- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

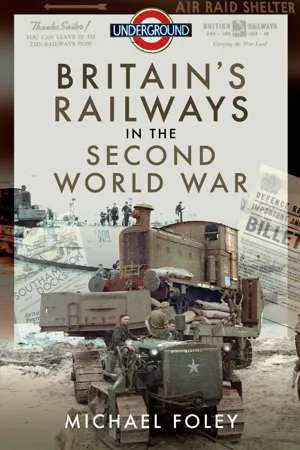

Britain's Railways in the Second World War

About this book

A fascinating account of the British Railways system's vital role in the defense of the country and support of the Allied forces during WWII.

The outbreak of the Second World War had an enormous effect on the railway system in Britain. The 'Big Four' companies put aside differences and worked together for the war effort. The logistics of transporting troops during the evacuation of Dunkirk and the preparations for D-Day were unprecedented. Meanwhile, they had to cope with the new and constant threat of aerial bombing. As a result, the railway system effectively served as another branch of the military.

At the end of the war, Winston Churchill likened London to a large animal, declaring that what kept the animal alive was its transport system. The metaphor could have been applied to the whole of Britain, and its most vital transport system was the railway. This book brings to light the often-forgotten stories of the brave men and women who went to work on the railways and put their lives on the line.

The outbreak of the Second World War had an enormous effect on the railway system in Britain. The 'Big Four' companies put aside differences and worked together for the war effort. The logistics of transporting troops during the evacuation of Dunkirk and the preparations for D-Day were unprecedented. Meanwhile, they had to cope with the new and constant threat of aerial bombing. As a result, the railway system effectively served as another branch of the military.

At the end of the war, Winston Churchill likened London to a large animal, declaring that what kept the animal alive was its transport system. The metaphor could have been applied to the whole of Britain, and its most vital transport system was the railway. This book brings to light the often-forgotten stories of the brave men and women who went to work on the railways and put their lives on the line.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Military Railways

It is a surprising fact that the British military, who were normally so averse to accepting new ideas or technology even as late as the First World War, were eager to use the railway system from the mid-nineteenth century. The public at home had been horrified to learn of the condition of British troops in Crimea, which was widely reported in The Times and was mainly due to the difficulty of moving supplies to the front because of the terrible road conditions in the area.

It was a man named Samuel Morton Peto who exerted a great influence on the military in accepting the new technology and so changed conditions for the better for the British troops. Peto had been involved in the building of the Great Western Railway, and under the direction of the Secretary of State for War, the Duke of Newcastle, was responsible for building a railway from Balaclava to Sebastopol. The 7-mile line was completed in just over seven weeks and was of a standard gauge of 4 feet 8½ inches. It was due to the capability of the line in bringing up supplies that the siege of Sebastopol was successful. The line was also the first to be used by a hospital train.

The Crimean War was a turning point in military history as it was realised that the army needed more than just fighting men. It also needed a properly organised level of services, which led to the formation of the Land Transport Corps, the forerunner of the Royal Corps of Transport. However, this wasn’t easy to achieve. The Land Transport Corps were disbanded as soon as the war ended. There was then some dispute over the fact that the officers of the corps were seen as part of a civilian rather than a military organisation.

According to an article in the Hampshire Chronicle in 1856, a new corps, the Military Train, was being created, which would become a permanent department of the army. Its duties would be to convey all stores, ammunition and equipment. It was to be formed from the most eligible volunteers of the disbanded Land Transport Corps.

In a later development, the Engineer and Railway Staff Corps, affiliated to the Royal Engineers, was founded in 1865. The aim of this corps was to ensure that all the railway companies took combined action when the country faced danger. Before a war began, they were to prepare schemes for transporting troops to areas where they were needed. This meant that for most of the time they were in existence, they had hardly anything to do. The corps were also unique in consisting entirely of officers.

The success of the Crimean railway line obviously had an influence on military tactics. In 1896, Sirdar Horatio Kitchener was responsible for the construction of the Sudan Military Railroad during the Mahdist War, which was built to supply the Anglo-Egyptian army. Although the line was part of a planned railway, it was created purely for military purposes rather than for bringing civilisation to the area, although it later became part of the Sudan Railway.

