![]()

1: A GLIMMER OF OPPORTUNITY

The Setting

And they came to Ophir, and fetched from thence gold, four hundred and twenty talents.

—1 Kings 9:28

… rich and extensive deposits, the real importance of which has not yet been fully appreciated.

—Territorial Enterprise, Genoa, Utah Territory, May 21, 1859

In the early 1850s a small colony of would-be miners began to scour the hills of what is now called the Virginia Range, running parallel to the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada. Flakes of California gold occurred in gravels and sands known as placers along a broad north-south swath on the western side of the Sierra. Conventional wisdom maintained that these deposits resulted from the disintegrating fringe of the mother lode, the hypothesized golden core of the mountain range. It seemed reasonable that the other side of the Sierra might also bear the eroded residue of this miraculous, mythical deposit.

As early as 1850, Mormon settlers along the eastern Sierra were reputed to have discovered placer gold, dust left in alluvial sands, but the church hierarchy of the Latter-day Saints discouraged mining.1 Gold rushes had the potential to inspire uncontrollable human tidal waves that might dilute Mormon society. The Saints had, after all, come to the Great Basin to establish the State of Deseret, a Utopia populated only by the faithful.

No church prohibitions could effectively discourage outsiders, however. Using the same technique to wash placer deposits that was employed in the California gold country, prospectors in 1851 slowly worked their way up from the Carson River. They soon found what Mormons had apparently discovered a year or two before: the sands, deposited over the millennia by occasional flooding from Sun Mountain above, contained specks of gold, or “color,” as they called it.

These early prospectors were part of the backwash from the California Forty-Niner days. That rush had drawn more people than could profit for long there. Like a large colony of bees in search of pollen, the California mining community sent scouts all along the Sierra. Each time word returned of mineral wealth, the resulting feverish excitement rivaled any dance honeybees could muster, and off swarmed the miners to investigate the possibilities of new riches. The prospectors who searched the eastern Sierra were part of this movement, but throughout most of the 1850s they located only meager deposits.

A severe terrain greeted the adventurers who crossed the Sierra into the Great Basin. When visiting Virginia City, it is still possible to perceive what the early explorers encountered, although years of stripping the land have destroyed the fragile ecosystem, leaving the high, cold desert even harsher than before. During the summer, the ravines and gullies leading up to Sun Mountain (now Mount Davidson) and the site of Virginia City are hot and dusty. The air is filled with the sounds of insects clacking about. Nearly everything is brown or gray, whether soil, rock, plant, or animal. Only a desert flower or the gray-green juniper and piñon pines change the monotony. Occasionally, one encounters an overpowering and pungent floral fragrance. At this, even those who are most immune to allergies feel their lungs tighten, and breathing grows difficult.

In winter, the same place can be a scene of sudden change. Snowmelt turns sparse soil into quagmires. A fierce wind can bring a storm in a matter of minutes and send it away just as quickly. It is not uncommon for the blizzard of the morning to yield to the sun and melt away in the afternoon. Without clouds, even the winter sun can bake everything dry in a few days, but a clear sky also signals bitter cold at night. The commonly heard saying, “Nevada has two seasons, winter and summer, and they alternate daily,”2 is hardly an exaggeration.

At the foot of ranges and ravines, where water could collect, settlers found rare oases, which raised their hopes for agriculture. It was the higher elevations, however, where neither soil nor flora hid the bones of the land, that beckoned the early prospectors. During the 1850s, these explorers searched the eastern slope of the Sierra and the ranges immediately to the east. A few promising deposits of gold-bearing sands provided some encouragement and income, but throughout most of the decade, there was no reason to favor one ravine over another. Still, the discoveries gave hope to those who believed in an eastern counterpart to the California gold country. In 1859 the Territorial Enterprise observed:

A great number of very rich quartz specimens have been found in Gold Canyon and vicinity [present-day Virginia Range], gold is known to exist in considerable quantities throughout the entire range of hills on the east of the chain of valleys skirting the Sierras from Walker's River [south of the Virginia Range] to Pyramid Lake [north of the Virginia Range], and it is reasonable to conclude that there must exist also in those hills a vast amount of gold-bearing quartz which will at no very remote period be a source of great profit to the capitalist and the miner, and be one of the chief sources of wealth to our country.3

The California experience had shaped expectations in the Great Basin. Prospectors looked for placer gold and assumed that deposits were widespread, as they were in the multitude of California valleys and streambeds.4 And as they had on the other side of the Sierra, these miners used simple methods to extract the gold, relying on the weight of the mineral to cause it to sink faster than worthless sand. Most often, they used rockers or long toms, wooden troughs with small ridges at the bottom, in which they shook and washed sand until the gold settled out and the worthless dirt flowed away. When water was scarce, miners used mercury, which attracted the gold, but that method was more costly. Groups of men thus worked just as they had in California, up and down the ravines, wherever likely-looking sands had gathered. Wealth would be cumulative, not concentrated, and strikes would emphasize the promise of the entire region, not of specific locations.

