- 1,612 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tea in Health and Disease Prevention

About this book

While there have been many claims of the benefits of teas through the years, and while there is nearly universal agreement that drinking tea can benefit health, there is still a concern over whether the lab-generated results are representative of real-life benefit, what the risk of toxicity might be, and what the effective-level thresholds are for various purposes. Clearly there are still questions about the efficacy and use of tea for health benefit.

This book presents a comprehensive look at the compounds in black, green, and white teas, their reported benefits (or toxicity risks) and also explores them on a health-condition specific level, providing researchers and academics with a single-volume resource to help in identifying potential treatment uses. No other book on the market considers all the varieties of teas in one volume, or takes the disease-focused approach that will assist in directing further research and studies.

- Interdisciplinary presentation of material assists in identifying potential cross-over benefits and similarities between tea sources and diseases

- Assists in identifying therapeutic benefits for new product development

- Includes coverage and comparison of the most important types of tea – green, black and white

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Section 1

Tea, Tea Drinking and Varieties

Chapter 1. The Tea Plants

Chapter 2. Green Tea

Chapter 3. White Tea

Chapter 4. Black Tea

Chapter 5. Pu-erh Tea

Chapter 6. Tea Flavanols

Chapter 7. Analysis of Antioxidant Compounds in Different Types of Tea

Chapter 8. Cultivar Type and Antioxidant Potency of Tea Product

Chapter 9. Objective Evaluation of the Taste Intensity of Tea by Taste Sensors

Chapter 10. Green Tea (Cv. Benifuuki) Powder and Catechins Availability

Chapter 1

The Tea Plants

Botanical Aspects

Abbreviations

AFLP amplified fragment length polymophism

EC (−)-epicatechin

ECG (−)-epicatechin gallate

EGC (−)-epigallocatechin

EGCG (−)-epigallocatechin gallate

EST expressed sequence tag

F1 first filial generation

GA gallic acid

GABA gamma aminobutyric acid

GC (−)-gallocatechins

GCG (−)-gallocatechin gallate

IPGRI International Plant Genetic Resources Institute

LSI late acting prezygotic gametophytic self incompatibility

PPO polyphenol oxidase

RAPD random amplified polymorphic DNA

RFLP restriction fragment length polymorphism

SSR simple sequence repeat

STS sequence tag site

TF theaflavins

TI Terpene Index

TR thearubigins

Introduction

The cultivated plant species Camellia sinensis ((L.) O. Kuntze) is the source of the raw material from which the popular tea beverage is processed. The species is now cultivated commercially in Asia, Africa and South America. Major producers of the crop include China, India, Kenya, Sri Lanka and Indonesia (Table 1.1). Kenya is currently the largest single exporter of tea (Table 1.2). Although the crop is cultivated in many countries, there are several different types of tea plant, each with its own identifiable character and potential for unique cup quality. Because of this diversity, it is important that the different types of tea plant can be told apart and be classified. Classification, in the biological sense, is the ordering of plants into a hierarchy of classes. The product is an arrangement or system of classification designed to express inter-relationships and to serve as a filing system. The term ‘classification’, however, is often used for both the process of classifying and for the system which it produces.