Lord Cromer had agreed the building of the railway but expected it to be a cheaper, narrow gauge construction of 2 feet or 2 feet 6 inches. Instead, Kitchener, who had previously met Cecil Rhodes, built a line that was of a 3-foot 6-inch gauge. Rhodes had already begun to build a railway of similar gauge between Kimberley and Bulawayo.

Previous to this, the first Royal Engineers Railway Company had been formed in 1882. They were involved in the Mahdist War in Egypt, and also later in the Sudan. When they returned from the Sudan, the new company was based at the Chattenden and Upnor Railway, close to the Royal Engineers’ headquarters at Chatham.

As well as the British Army’s growing awareness of the vital role of the railways during times of conflict, there were other examples of military use in the nineteenth century. The railway proved effective in the American Civil War, particularly in the use of armoured trains.

The new British Army Corps of Royal Engineers was active during the Second Boer War (1899–1902). Armoured trains were a new feature of the conflict for the British, although were not to prove as effective as was hoped. This was shown on 15 November 1899, when Winston Churchill, acting as a correspondent for the Morning Post, joined a scouting expedition on an armoured train. The train was captured by the Boers and Churchill became a prisoner of war for a brief period before managing to escape in mid-December.

After the Boer War, the Royal Engineers Railway Company returned to Chattenden before moving to Longmoor, Hampshire, in 1905.

The early success of the first military railways led to the development of narrow gauge railways during the First World War. There were a number of these built to supply the forces on the Western Front, often carrying supplies across land unusable by any other form of transport.

The greatest success of the railways in the First World War was evident when the Americans arrived. The British and the French asked the Americans to organise nine Railway Engineer units in 1917. There were 1,065 men in each unit; some were construction teams, others were workshop units. After a call for men working in other army units who had railway experience, many of the railwaymen went to Europe.

The Americans operated US trains on the French railway system. They then set up narrow gauge railways leading from railheads to the front line. The trench railways were 60-centimetre gauge (23⅝ inches). There were 7 to 10 miles of railway for each mile of the front. The engines were mainly steam but there were also diesel engines near the front to avoid the enemy spotting the steam from the other engines.

2. The use of railways by the army increased greatly in the First World War. On the Western Front, narrow gauge railways were the only efficient way to supply the men on the front line.

It wasn’t only on the front line that military railways were of use. As the military camps back in Britain began to grow in size, they often had their own branch lines built to carry new recruits to their training centres. As the need for more men became acute, the size of training camps grew until those such as the enormous establishment at Clipstone, near Mansfield in Nottinghamshire, became common. Clipstone expanded to hold thousands of men, although most of the early arrivals left the train at Edwinstone station and marched to the camp. This was despite the fact that sidings had been built to the camp on which goods trains were used to deliver supplies. It appears that trains were considered better employed to carry military supplies than to carry the men.

Many of the early military camps of the First World War era were built in remote places. This was the case with RAF Cranwell, Lincolnshire, when it opened as a Royal Naval Air Service base in 1915. It soon became apparent that road transportation of bulk supplies to the camp from Sleaford wasn’t practical. A railway line was needed but there was some dispute over who should build it: the Board of Trade or the Admiralty? It was eventually paid for by the Admiralty.

The army were building their own railways and by 1914 there were two regular and three reserve Royal Engineers Railway Companies. These men were sent to France to build the railways to the front, along with Labour Companies to act as navvies.

3. An army camp close to a railway line, location unknown.

The Railway Executive Committee was responsible for recruiting substantial numbers of employees from the larger railway companies in Britain for these units. Around half the officers for the reserve units were from the rail companies. The rest were from overseas railway companies. Some of the men serving in the same companies were recruited together and formed pals units, although this tailed off as the size of the RE Railway Company grew.

At the end of the First World War, many of the locomotives used in France were returned to Britain and put into storage, where they were forgotten and left to deteriorate. Many of these had been built by companies such as Hunslet, Kerr Stuart and Alco for specific use on the narrow gauge railways on the Western Front. Being left to rot was a waste of engines that in most cases were only a few years old and could have been used elsewhere.

