1

INTRODUCTION

General introduction

The long-distance trade in silk, spices and incense which was a feature of the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire has long attracted attention, both from scholars and in more popular literature. This is perhaps not surprising, as the images of camel caravans laden with silk and spices, fabulously rich ‘caravan cities’ and ships making the long and dangerous journey from the Red Sea to India and back in search of Indian pepper and other goods have often excited the imagination of scholar and lay reader alike. Indeed, a number of general studies of the eastern trade of the Roman Empire have already been made, which might bring one to question the need for this work.

Many of the studies of the trade completed earlier in the twentieth century, however, place great emphasis on a view of a strongly proactive Roman policy toward the trade. Indeed, many more recent writers have followed this tendency as well. These views have put forward such ideas that the Romans tried to promote or encourage the trade, and especially to force non-Roman ‘middlemen’ out of the trade and to concentrate the trade into Roman hands.1 Such policies are envisaged as proceeding from the highest levels of government: on many occasions, commercial motives of this type have been posited as explanations for major military initiatives in the East, such as the annexation of the Nabataean kingdom in AD 106 or Trajan’s Parthian expeditions. In addition, Roman officials at both imperial and provincial levels are seen as deliberately encouraging the trade in some areas by the provision of facilities, or redirecting trade routes in order to weaken the commerce in other areas. One recent study, while retreating from such an extreme view of Roman involvement in the trade, has still suggested that the provision of facilities for the commerce is indicative of a direct imperial interest in the commerce and of a proactive trade policy proceeding from the imperial court.2

Such views, however, have not been left unchallenged. In one particularly significant work on the topic, M.G.Raschke has questioned many of the assumptions which have been made about the Roman commerce with the East.3 His reappraisal of the commerce has emphasised the fact that the ‘middlemen’ involved in the trade were usually Romans or Roman subjects, and consequently the views which emphasise attempts to remove non-Roman ‘middlemen’ should be rejected. Similarly, it has been shown that the vast majority of Roman foreign policy initiatives in the East can be better understood as stemming from military aggression and aggrandisement rather than from any economic motives.4 While emphasising this view of imperial policy, however, scant attention has been paid to the political influence of the trade at a lower level: that is, in the communities of the Roman East itself. Some work, indeed, has been done on the significance and political effect of the trade on the Nabataean kingdom and Palmyra,5 but this has generally been done against the background of the proactive view of Roman policy toward the trade. Even in the absence of any ‘trade policy’ from the imperial or provincial governments, however, we might expect to see local authorities acting to exploit and encourage the commerce through their own communities.

Accordingly, in the course of this work it is proposed to study closely the various routes and communities involved in the commerce, and the commodities in which the trade was carried on. This book will examine each individual area in which the eastern trade was active. First, the effect of the commerce on the actions of the Roman government will be examined, whether such actions come from the emperor, provincial governors or local authorities. After this, the significance of the trade to the relevant local communities will be examined by a study of the things which can be discovered about the people involved in the commerce, and the way in which local authorities acted toward the trade and its practitioners.

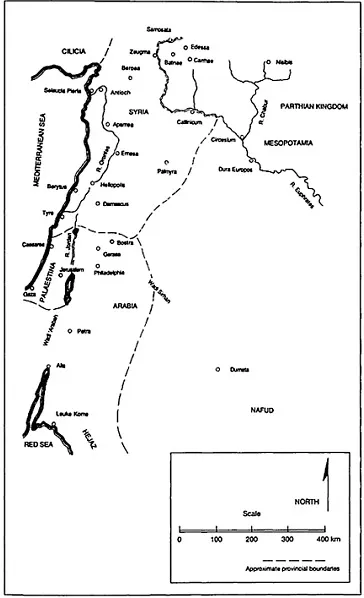

This work does not intend to be a comprehensive history of the eastern trade in the Roman East. Rather, it tries to collect and examine evidence for the existence of various trade routes coming into and passing through the Roman East, and their effect on Roman imperial policy in the area and on local political formations within the Roman eastern provinces. For the purposes of this study, the ‘East’ is defined as the territory covered by the provinces of Syria, Mesopotamia, Palaestina, Arabia and Egypt, as well as client kingdoms in this general area (see Map 1.1). The period of the study is roughly from the accession of Augustus in 31 BC to the abdication of Diocletian in AD 305. This period covers what we might call the ‘classical’ period of the Roman eastern trade, which really ended with the fall of Palmyra in AD 272. The extension of the period under study to AD 305 allows the examination of some of the effects of this fall, without going too far into the late Roman/Byzantine period, which saw a significant recovery of the trade as well as important changes in the government’s treatment of it, and therefore warrants its own separate study.

In the first chapter, the Introduction, some basic background essential to the study and understanding of the trade is set out. After this general introduction, the wide variety of source material which will be used in this study is briefly surveyed, followed by an overview of the trade within the Roman Empire, concentrating on the demand for eastern goods in Rome, the types of goods which were imported, and what can be known about the volume and general conduct of the trade within the empire.

Chapter 2 focuses on one of the best attested areas of the trade, Roman Egypt. First, the types and sources of the various goods of the Red Sea trade are studied, followed by an examination of the manner in which the trade goods were conveyed from the Red Sea coast through Egypt and then into Alexandria, before their shipment to the markets of the empire. After this, the various participants in the Egyptian trade are examined, both private individuals and government officials, and a likely motivation for the involvement of the Roman government in the trade is presented. Finally, changes which occurred to the trade over the course of the period under study are documented, and a series of conclusions about the trade in Egypt reached.

Map 1.1 The Roman Near East —showing the approximate boundaries of Roman provices as they were in AD 118–161, from the abandonment of Trajan’ Parthian conquests to the commement of Lucius Verus’ eastern campaign.