TABLE 1.1 World Production of Tea (Metric Tons) and Percent Share

TABLE 1.2 World Exports of Tea (Metric Tons) and Percent Share

Classification in Camellia

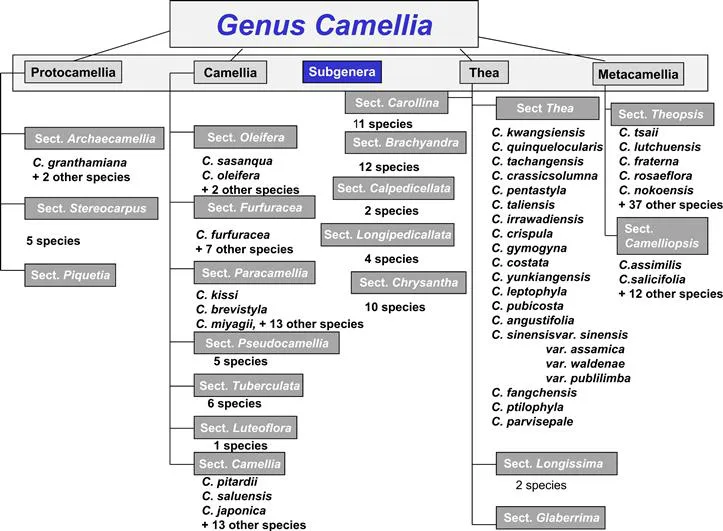

The tea plant (Camellia sinensis) from which the beverage tea is processed, is placed in the genus Camellia. The genus has over 200 species and is largely indigenous to the highlands of Tibet, north eastern India and southern China (Sealy, 1958). Sealy (1958) classified the genus into 12 subgeneric sections, one of which (Thea) contains species of cultivated tea. However, in his monograph Sealy recognized a group of 24 inadequately known species which he called ‘Dubiae’ (Dubious). In their work, Chang and Bartholomew (1984) not only translated the 1981 monograph of the genus Camellia by H.T. Chang but also included publication of new taxa and moved many species treated by Sealy to different sections. They divided the genus into four subgenera (sub groups), i.e. Protocamellia, Camellia, Thea and Metacamellia, and twenty sections (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Summarized Schematic Diagram Showing Species Relationships within Genus Camellia.

Taxonomy of the genus Camellia has been complicated by the free hybridization between species, which has led to the formation of many species hybrids (Chuangxing, 1988). Similarly, most species are unavailable to scientists for study. Genetic relationships and taxonomy has therefore remained controversial and recent interest has seen the discovery of many new species and a revision of taxonomic relationships (Chuangxing, 1988; Lu and Yang, 1987; Tien-Lu, 1992). Tea is, however, the most important of all Camellia spp. both commercially and taxonomically. Though the other non-tea Camellia’s are not widely used to produce the brew that goes into the cup that cheers, several species, e.g. C. taliensis, C. grandibractiata, C. kwangsiensis, C. gymnogyna, C. crassicolumna, C. tachangensis, C. ptilophylia, are used as sources of tea-like beverages in parts of China, which indicates that the economic potential for beverage production from additional underutilized species is very great (Tien-Lu 1992; Chang and Bartholomew, 1984). Seed oil from several species including C. fraterna, C. japonica and even C. sinensis are important sources of cooking oil in China. In addition, many Camellia species are of great ornamental value.

At the species level, tea taxonomy failed to attract much attention and interest once the species of economic importance were identified. It continues to be a low-priority area in most tea research programs. The array of hybrids available which might suggest unrestricted introgression of many species of Camellia and tea compound the taxonomic jigsaw. Several minor taxa have been treated as conspecific with major taxa, although more recently accumulated evidence has shown that these minor taxa have no natural distribution and are derived from hybridization events involving different species (Parks et al., 1967; Uemoto et al., 1980). The taxonomic affinities of most interspecific and intraspecific hybrids are unknown, but could provide clues to the evolutionary organization of the tea gene pool. Information on taxonomic characteristics, genetic diversity and biogeography of Camellia in living collections are scantily documented, though vital in identifying sources of desirable genes (Banerjee, 1992).

Tea was initially classified as Thea sinensis by Linnaeus (Linnaeus, 1753). Following the discovery of its economic importance, and the subsequent extensive collection of indigenous teas from the forests contiguous to the upper Assam–Burma–Tibet borders, two distinct taxa were identified and classified by Masters (1844) as Thea sinensis, (the small-leaved China plant) and Thea assamica (the large-leaved Assam plant). For a long time, Thea and Camellia were considered as separate genera (Fujita et al., 1973) and some authors even considered Camellia to be a ‘section’ under the genus Thea (Roberts et al., 1958; Barua and Wight, 1958).

