![]()

PART ONE

The State of Electoral Institutions and Voter Turnout

![]()

TWO

Electoral Federalism and Participation in the American States

Democracy, at least in the broadest sense, is defined by representation, and a central facet of political representation requires individuals’ participation in government (Hamilton, Madison, and Jay 1961; Lijphart 1997; Pitkin 1967; Piven and Cloward 1988; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). Accordingly, participation rates are frequently used to measure the success of a democracy. It follows that low voting rates elicit concern about the health of a democratic system (Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Verba and Nie 1972). For example, elections are the main form of interaction between policy makers and citizens (Mills 1956; Schattschneider 1960), so low voter turnout weakens the relationship between these two groups—at the heart of political governance in the United States—and can exacerbate bias between those who routinely vote and those who do not (Bartels 2008; Citrin, Schickler, and Sides 2003; Fellowes and Rowe 2004; Griffin and Newman 2008; Hajnal 2010; Hill and Leighley 1992). Low voting rates can also have political consequences (Bachrach 1967; Mill 1962; Schatt-schneider 1960; Verba and Nie 1972). They affect the representativeness and legitimacy of the democratic system and alter the content of the political agenda (Bennett and Resnick 1990; Griffin and Newman 2005; Guinier 1994; Martin 2003; Piven and Cloward 1988; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Teixeira 1992; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995; Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980).1

Ultimately, voter turnout offers one metric for evaluating the health of the democratic system: the engagement of the populace and the link between representatives and represented. This is worrisome for observers of modern American politics. Voting rates in the United States were much lower during the twentieth century than during the nineteenth, and although they have fluctuated over time (more if one examines participation at the state rather than the national level), they have been trending downward since midcentury. Federalism is central to this story. The federal system empowers the American states to determine voting structures within their borders. Since all electoral rules “have explicit or implicit political purposes and assumptions” (Burnham 1987, 109), at any moment in history state electoral institutions reflect the type of democracy rule makers sought to design—limiting the vote in some instances and expanding it in others. Within American federalism, electoral institutions—and by extension state governments—are used to define the subset of the public that is, and is not, going to be represented (though admittedly participation is only one aspect of representation). This process has had lasting consequences for the nature of the American democratic system.

The “Turnout Problem” in the United States

The history of electoral politics in the United States is punctuated by changing patterns of participation. The American electorate’s propensity for political participation was quite different in the twentieth century than in the nineteenth. Unlike the modern era, the mid- to late nineteenth century is generally described as a period of intense political engagement, heightened partisanship, and high voting rates (Avey 1989; Bensel 2004; Burnham 1987; Key 1966; Kleppner 1982; Mayhew 1986). As the country neared the end of the nineteenth century and moved into the early years of the twentieth, the dynamics governing political participation changed radically. An onslaught of Populist and Progressive reforms—legitimizing the electoral process and stripping power from corrupt political machines—fundamentally changed the electoral landscape (Brody 1978; Burnham 1970; Keyssar 2000; McGerr 1986, 2003; Patterson 2002).

One of the Progressive Era’s most pronounced legacies, however, is the dampening of electoral engagement. Turnout rates of the modern American electorate fall well below averages from the previous century (Burnham 1965; Teixeira 1992). Although there has been some ebb and flow in national turnout over time—for example, historians credit the realigning principles of the New Deal for reviving political interest during the 1930s—any vibrancy proved unsustainable. By midcentury the United States witnessed a sizable decline in national voter turnout, and scholars were confronted with a seeming “puzzle of participation” (Brody 1978).

