horse guard, draws a composite bow, pulling the string with his middle and index fingers in the ‘western release’ towards his chest.

Whether Augustus’ bodyguards were all horsemen is not known, though the fact that they are called Batavi, like the third-century horse guard, suggests that they were. The emperor chose Batavians not for being foreigners, but for being the finest horsemen anywhere. His legate in Lower Germany no doubt picked them from tribal warriors who as allies had proven their horsemanship and fighting skill.

Our sources seldom mention Augustus’ horse guard, since he, unlike his successors, wanted to keep so monarchical an institution in the background. In a sense, it was because of the guard that he had to forego the title Romulus he craved. Livy, whom Augustus called a Pompeian because of his political outspokenness, pointedly tells that Romulus was beloved ‘more by the soldiers than by the senate’, for ‘he kept 300 armed Celeres [‘Swift’]-horsemen about him as a guard, not only in war but also in peace’. Indeed, Livy was not above broadcasting the wicked whisper that the senators had torn Romulus to pieces for being a tyrant.

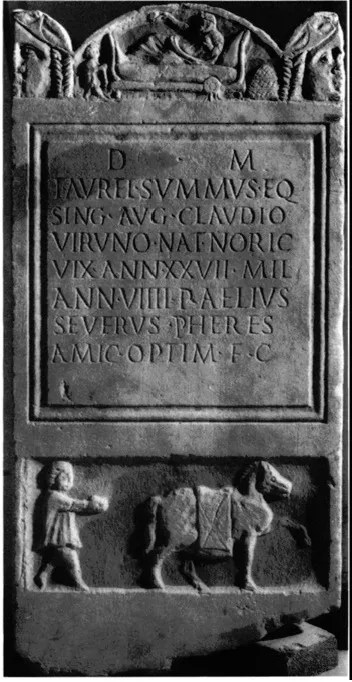

2 Gravestone of a horse guardsman, Rome. The funeral banquet and the groom, long-reining the horse, are motifs brought from Lower Germany.

Since archaic Greek times, so history told, tyrants had used their bodyguards to oppress the free, witness Peisistratos in Athens and Pausanias in Sparta. Caesar had claimed to be a new Romulus, and now when Octavian, too, wanted to be Romulus, Caesar’s bloodied ghost stirred again. To avoid his adopted father’s fate, Octavian had to settle for the title Augustus—all because of Romulus’ horse guard. The bodyguard must have made Caesar and Augustus look like tyrants. Cicero’s grumbling that Caesar came on a visit with 2000 armed men shows that by its numbers alone the guard overwhelmed even the most high-flying citizen.7

History had changed. Rome had become an empire, and the days of the citizen foot soldier drew to an end. Horsemen first held sway on battlefields in about 1000 BC in Assyria. From that time on, horse guards, elite household troops of the rulers, often 1000 strong, played a key role in the empires that followed one another. Sargon of Assyria in 714 BC boasted:

With one thousand fierce horsemen, bearers of bow, shield, and lance, my brave warriors, trained for battle, who never leave me, either in a hostile or in a friendly land, I set out and took the field.

The Persian emperors likewise took to the field with 1000 picked horsemen, and so did the Seleucid kings in Syria as well as the Ptolemies in Egypt. Alexander, like Septimius Severus, had 2000 horse guardsmen, for to him they were a first-strike force. With the rise of the great marshals of the Late Republic, Rome fell into this pattern.

Unable to hide the empire’s need for a ruler and the ruler’s need for a guard, Augustus could claim, at least, that the fine state of the army, the long peace, and his own high standing freed him from the need to fawn upon the soldiers. He showed this by placing the fort of the horse guard north of the Tiber, far from the Forum and the Senate Hall (see Fig. ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Plates

- Maps and Drawings

- Acknowledgements

- Picture Credits

- Foreword

- 1. From Caesar to Nero

- 2. Riding High: The Second Century

- 3. The Roughshod Third Century

- 4. Tall and Handsome Horsemen

- 5. Aristocratic Officers

- 6. Weapons and Warfare

- 7. Life In Rome

- 8. Gods and Graves

- 9. Training Faithful Frontier Armies

- 10. Death At the Milvian Bridge

- Conclusion

- Time Chart

- Glossary

- Further Reading

- Notes

- Bibliography