I. | Hermeneutical Preface to Reading Kant |

THE CRITIQUE OF Pure Reason is one of the pivotal texts in the history of metaphysics. Our task is to begin reading that text.

To read such a text, however, is anything but a straightforward affair. In light of the work of Heidegger, Gadamer, and Derrida, we have begun to realize the immense problems posed by an appropriate reading, that is, begun to appreciate the incredibly difficult requirements to which a reading must subject itself if it is to be genuinely critical and reflective.

This course is not the place for a general consideration of hermeneutics or even for a systematic consideration of the specific hermeneutical issues pertaining to Kant’s texts. Nevertheless, let me at least open up those issues with a “hermeneutical preface.”

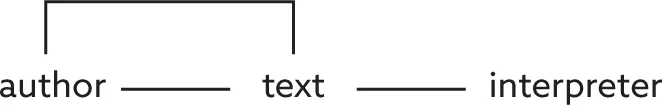

First of all, we need to see that hermeneutics in its contemporary sense bears on our reading of Kant only in view of a certain disengagement of the text from the author’s explicit intentions. The point is that as long as the text is merely the realization of those intentions, the author is the privileged interpreter. In a sense, the author is the only possible interpreter, since any other one would simply set out to duplicate the author’s intentions, reconstructing them from the text. Anything brought to the text by an interpreter other than the author could only distort that text, falsify it. This position amounts to a kind of “hermeneutical positivism.”

On the other hand, suppose a text is not merely the realization of its author’s intentions. Or, rather than put it negatively, suppose there can be layers of sense in the text that exceed the author’s intention. Then the author would not have the kind of privilege just spoken of. Instead, it would be possible for another interpreter to expose layers of sense that remained unthought and unintended by the author. In other words, a productive interpretation would then be possible.

In such a case, one might say that the interpreter can understand the author better than the author understood himself. Now, what is remarkable is that Kant himself openly acknowledges this possibility. In the midst of a discussion of Plato’s use of the word “idea,” Kant writes: “I need only remark that it is by no means unusual, upon comparing the thoughts an author has expressed in regard to his subject, whether in ordinary conversation or in writing, to find that we understand him better than he has understood himself. As he has not sufficiently determined his concept, he has sometimes spoken, or even thought, in opposition to his own intention” (A314/B370).

So at a quite explicit level, Kant’s text grants the very condition which becomes an issue for hermeneutics. In other words, his text opens up a “hermeneutical space”—opens it up and situates itself within such a space.

In addition, there are Kantian texts outlining certain formal hermeneutical principles. I will mention two such principles:

The first is a canon of classical hermeneutics and pertains to the relation between whole and part. Kant expressed it initially in a letter to Christian Garve (August 7, 1783). Here it does not appear explicitly as a hermeneutical principle with the governing relation that of interpreter to text but as a compositional or methodological principle with the governing relation that of writer to text. According to Kant: “Another peculiarity of this sort of science is that one must have a conception of the whole in order to rectify each of the parts, so that one has to leave the matter for a time in a certain condition of rawness, in order to achieve this eventual rectification” (Kant, Philosophical Correspondence 1759–99, tr. A. Zweig, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967, p. 101).

What is prescribed here is that the movement through parts to whole must be supplemented by a regression from whole to parts: the whole must be understood through the parts and vice versa. This demand is a hermeneutical principle, and in the Critique of Practical Reason, Kant accuses some of his critics of failing to observe it. Kant writes that the nature of human knowledge requires that one “begin with an exact and . . . complete delineation of parts.” Yet, “a more philosophical and architectonic procedure . . . is to grasp correctly the idea of the whole, and then to see all those parts, in their reciprocal interrelations, in the light of their derivation from the concept of the whole” (CPr, p. 10).

So in reading a Kantian text, we will want to be attentive to the interplay of whole and part. In order to install such an interplay in our interpretation, I will begin with a provisional glance at the whole and will do so specifically with a series of formulations of the Kantian problem in general. Then, through detailed textual work or, in other words, through the parts, we will try to move back toward that whole, toward regaining it through the parts, toward a “synoptic view.”