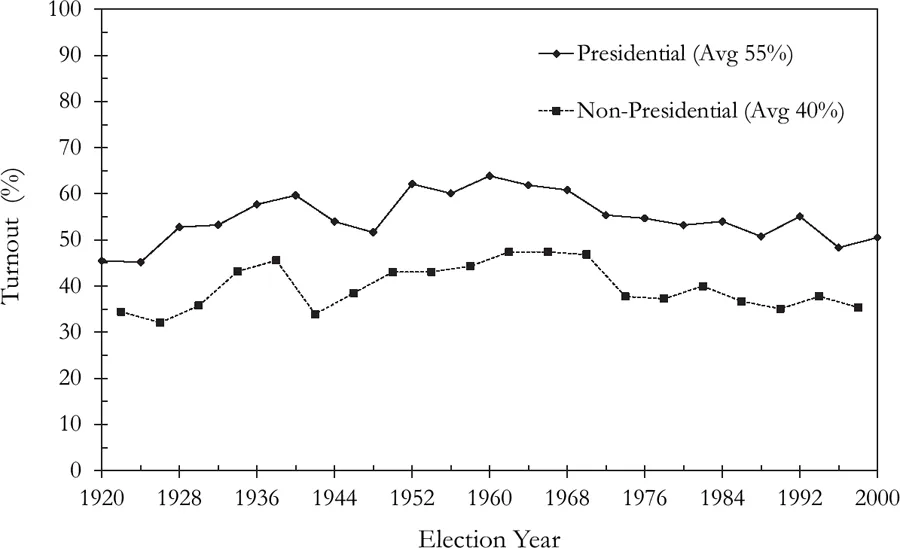

As figure 2.1 shows, national voter turnout in the United States has been low throughout the twentieth century, averaging about 55% during presidential election years and 40% during nonpresidential election years. National voting rates were not particularly high at any time during this period, and turnout in presidential election years, when just over half the population voted, represents the upper bounds of participation. The low and declining turnout during this time is especially puzzling. Throughout the century there were sizable increases in the median education level, white-collar jobs, and real income—demographic variables that have been theorized, at least at the individual level, to affect turnout positively and should have led to an increase (not a decrease) in voting rates (see, e.g., Burnham 1987; Campbell et al. 1960; Leighly 1995; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Rosenstone and Wolfinger 1978; Verba and Nie 1972; Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980). Further, low turnout does not appear to be caused by increased institutional restrictions, because registration and voting have become less cumbersome over time, especially since the 1960s (Brody 1978; Teixeira 1992). So if demographic characteristics and procedural impediments were the sole barriers keeping people out of the voting booth on Election Day, voter turnout should have systematically increased, not decreased, over the past several decades. This is the heart of the so-called turnout problem in American elections.

2.1. National voter turnout trends, 1920–2000

Some of the most influential work on voter turnout and electoral reform in American politics is motivated by a national “turnout problem” approach (e.g., Abramson and Aldrich 1982; Gans 1978; McDonald and Popkin 2001; Piven and Cloward 1988; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Schattschneider 1960; Teixeira 1992; Wattenberg 1998). Although historical comparisons of United States voting rates during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are worrisome, the turnout problem is exacerbated by cross-national comparisons. In the canonical portrayal, voter turnout rates from other developed countries are juxtaposed with American national trends (Burnham 1965, 1982; Lijphart 1997; Powell 1986; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). These cross-national comparisons reveal a startling pattern that characterizes the modern American electorate as essentially nonparticipatory.2

Compared with those of other advanced industrial democracies, voting rates in the United States are strikingly low. For example, Powell (1982) lists five countries that stand out for having low voting rates in general elections: “In India, Jamaica, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States only about two-thirds of the eligible electorate voted in the average national election” (13). Even using presidential turnout rates (the highest rates), comparative analyses reveal that the nation is a participatory laggard. Notably, Powell’s impressive comparison of twenty advanced industrialized democracies reveals that “average turnout in presidential elections in the United States as a percentage of the voting-age population was 54% in the period from 1972–80. In the other twenty industrialized democracies, the average turnout was 80%” (1986, 23–24). According to Powell’s study, America’s national voter participation exceeds that of only one other country—Switzerland. Similar lackluster pictures can be found in Crewe (1981), Dalton (1988), Glass, Squire, and Wolfinger (1984), Jackman (1987), Lijphart (1994), and Verba, Nie, and Kim (1978).

Not only does the United States fall below most of the democratized world in twentieth-century voting rates, the gap is substantial. As Teixeira notes, “Because the highest ranked democracies (Belgium, Austria, and Australia) have turnouts of 90% or more, the gap between the United States and these democracies approaches or exceeds 40 percentage points. Even if one compares the U.S. rate with the average across all twenty democracies (78%), the gap is still 25 points” (1992, 7–8). Further, declining trends in American participation run exactly counter to trends in other countries. While the steady movement in many Western European countries was “toward substantially complete incorporation of the mass public into the political system,” the trend in the United States “since about 1900 [has] been a move toward functional disenfranchisement” (Burnham 1982, 122). These patterns have shaped an unflattering global perception of voting in the United States, leading observers of electoral behavior to conclude that a high level of not voting is not only troubling but also characteristically American.

Yet the “turnout problem” in the United States, which is so often decried and analyzed by comparing today with earlier periods in American history or the United States with other developed countries, actually is an artificial and somewhat institutionally blind way of understanding turnout. It is misleading because it does not take into account that United States national turnout actually means average turnout. Since national turnout rates are typically not recognized as average turnout, the United States is always treated as a deviant—as if somehow the whole country were weirdly non-participatory. This is incorrect in two important ways.

