This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The meaning of life is a common concern, but what is the meaning of midlife? With the help of illustrious writers such as Dante, Montaigne, Beauvoir, Goethe, and Beckett, The Midlife Mind sets out to answer this question. Erudite but engaging, it takes a personal approach to that most impersonal of processes, aging. From the ancients to the moderns, from poets to playwrights, writers have long meditated on how we can remain creative as we move through our middle years. There are no better guides, then, to how we have regarded middle age in the past, how we understand it in the present, and how we might make it as rewarding as possible in the future.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Midlife Mind by Ben Hutchinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Self Improvement. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Personal DevelopmentSubtopic

Self Improvement1

Crisis and Grief:

The Invention of Midlife

Crisis: Do or Die

Like sex, the midlife crisis was invented in the 1960s. If intercourse began, according to Philip Larkin, in 1963, the midlife crisis arrived shortly afterwards, in 1965. First published as an academic article in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis, Elliott Jaques’s essay ‘Death and the Midlife Crisis’ launched the term in scientific – and rapidly also popular – discourse.1 Although the term ‘midlife’ had first appeared in 1895 (defined in the dictionary as ‘the part of life between youth and old age’), it was only in the 1960s that it became automatically associated with the idea of having a crisis. That the two terms have become so indissoluble testifies to the concept’s resonance; equal parts self-justifying myth and self-fulfilling prophecy – you fear you are going to have a breakdown, so you do – the midlife crisis has become a staple of films and novels. No narrative of achievement, no biography of becoming is complete without the moment of self-doubt in the middle act, the crisis of confidence that must ultimately – such is our cultural obsession with success – be triumphantly overcome. In part this corresponds to our lived experience as we settle into the long, slow process of getting older, but it also reflects the nagging sense of hollowness behind the modern Western story of security and prosperity. The idea of the ‘midlife crisis’ crystallizes not just our dawning sense of personal mortality, but the way we come to question the very meaning of our lives as we reach middle age. Is that all there is?

How we answer this question depends, according to Jaques, on whether we conceive ourselves as creative. The biological facts of the crisis, as he sees them, are rapidly established: it occurs around the age of 35, it can endure for several years, and it varies in intensity according to individual circumstances and temperament. It is also, in Jaques’s telling, decidedly male; ‘Death and the Midlife Crisis’ is most definitely not ‘Death and the Maiden’, neither in the examples adduced nor in the understanding of the crisis as essentially ‘creative’ in nature. Although the post-industrial era sees the midlife mind becoming increasingly female, its conceptualization as ‘crisis’ remains resolutely male well into the post-war world. The male menopause (the ‘mano-pause’) seems to invite psychoanalysis, no doubt because it is metaphorical rather than physiological, but perhaps also because it is (supposedly) only temporary, a passing lull presaging renewed productivity. Men merely pause where women menopause.

Reading Jaques’s essay more than half a century after it was first published, it is striking not only in how old-fashioned his attitudes now seem – his exclusive focus on men, his assumption that family life ‘ought to’ have become established by the time one reaches one’s mid-thirties – but in how problematic any attempt to universalize the midlife crisis must surely be. Whether or not it actually exists as anything more than a popular myth (a point much disputed by specialists), it takes different forms in different people: one man’s meltdown is another woman’s maturity. Yet Jaques reduces these many narrative threads to a single story: the midlife crisis as discernible in the work of ‘great men’. While his impressionistic approach to the crisis seems problematic from a scientific point of view – he ‘gets the impression’ that the death rate between the ages of 35 and 39 jumps markedly in creative artists, and his invocation of predetermined ‘genius’ is little more than rehashed romanticism, underpinning as it does his reading of artistic biographies (‘the closer one gets to genius . . . the more striking and clear-cut is this spiking of the death rate in midlife’) – the popular success of his diagnosis suggests that he has a point. Creativity changes – pauses, pivots and metamorphoses – as we reach middle age.

What new forms does it take? Jaques terms the post-crisis period that of ‘sculpted creativity’. By this he means to indicate a newfound attentiveness to ‘externalized material’ as well as to internal, immaterial thoughts, an interest in execution as well as inspiration. While there is an element of circularity about this argument – Jaques derives his models of Romantic, intuitive youth and Classical, reflective middle age from the canon of male artists (Beethoven, Shakespeare, Goethe and so on), and then applies this model back on to them – it is clear what he means. Desire and impatience give way to serenity and acceptance.