A few people realized that there were possibilities other than gold in this land. Much has been made of Hosea Ballou Grosh and Ethan Allan Grosh, brothers who identified a ledge of local silver as early as 1856. A succession of tragedies prevented them from revealing or developing their discovery. On August 19, 1857, Hosea struck his foot with a pick, and two weeks later he died of blood poisoning. In November of that year, Ethan Allan stumbled onto a mountain blizzard while crossing the Sierra and died of exposure.5

The brothers figure prominently in local folklore because their plight underscores the chancy, dangerous nature of early prospecting—and, of course, it makes a good story. The anecdote also suggests that some were not limited by the idea of the golden mother lode and instead sought other mineral possibilities in the austere mountains of the Great Basin. Nonetheless, for most in the 1850s, the canyons of the eastern slope of the Sierra provided an opportunity to eke out a modest living from placer gold, while continuing a search for more promising sands.

Records of the early community in Gold Canyon and the vicinity of Sun Mountain, although rare—and suspect—do offer some information. Those working in the area established a mining camp in Gold Canyon by the early 1850s, but they almost all abandoned it during the height of summer for lack of water, which was needed to work the claims. The mining itself was “monotonous and colorless,” according to nineteenth-century historian Eliot Lord, who interviewed many of the participants. Miners' crude dwellings made of stones, sticks, and brush dotted the landscape near promising diggings. In winter, the miners retreated to abodes only slightly better, constructed of stone, mud plaster, canvas, and boards. Window glass was an unobtainable luxury. Chimneys were rare. Holes in the roof were the standard means of getting rid of smoke.6

Entrepreneurs built a crude station house at the foot of Gold Canyon during the winter of 1853–54, and soon afterward they added a combination store, saloon, and bowling alley farther up the ravine. These facilities supplied local miners with provisions, liquor, clothes, and entertainment. Fresh meat relieved the drudgery, and miners always welcomed a successful hunt or local ranchers who would occasionally “drive a cow or calf up the cañon, slaughter the animal at some convenient point and sell portions as required, or roast the whole by a barbeque.” Journalist-author William Wright maintained in 1876 that “the people … though not numerous, were jovial. They were fond of amusements of all kinds. Nearly every Saturday night a ‘grand ball’ was given at ‘Dutch Nick's’ saloon.”7

Many Mexicans numbered among the early miners. Only a few years before, the entire region had been part of Mexico. Treaties may have placed land under the control of the United States government, but Spanish-speaking people continued to live there. Like Euro-American prospectors, Mexicans found reason to cross the Sierra into the Great Basin. In addition, Chinese laborers and miners worked in the area of Gold Canyon. Together with American Indians—the Northern Paiutes, whose existence continued largely unchanged—these groups formed a complex, international society early in the history of the mining district.8

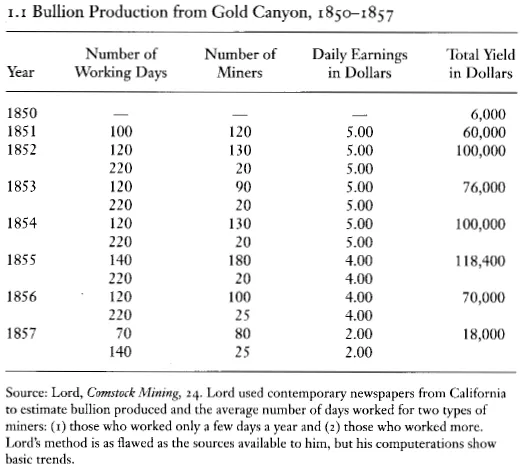

A crisis occurred in the community in 1857. Both earnings and the number of miners had declined since 1855. Nearly two hundred men had depleted the richest sands, and no one had made comparable new discoveries. Gold grew more elusive, and to make matters worse, miners now faced drought, endemic throughout the West. Without water, it was nearly impossible to work the gold-bearing sands. Earnings dropped dramatically (table 1.1); 1857 was a bad year, and 1858 showed no improvement. Many left for more promising possibilities.

It was clear that the placer diggings would fail without development of a more reliable supply of water. The remaining miners organized, created rules for what they called the Columbia Quartz District, and hoped that investors would find the prospects attractive enough to fund ditches to supply the region with water from the nearby Carson River. At the same time, the Territorial Enterprise began promoting the mineral possibilities of the region, calling for capitalists to develop the single ingredient—water—that distinguished the eastern slope from the California goldfields.9 Again, the miners relied on the familiar; some drastic change would need to occur if the mining colony was to survive.

This was the situation in which miners and prospectors of the western Great Basin found themselves early in 1859. The Great Basin is prone to false springs, times when temperatures rise, plants blossom, and mountain snows begin to melt. Typically, blizzards and freezing weather follow, killing young buds and dashing hopes that summer has nearly arrived. A false spring settled upon the Comstock in January 1859, and the wintering, dormant miners used the opportunity to return to work. There must have been little hope of finding new, profitable placer sands at the base of local ravines, because most of the exploration appears to have been higher on the mountain. Groups heading toward Sun Mountain from Gold Canyon to the south and from Six Mile Canyon to the east focused new attention on rocky slopes, where alluvial deposits were unlikely.