First, the United States is unusual in allowing its subnational units (the American states) to design their own election procedures, especially for national elections. As such, it is not really comparable to other democratic polities once we recognize that, in the cross-national perspective, electoral federalism is unique legally, administratively, and in the number of subnational units involved. This arrangement makes the United States exceptional from that perspective (Ewald 2009; Lipset 1996; Tocqueville 1948). How many other polities, even federal polities, feature fifty variations of rules governing turnout for national elections? None. Yet the turnout problem discussion often fails to recognize this essential fact.

Second, by ignoring the importance of electoral federalism in the United States, both historical and international comparisons of national voting rates mask the impressive variation across the country both in electoral rules and in turnout rates. The states and regions vary tremendously in how they structure registration and voting systems and also in how participatory they are. Subnational turnout rates during the twentieth century have varied not slightly but very considerably. Thus the turnout problem idea, which has been kicking around for decades and has inspired some of the most influential scholarship on modern voting habits (such as Burnham 1965; Powell 1986; Piven and Cloward 1988; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993) and even federal reform initiatives (e.g., the 1993 National Voter Registration Act), misframes twentieth-century voter turnout in the United States.

This study moves beyond the classic turnout problem approach. I argue that voting in the United States is exceptional, but not because twentieth-century voting rates were low or because the electorate is oddly deviant in its tendency not to vote. Instead, it is the electoral environment that is exceptional. I showcase American federalism as critical to shaping US voter turnout, and I view electoral federalism as constitutive of the nation’s voter turnout—as fundamental to political participation. To understand modern voting behavior, we need to explore the federal arrangement in the states and its effects on subnational voting rates. Participation, as Powell and many others have pointed out, is “facilitated or hindered by the institutional context within which individuals act” (1986, 17); thus the large degree of institutional variation—a by-product of American federalism that leads to variation in state and regional turnout—needs to be evaluated. Further, institutional development casts a very long shadow across the states and regions. Historical analysis is essential for recognizing the slow evolution of state electoral systems and the jurisdictional variation in twentieth-century voter turnout. By examining this relationship subnationally and historically, this book celebrates the developmental and temporal dimensions of American federalism.

Voter Turnout: A Product of American Federalism?

The most impressive responsibility vested in the American states by the federal system is their governance over electoral processes. Since the country’s founding, the individual states have created and implemented electoral laws within their borders with minimal federal intervention, essentially creating fifty unique sets of rules. Still today, nearly all electoral institutions originate at the state level. Even the power to determine who is considered qualified to vote—to literally define the electorate—has been delegated to the fifty states. And the way the states have made these determinations, and the basis for them, has varied greatly over time. This individualism was originally justified by the belief that state and local authorities knew their particular circumstances better than outsiders did and could therefore fashion laws that suited their specific needs (even if they did so in normatively objectionable ways). This decentralized electoral system has important ramifications. Variation in state rules about how, or whether, individuals can participate in government affects the political system. By implementing expansive and restrictive electoral institutions throughout the twentieth century, the states have established the limits of participation and shaped American democracy.

Alongside this system of relative state autonomy lay the powerful interests of the federal government. Throughout the twentieth century a tension existed between state and federal perspectives on norms of exclusion and participation within the electoral system. Incongruences have arisen in how easily certain classes of citizens could qualify, register, and ultimately participate in the electoral process. Consequently there were important moments when the federal government was compelled to intervene and supplant state electoral authority in order to establish more uniform and just voting practices. Apart from these important instances of federal action, however, the states have designed and maintained the types of electoral environments they most prefer, anticipating how various electoral rules might affect participation. The evolution of institutional expansion and restriction by the states, coupled with federal involvement, has defined electoral politics in the United States. At its core is the connection between institutional design and anticipated political response. This has had important consequences for the quality of American democracy throughout the twentieth century and before.

I appreciate the importance of the American federal system in this capacity and treat the states as units of analysis. This is a departure from the individual-level framework often used to study American voting behavior (see Leighley 1995 and Lewis-Beck et al. 2008 for a review of this extensive literature).3 Although our understanding of American voting behavior has benefited greatly from the individual-level behavioral framework, research focusing exclusively on the attributes, characteristics, and demographics of individual voters and nonvoters typically neglects the interactive effects and structural patterns surrounding elections. Political behavior does not occur in a vacuum. We need to evaluate the setting within which political actors are forced to behave (Ewald 200...