The same general outline is followed in Chapter 3, the study of the trade in Roman and pre-Roman Arabia. In this chapter, however, the study will be divided into two broad sections: that which deals with the trade in the Nabataean kingdom, and that which deals with the commerce in the Roman province of Arabia, which succeeded the Nabataean realm in AD 106. Particular emphasis will be given to ideas of a deliberate Roman weakening of the Nabataean kingdom and their relevance to Roman government policy with respect to the trade. Possible motives for the Roman annexation of the kingdom and the considerable military buildup which took place along the Arabian frontier after the Roman takeover will be considered.

A similar outline is once again followed in Chapter 4, which is devoted to the study of the commerce of Palmyra. Special attention, however, is given to the high degree of importance that the trade held in Palmyra and to some of the effects which the commerce may have had on Palmyra’s political organisation and society. While much of the information which we have dealing with the eastern trade in Syria comes from Palmyra, it is clear that some commerce passed through northern Syria and along the Euphrates river as well, bypassing Palmyra altogether. These routes form the subject matter of Chapter 5, which gives special attention to the matter of Roman relations with Parthia and the question of whether or not the eastern trade had any influence on these relations. Having then examined the eastern trade in all the major areas, Chapter 6 turns to an investigation of the imperial attitude toward the commerce, drawing on fresh evidence as well as that which has been covered in the regional studies. Attention is given to possible influences on the government attitude to the commerce, including on the one hand the Roman attitude toward luxuria and mollitia, two vices which the Romans saw as related to the use of luxury goods, and on the other hand the significant tax revenues which the government was able to extract from the commerce. Chapter 7 then forms a conclusion to the whole study, focusing on the nature of the trade, the effects of the trade on the imperial government and its policy in the East, and finally on the trade’s significance to political formations in the communities of the Roman East.

The Appendices mostly provide greater information on topics noted in the text. Appendix A lists prices for various commodities in the trade as listed in Pliny the Elder’s Historia Naturalis, and a brief comparison of these prices with the prices of staples and regular wages to give some idea of the relative expense of the items. Appendix B deals with the silver content of Nabataean coins, which is relevant to the question of whether or not the Nabataean kingdom experienced an economic slump in the first century AD, and whether or not this was related to the trade passing through the kingdom. Charts of Roman currencies over the same period are provided for comparison. Appendix C deals with those inscriptions which mention an independent Palmyrene military organisation in the years prior to the Palmyrene rebellion against Rome in the third century, while Appendix D describes the changes in Palmyra’s political situation from AD 251 to AD 267.

A note on the sources

The study of the long-distance trade of the Roman East cannot depend on only one or two historical sources, but must take into account a wide variety of literary, archaeological, epigraphic and other material. Indeed, there is no one pre-eminent source to which we can turn in this study. Instead, we are forced to rely on more or less peripheral comments in works devoted to other subjects: only in two cases, the Periplus Maris Erythraei and the Palmyrene corpus of caravan inscriptions, could we truly say that we have a primary source actually devoted to the subject in hand. Nonetheless, there is a wide variety of works which touch on the topic from time to time, although the scattered and diverse nature of the evidence warrants some caution.

Literary sources

As already mentioned, the Periplus Maris Erythraei is the only literary source which has the spice and silk trades as its primary subject. As a result, this merchant’s handbook for the Egyptian Red Sea trade is invaluable, providing not only copious information on the trade routes and ports of call in India, Africa and Arabia which Egyptian based ships used, but also lists of goods traded at each port. The very nature of this book also inspires confidence in the truth of its accounts: it is a workmanlike, practical manual for the merchant of the Red Sea trade, never intended as a work of literature, and thus we may reasonably expect the accounts it provides to be accurate.6

This view of the Periplus is strengthened still further when an examination is made to see what can be learned about its author. Although the writer does not name himself, the Periplus is apparently the work of a merchant with considerable first-hand experience of the trade, as is shown at several points in the text.7 By his references to Egyptian months and, at one point, his mention of ‘the trees we have in Egypt’,8 it is evident that he must have been a Greek-speaking resident of Egypt.9 It is clear then that his work was intended as a guide for other merchants like himself who intended to be involved in the Red Sea trade. Accordingly, the information it provides can probably be relied upon to reflect at least the view of the trade that an Egyptian merchant would have held at the time. In the absence of strong evidence to the contrary, it would seem reasonable to accept the Periplus’ accounts and descriptions at face value. Although its emphasis is on the Egyptian trade, it can also provide some interesting insights into the trade in Arabia and further afield.

There has, however, been a long-standing dispute over the date of composition of the work, which has some potential impact upon its reliability. Most scholars date the work to the middle of the first century, which would make it a primary source of great importance, as this was the time at which the Red Sea trade seems to have peaked. Others, however, have contended that the work dates from the third century, and is consequently of lesser importance in any study of the trade.10 The date would actually appear to be settled by a comment within the Periplus itself, which refers to a king at Petra named Malichus.11 As Nabataean chronology is now well established, we can be sure that Malchus II reigned in Petra AD 40–70, and therefore we can date the Periplus to the same period.12 Similarly, the Periplus’ reference to ‘Charibael, king of the Homerites and Sabaeans’13 has been identified as a Hellenised reference to the king Karib’il Watar Yuhan’im I, king of Saba and dhu-Raydan, who reigned in the first century AD and probably before AD 70.14 Some, however, would still try to put forward a later date, although their arguments have been effectively refuted by Dihle.15 On the whole, it seems eminently reasonable to allot the Periplus to the middle of the first century AD, and consequently to regard it as a first-hand source of pre-eminent importance for the study of the Egyptian Red Sea trade.

Other literary sources are more peripheral to the subject, but still often make useful references to the eastern long-distance trade. In this category the ancient geographers are of particular im...