Attaining this enlightened state, however, requires passing through what Jaques terms the ‘purgatory’ of the midlife crisis. What has to be purged are any remaining illusions about one’s own immortality – fantasies of which, according to Sigmund Freud, we all secretly maintain. As we stop growing up and begin growing old, we are forced to face up to the brute reality of our eventual death; we can no longer continue pretending that only other people die. The future tense becomes the future past.

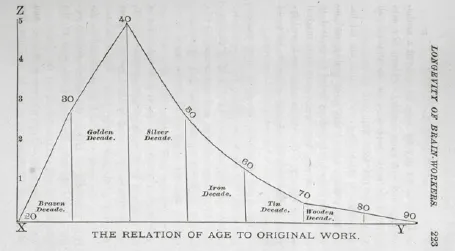

Jaques may have been the first to popularize the term, but his conceptualization of the midlife crisis was hardly new. Popular culture has long held that men, in particular, tend to experience, around the age of forty, what the French call le démon de midi. That psychologists have repeatedly sought to quarantine this demon is hardly surprising. In 1881 the neurologist George Miller Beard, the man who coined the term ‘neurasthenia’, published American Nervousness, written as a sequel to his previous study of nervous exhaustion. In it, he included a chapter on the ‘longevity of brain workers and the relation of age to work’, surveying 750 of the most eminent names in history as well as a series of less prominent figures. With quasi-mathematical certainty, he concludes that ‘the year of maximum productiveness is thirty-nine’. Creativity, for Beard, is a young man’s game: ‘the essence of poetry is creative thought, and old age is unable to think.’2 On this basis, he even awards medals to the passing decades: the thirties are the golden years, the forties the silver decade, and so on all the way to the wooden spoon of the seventies and eighties. Beard’s neurasthenic vision of ageing thus reverses the hierarchy of value traditionally ascribed to wedding anniversaries; the older we get – the further we drift from the golden mean of the middle – the less valuable we become. We walk up our 39 steps, and then we start walking down them again.

‘The relation of age to original work’, a diagram from George Miller Beard’s book American Nervousness (1881).

Unsurprisingly, subsequent psychologists sought ways of reversing Beard’s law of diminishing returns. Even before Walter Pitkin published his best-selling self-help book Life Begins at Forty (1932), his colleague G. Stanley Hall had made the point more seriously.3 In a study of 1922 entitled Senescence: The Last Half of Life (intended as a sequel to his study Adolescence of 1904), Hall coined the term ‘middle age crisis’, which he defined as a ‘meridional mental fever’ that afflicts men in their thirties and forties.4 Hall views this crisis, however, as marking the beginning of true maturity. ‘Modern man was not meant to do his best work before 40,’ he claims, before adding, in strikingly Nietzschean language, that ‘the coming superman will begin, not end, his real activity with the advent of the fourth decade.’5 Hall can retain such a positive view of middle age because he views it – to cite the title of his first chapter – as ‘the youth of old age’. Writing from the vantage point of his late seventies (born in 1846, he would die two years later, in 1924), Hall looks back wistfully to the supposed vitality of midlife: between adolescence and senescence, he implies, comes essence. It is all a question of perspective.

For another, far more celebrated psychoanalyst, middle age is the period in which ‘self-realization’ begins to take place. After falling out with Freud in 1912, Carl Jung underwent his own midlife crisis, rebelling against the tyranny of the unconscious and arguing that we in fact continue developing beyond childhood and into adulthood. Jung identified four stages of development, from childhood and youth to middle life and old age. The middle stage – which he famously calls ‘the second half of life’ – begins at around 35, and is characterized, in the healthy individual, by the attempt to find a ‘religious outlook’. By this, Jung means that we must gradually let go of our ego and learn to contemplate the meaning of the human condition: namely, that we develop towards death. Those who shrink from this acknowledgement fall ill – which is to say, they undergo a midlife crisis. In Jung’s words, ‘we cannot live the afternoon of life according to the programme of life’s morning.’6

If middle age is the period of self-realization, however, it is also the period of self-help. Search for the words ‘Carl Jung four stages of life’ on the Internet, and countless mindfulness, consciousness and personal development websites scroll invitingly down the screen. Jung even gives alternative names to his four stages – the ‘athlete’, the ‘warrior’, the ‘statement’ and the ‘spirit’ – implying a developmental relationship between them: we (should seek to) evolve from one stage to the next. The ‘statement’ stage – becoming a parent, losing a parent, reaching maturity – corresponds to middle age and its ‘psychology of the afternoon’; its implied sense of stock-taking reflects the increasingly ‘religious’ attitude that Jung would have us assume as we grow older.7 Although it is supposed to turn us away from our own concerns towards those of others, in encouraging selflessness this attitude still foregrounds the self as the measure of all things. Know thyself, in the words of the Delphic dictum – but especially in middle age.