The headquarters of the railway companies was still at Longmoor, where the reserve companies trained every year between the wars using the Woolmer Military Railway.

There were some historic military train connections at Shoeburyness Artillery Barracks in Essex up to the late twentieth century. The camp had its own railway system and they were given the Kitchener Coach, which had been built by the Metropolitan Carriage and Wagon Company in Birmingham in 1885 for Kitchener’s Suakin-Berber military railway that was constructed in the Sudan. The railway was never finished and closed soon after it was begun. There was a parliamentary scandal about the railway, so the War Department decided to bring back all the railway vehicles, including Kitchener’s Coach. There is some doubt as to whether Kitchener used it much but it has retained his name. At Shoeburyness, this coach was used to entertain dignitaries visiting the site. When Shoeburyness closed, the coach went to the Museum of Army Transport at Beverley, in Yorkshire. When this museum closed, the coach was moved to the Royal Engineers Museum at Gillingham, in Kent, and then to Chatham Historic Dockyard, where it remains on display.

By the time the Second World War began, it was not only the civilian railways that were to play a part in the conflict. Alongside this was a better organised military railway group, which worked with the main railway companies while using their skills to provide transport for the Allied forces in many parts of the world.

Chapter 2

Railways Before the Second World War

The early railway system was a collection of hundreds of small companies that sprang up from the 1830s onwards, with the smaller ones being successively swallowed up by those that prospered more quickly. From the conception of the railways as a form of transport, each company was legislated by its own Act of Parliament. By the mid-nineteenth century, Parliament had agreed the building of nearly 300 railways, although not all of them were completed.

The cost of constructing a railway depended on the part of the country in which it was situated. The more difficult terrains incurred extra expense, which often led to the collapse of the company. Consequently, by the time of the outbreak of the First World War, there were about 120 railway companies in Britain.

The railway system continued to expand, with the larger companies acquiring the smaller ones, although a number of small railway companies maintained their independence, even when the government took control during the war. After the war ended, the railways came close to being nationalised, a threat that was to hang over them for years.

When Eric Campbell Geddes put forward his Cabinet paper in 1921, he suggested that the railways in Britain be formed into five or six groups. The Railways Act 1921 came into force on 1 January 1923 and the newly amalgamated companies became known as the ‘Big Four’ – a name coined by the Railway Magazine in February 1923. These were the Great Western Railway (GWR), the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS) and the Southern Railway (SR) companies. There was also a separate London Passenger Transport Board.

Competition between the Big Four was evident. There had been a time when no railway company would dare to allow a train to trespass on to another company’s lines. In America there was an incident of this happening, resulting in the tracks of the connecting line being pulled up to stop the offending train returning to its own lines. There is a rumour that this once happened in Britain, although there is no direct evidence of it. By the outbreak of the Second World War, there was a great deal of co-operation, with tolerance of trains using other companies’ tracks.

4. Railway service badges were of twofold use during the war. They showed that a man was working on the railway and not shirking his duty by avoiding service in the forces, and they were also a way of recognising employees at security conscious railway depots. Here are examples of employees’ badges for each of the Big Four: the Great Western Railway; the London, Midland and Scottish Railway; the London North Eastern Railway; and the Southern Railway.

The London, Midland and Scottish Railway was claimed to be the largest transport organisation in Europe. Before the war, the company operated more than 7,000 miles of track across the UK. It was the only British railway company to serve England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. They also had a chain of twenty-eight hotels, twenty-five docks, harbours and piers, a number of large engineering workshops, and sixty-six steamships, as well as owning thousands of houses. They were more concerned with carrying freight than passengers. The two main con...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Also by Michael Foley

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Military Railways

- Chapter 2 Railways Before the Second World War

- Chapter 3 1939

- Chapter 4 1940

- Chapter 5 1941

- Chapter 6 1942

- Chapter 7 1943

- Chapter 8 1944

- Chapter 9 1945

- Chapter 10 Reflection

- Afterword

- Appendix I Second World War Railway Memorials

- Appendix II Commemorative Second World War Locomotives and Railway vehicles

- Glossary

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Britain's Railways in the Second World War by Michael Foley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.