Another group of authors (Sealy, 1958; Barua, 1965) considered that CameIlia and Thea were so much alike in morphological, anatomical and biochemical features that the classification schemes proposed above were unrealistic. According to them, the apparent difference in leaf pose, patina and pigmentation was a part of the total variation in leaf features. Wight (1962) considered Thea to be synonymous with Camellia and the name Camellia prevailed. Thus, today tea is botanically referred to as Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze, irrespective of species-specific differences. Camellia sinensis is classified under section Thea along with 18 other species (Figure 1.1).

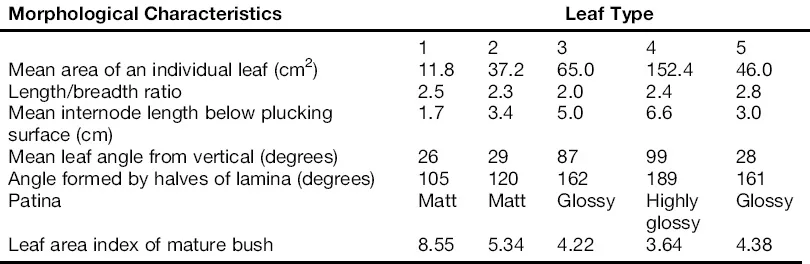

At the species level, several intergrades resulting from unrestricted intercrossing between disparate parents have been documented, but have not been assigned the status of separate species (Sealy, 1958). However, three distinct tea varieties have been identified on the basis of leaf features like size, pose and growth habit. These are the China variety, Camellia sinensis, var. sinensis (L.); the Assam variety, Camellia sinensis var. assamica (Masters) Kitamura; and the southern form also known as the Cambod race, C. assamica ssp. Lasiocalyx (Panchon ex Watt). The three main taxa can be differentiaed by foliar, floral and growth features (Tables 1.3 and 1.4) and by biochemical affinities (Sanderson, 1964; Robert et al., 1958; Hazarika and Mahanta, 1984; Ozawa et al., 1969; Fujita; et al., 1973; Owuor et al., 1987). It is common to find the three different varieties (China, Assam and Cambod) referred to as separate species, namely, Camellia sinensis, C. assamica and C. assamica ssp. Lasiocalyx, respectively (Bezbaruah, 1976). Research has shown that cultivated tea is an out-crosser with an active late-acting pre-zygotic gametophytic self incompatibility (LSI) system (Wachira and Kamunya, 2005a; Muoki et al., 2007). Because of its out-breeding nature and, therefore, high heterogeneity, most cultivated teas exhibit a cline extending from extreme China-like plants to those of Assam origin. Intergrades and putative hybrids between C. assamica and C. sinensis can themselves be arranged in a cline of specificity (Wight, 1962). Indeed because of the extreme hybridizations between the three tea taxa, it is debatable whether archetype (original) C. sinensis, C. assamica or C. assamica ssp. lasiocalyx still exist (Visser, 1969). However, the numerous tea hybrids currently available are still referred to as Assam, Cambod or China depending on their morphological proximity to the main taxa (Banerjee, 1992).

TABLE 1.3 Criteria Used for Differentiating Two Major Tea Varieties and Sub-Varieties of Camellia sinensis

TABLE 1.4 Types of Tea Differentiated on the Basis of Foliar Characteristics

1 = Extreme China

2 = Typical between Assam and China

3 = Typical ...

2 = Typical between Assam and China

3 = Typical ...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Contributors

- Section 1: Tea, Tea Drinking and Varieties

- Section 2: Miscellaneous Teas and Tea Types: Non-Camellia sinensis

- Section 3: Manufacturing and Processing

- Section 4: Compositional and Nutritional Aspects

- Section 5: General Protective Aspects of Tea-Related Compounds

- Section 6: Focused Areas, Specific Tea Components and Effects on Tissue and Organ Systems

- Section 7: Behavior and Brain

- Section 8: Adverse Effects of Tea and Tea-Related Products

- Section 9: Comparison of Tea and Coffee in Health and Disease

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tea in Health and Disease Prevention by Victor R Preedy,Victor R. Preedy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.