As Jaques notes, though, there is a paradox not just in the conceptualization, but in the timing of this selfless self-realization. For, viewed from a more positive perspective, middle age is also the very zenith of our life, the period in which we come into our full powers of experience and maturity. Why should we be unhappy in the prime of our lives? The answer, of course, is that this prime is now end-stopped, or more precisely that we now realize that it is end-stopped. Jaques quotes the spatial allegory outlined by a patient in his mid-thirties: ‘Up till now . . . life has seemed an endless upward slope, with nothing but the distant horizon in view. Now suddenly I seem to have reached the crest of the hill, and there stretching ahead is the downward slope with the end of the road in sight.’ The summit, in other words, is also the start of the descent.

Jaques’s patient exemplifies the problems we all face as we reach middle age. Even for those of us who are not geniuses, the question of how not to ‘plateau’ takes on renewed significance. Success and a busy life are no defence against this; indeed, the more successful and active we are, the more we risk simply deferring the inevitable – and psychologically necessary – reckoning. In the words of the Italian poet Cesare Pavese, we do not free ourselves from something by avoiding it, but by living through it.8 Jaques quotes his patient as stating one day that his favourite slogan was ‘do or die’ – but that under analysis he now remembered he had always shortened it simply to ‘do’. In the prime of his life – the ‘time for doing’, in Jaques’s words – the patient functioned by convincing himself, even into his very motivational slogans, that death was to be denied.

Defined in these terms, having a midlife crisis might seem to be a very ‘first world’ problem, a modern luxury made possible by the spread of the bourgeois Western lifestyle. The peasants and subsistence farmers of the Dark Ages had more pressing things to worry about, one imagines, than whether they were going grey. Did they even live long enough to enjoy a ‘middle’ age? We tend to think of the average lifespan as having expanded considerably with the advent of modern medicine, and this is indeed the case if one surveys all the population, including those who (used to) die young. If one considers only the intellectual classes, however, then once one factors out infant mortality rates the life of the educated man remains relatively consistent over the centuries. Consider, for instance, the following statistics:

Life expectancy of men throughout history9

| Date | Mean age | |

| Kings of Judah | 1000–6000 BC | 52 |

| Greek philosophers, poets and politicians | 450–150 BC | 68 |

| After 100 BC | 71.5 | |

| Roman philosophers, poets and politicians | 30 BC–AD 120 | 56.2 |

| Christian Church Fathers | AD 150–400 | 63.4 |

| Italian painters | 1300–1570 | 62.7 |

| Italian philosophers | 1300–1600 | 68.9 |

| Monks Roll of Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians | 1500–1640 | 67 |

| 1720–1800 | 62.8 | |

| 1800–1840 | 71.2 | |

| Lifespan at fifteen years | 1931 | 66.2 |

| 1951 | 68.9 | |

| 1981 | 72.0 |

While life-expectancy figures are notoriously volatile – it all depends on the sample size and sources – there is no doubt that those who survived into maturity have historically had a better chance of a long life than we might now think. By the late twentieth century, we had gained around ten years on the aggregate of previous millennia; by the early twenty-first century, we have gained the best part of another decade, with most estimates for life expectancy in the developed world hovering somewhere around eighty. From antiquity onwards, nonetheless, if you made it past childhood and into education you had a fair chance of reaching somewhere near the biblical three score years and ten (with the notable exception of the bloodthirsty Romans). By the Victorian period, moreover, life expectancy for males once they reached the age of five was well past seventy.10 Such figures belie the standard Hobbesian view of pre-twentieth-century life as n...

Table of contents

- Front cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prologue: The Incremental Inch

- 1 Crisis and Grief The Invention of Midlife

- 2 The Piggy In the Middle The Philosophy of Midlife

- 3 Halfway Up The Hill How to Begin in the Middle

- 4 A Room At The Back of the Shop Midlife Modesty

- 5 Getting On The Tragicomedy of Middle Age

- 6 Perpetual Incipience The Midlife Gap Year

- 7 Realism and Reality The ‘Middle Years’

- 8 ‘The Years That Walk Between’ Midlife Conversion

- 9 Lessons In Lessness Midlife Minimalism

- 10 From The Prime Of Life To Old Age How to Survive the Menopause

- 11 Streams Of Consciousness Middle Age in a New Millennium

- Epilogue: The End of the Middle

- References

- Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

- Photo Acknowledgements

- Index