It would have been natural for the prospectors to search such heights apprehensively. At the base of canyons, they had only needed to shovel gold-bearing placer sands into rockers to earn a living. Nature had already accomplished most of the milling and processing. As miners searched for the source of the gold higher on the mountainside, they feared that it would be locked in stone when they found it. To work a solid ore body, a miner had to remove large amounts of rock, crush it, and transport it to a stream at the base of the canyon—all of this necessary before the material could be treated like placer sands. It was hard work, and it was costly.

The year before, for example, the Pioneer Quartz Company had resorted to working a ledge near Devil's Gate down Gold Canyon, where workers crushed and processed about five tons of rock. It yielded only three and a half ounces of gold, worth about $42. The company evaluated the result and decided it did not justify further work.10 With such experience in mind, the miners likely ascended Sun Mountain without enthusiasm. Still, they had little choice, aside from leaving the district. With the profitable alluvium exhausted, the remaining option was to search for the source of the placer sands in the hope that whatever ore resulted would be sufficiently rich to justify the arduous task of milling.

In all likelihood, astute prospecting and intuition had little to do with identifying the quartz gold-bearing ledge on the mountainside. Besides the Grosh brothers, James “Old Virginny” Finney, longtime local miner, stumbled into and claimed the ore as early as 1858. Local tradition failed to note others who certainly had also recognized the mineral-bearing strata. Logic had long before told the miners that higher deposits must exist, since there had to be a source for the placer gold-bearing sands at the base of the canyon.11

Unexpected success awaited those who explored the heights of Sun Mountain. Indeed, it would be months, arguably even years, before people fully understood the degree of success. During January 1859, Finney, John Bishop, Alexander Henderson, and John Yount returned to the steep slope of Sun Mountain. They began working with the soil of a mound at the head of Gold Canyon and easily obtained a yield that quickly proved promising. Although clearly not alluvial sand, the outcropping was sufficiently decomposed to make pulverizing of rock unnecessary. The material caught in the bottom of each rocker glittered. The men named the site Gold Hill and immediately established a camp. Prospects in the district suddenly looked better than they had since 1857, if not before. The site promised about $12 a day for each miner.12 The only question was how long it would last.

Word spread through the district, and local miners came to declare their interests in the area. Consistent with custom in the California gold country, the original prospectors claimed only that portion of the site that they could reasonably expect to work. Promising deposits nearby remained there for the taking, the miners working on the assumption that the wealth was diffuse, not concentrated, and that it was impossible for a few men to monopolize an entire district.

Alva Gould soon joined the original four. Within days, Henry Comstock, James Rogers, Joseph Plato, Lemuel “Sandy” Bowers, and William Knight posted their own claim nearby. They immediately began to sink a shaft to determine the depth of the resource. Eight feet of consistent yield justified the investment of labor to build a crude flume to carry water from a stream on the south side of Sun Mountain.13

By the time spring arrived, work was under way on the new prospects, and entrepreneurs were developing more secure sources of water. The return for a day's labor ascended to unprecedented values. The Territorial Enterprise reported in April 1859: “The diggings are in depth from 3 to 20 feet, and prospects from 5 to 25 cents to the pan, from the surface to the bedrock. Bishop & Co., two men, made during the week from $25 to $30 per day; Rogers & Co., two men, from $20 to $40 per day, and F. D. Casteel $10 per day, working alone and packing the dirt about 60 yards.” The newspaper added that with sufficient water, “from $50 to $100 per day per man could be made with ease.” A week later, the newspaper estimated that claims were worth “from $4,000 to $5,000 per share.” Even if such a statement were outlandish exaggeration, clearly the prospects had improved dramatically. Gold fever gripped the community. The miners worked from dawn to dusk, obsessed with the quest for wealth. The normally freewheeling society turned serious. As the Territorial Enterprise observed in April 1859, “The miners are generally temperate and industrious, and whiskey has, therefore, become a drug in the market, with a downward tendency.” They had been bitten by the gold bug, and a reversal of fortune was nowhere in sight.14

Miners began sinking more shafts in May 1859 to test the depth of deposits. Again they found the resource deep and consistent in value. The Enterprise reported that a small claim, 5 by 40 feet, had sold for the unprecedented sum of $250. It was the equivalent of about a month's earnings at the new inflated rate.15 Gold Hill would remain a hotbed of activity for some time.

During the late 1850s, a nearby colony of miners also worked and prospected Six Mile Canyon, extending to the east from Sun Mountain. Encouraged by the success of Gold Hill and driven by a similar lack of viable alluvial sands, some from this group began to search uphill during the spring of 1859, just as their Gold Canyon counterparts had. Finally, on June 8, Patrick McLaughlin and Peter O'Riley,...