The second principle relates the issue of whole and part to the question of definition. Kant writes: “Such a precaution against making judgments by venturing definitions before a complete analysis of concepts has been made (usually only far along in a system) is to be recommended throughout philosophy, but it is often neglected. It will be noticed throughout the critiques of both the theoretical and the practical reason that there are many opportunities to remedy inadequacies and to correct errors in the old dogmatic procedure of philosophy which were detected only when concepts, used according to reason, are given a reference to the totality of concepts” (CPr, pp. 9–10, footnote).

So this principle is a warning against venturing definitions, conclusive determinations of parts, prior to the return from the whole to those parts. In other words, it prescribes a certain initial indeterminacy, one necessary at the outset and only gradually removed in the course of the text. In still other words, it prescribes a certain stratification of the text corresponding to different degrees of determinacy.

This principle is especially important for understanding the typically Kantian way of appropriating traditional concepts: they are taken over with a certain degree of indeterminacy, allowing them to be progressively redetermined at several stages of the text.

So we will want to be attentive to this kind of structure in our reading of Kantian texts. That will require a certain reticence, a certain holding back from the demand for completely determinate concepts.

II. | Introduction to the Course |

BY WAY OF introduction to the Critique of Pure Reason, that is, to the problem with which the text is engaged, I want to:

(1)indicate what the general problem is,

(2)show how, in the development of Kant’s thought, it came to be a problem, and

(3)present a series of formulations elaborating the problem as a whole and moving from a more general level, that of the Prefaces and Introduction of the Critique of Pure Reason, to more fundamental levels.

(1) The general problem.

The general problem of the Critique of Pure Reason is metaphysics. We need to ask how it comes about that metaphysics is a problem for Kant. In what way does it present itself to him as something questionable, problematic? What does he see that is questionable in metaphysics?

Kant exhibits this questionableness by focusing on two features of traditional metaphysics. First, metaphysics is the highest science, in the sense that it deals with the ultimate questions, the most important questions for man, namely, questions concerning God, freedom, and immortality. Kant formulates it this way in the “Doctrine of Method”: “What can I know? What ought I do? What may I hope?” (A805/B833). Metaphysics, since it deals with these ultimate questions, is indispensable. It represents an “inward need” of man, a “natural disposition.” It is not an ornament. Kant maintains that there has always been metaphysics and always will be.

Second, for all its importance, metaphysics has remained a battlefield of endless controversies. It has not been able to enter upon the path of genuine science.

In summary, as Kant writes at the beginning of the Preface in A: “Human reason has this peculiar fate that in one species of its knowledge it is burdened by questions which, as prescribed by the very nature of reason itself, it is not able to ignore but which, as transcending all its powers, it is also not able to answer” (A vii).

This predicament is not, for Kant, a mere accident, a result of error by some people, their failure to work out some problems adequately. It is not a problem that could have impeded mathematics or physics. Rather, its source is a conflict of reason with itself.

The conclusion Kant draws from the plight of metaphysics is the need for a tribunal charged with settling the dispute, assuring lawful claims and distinguishing them from groundless pretensions. This tribunal would resolve the conflict and set metaphysics on the path of genuine science.

The demand for such a tribunal is “a call to reason to undertake anew the most difficult of all its tasks, namely, that of self-knowledge” (A xi). Thus the tribunal takes the form of a self-critique of reason; that is what the Critique of Pure Reason is all about in the first instance. According to Kant: “I mean a critique . . . of the faculty of reason in general, in respect of any knowledge after which it may strive independently of all experience. It will therefore decide as to the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics in general and will determine its sources, its extent, and its limits—all in accord with principles” (A xii).

Thus Kant’s problem is metaphysics, and an interrogation of metaphysics takes the form of an interrogation of reason—specifically, an interrogation of reason with respect to its capacity to gain knowledge independently of experience or, in other words, an interrogation of pure reason. Such a critique is a necessary propaedeutic to metaphysics.

(2) Development of the problem (Inaugural Dissertation).

How did metaphysics come to be a problem for Kant? That is, how did the capacity of reason to gain knowledge independently of experience become questionable?

We can glimpse the answer by looking at the last of Kant’s “pre-critical” works: the Inaugural Dissertation of 1770, presented on the occasion of his inauguration as professor at the University of Königsberg. What is most important is that in the Dissertation, metaphysics is not questionable the way it is in the Critique; thus the transition from the former to the latter is precisely the calling of metaphysics into question.

The general framework of the Dissertation is expressed in the title: “On the form and principles of the sensible and intelligible worlds.” Accordingly, the general framework is provided by the distinction between the intelligible world (things as they are in themselves) and the sensible world (things as they appear to our senses, things as given in experience). Along with this distinction, a connection is posited between the two worlds distinguished: the intelligible world is understood as the substrate or ground of the sensible one.

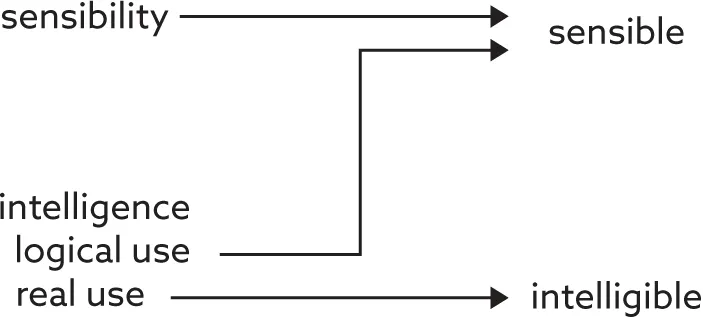

This is a venerable old distinction and way of understanding it, detached by the tradition from Book 5 of Plato’s Republic. In general, it is akin to the Leibnizian distinction between the realm of nature (extended things, phenomena) and the realm of grace (monads, substances). The distinction is duplicated on the side of the subject in the contrast between sensibility and intelligence:

Sensibility is the receptivity of a subject by which it is possible from the subject’s own representative state to be affected in a definite way by the presence of some object. Intelligence (rationality) is the faculty of a subject by which it has the power to represent things which cannot by their own character come before the senses. The object of sensibility is the sensible; that which contains nothing but what is to be known through the intelligence is the intelligible. In the schools of the ancients the first was called a phenomenon and the second a noumenon. (Inaugural Dissertation, §3. Selected Pre-critical Writings, trans. G. B. Kerferd and D. E. Walford, Manchester University Press, 1968)

Sensible things appear to sensibility. This does not entail, however, that intelligence has no relation to sensible things. It can indeed relate to them, but only in its “logical use.” Intelligence can do no more than compare and reflect conceptually on what is given to sensibility.

On the other hand, intelligence also has a “real use.” That is crucial; through the real use of intelligence, we are able to know the intelligible, that is, know things as they are in themselves. According to Kant: “Insofar as intellectual things strictly as such are concerned, where the use of the intellect is real, such concepts, whether of objects or relations, are given by the very nature of the intellect. They have not been abstracted from any use of the senses, nor do they contain any form of sensible knowledge as such” (§6).

The concept of metaphysics is determined in reference to this real use of the intelligence: “The philosophy which contains the first principles of the use of the pure intellect is metaphysics” (§8). Thus metaphysics has to do with knowledge of the intelligible, that is, with our knowing things in themselves independently of experience.

The transition from the Dissertation to the Critique of Pure Reason is precisely Kant’s calling into question the ground and thus the possibility of such knowledge. He questions the objective validity of those pure concepts he had previously taken as providing such knowledge. That is, he raises this problem: how can a concept apply to an object we do not create, an object independent of us, without the concept being derived from a sensible presentation of that object?

Kant’s raising of this problem is documented in his famous letter to Marcus Herz (February 21, 1772). Let me cite an extended passage from that letter:

I noticed I still lacked something essential, something that in my long metaphysical studies I, as well as others, had failed to heed and that, in fact, constitutes the key to the whole secret of hitherto still obscure metaphysics. I asked myself: what is the ground of the relation to an object of that in us which we call the “representation” of it? If a representation is only a way the subject is affected by the...