This is a test

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Most science chronicles present a triumphant march through time, with revolutionary thinkers and their discoveries following in orderly progression. The truth, however, is somewhat different. Scientific Feuds is a collection of the most vicious battles among the greatest minds of our time. It features such contests as Huxley and Wilberforce's debate on Darwin's theory of evolution, Franklin and Wilkins' fight over the discovery of DNA, and the "War of Currents" between Tesla and Edison (which ended with Edison electrocuting dogs and horses in a vain attempt to discredit Tesla's work). From passionate competition to vindictive sniping, these rivalries prove that the world of science is far from cold and methodical.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Scientific Feuds by Joel Levy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

|  |

KELVIN

vs

LYELL, DARWIN,

HUXLEY, et al.

FEUDING PARTIES

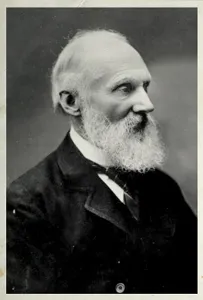

William Thomson, Lord Kelvin (1824–1907) – physicist, grand old man of British science

vs

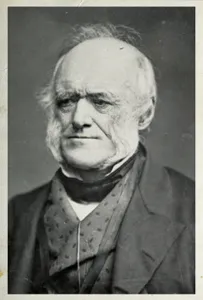

Sir Charles Lyell (1797–1875) – geologist;

Charles Darwin (1809–82) – naturalist;

T.H. Huxley (1825–95) – biologist;

and many others

DATE

1861–1904

CAUSE OF FEUD

Debate over the age of the Earth

Early scientists, including Newton, generally believed that the biblical account of the Creation was literally true, and therefore that the internal chronology of the Bible could be used to calculate the age of the Earth. Newton himself arrived at a figure of around 6,000 years but it was the Anglo–Irish Archbishop of Armagh, James Ussher, who, in a feat of formidable scholarship, determined that Creation began in the early hours of Sunday, 23 October 4004 BCE.

‘Incomprehensibly vast’

Ussher’s 1654 calculation remained the mainstream view until the 18th century saw the birth of a new science, geology – the study of how the earth was shaped. It became obvious to the practitioners of this nascent science that the processes and phenomena they observed must be acting on timescales much larger than the few millennia allowed by biblical literalism. The deposition of rocks, the uplift and folding of strata and mountains, the erosion of valleys and cliffs; all these spoke of slow processes operating over long periods. The emerging evidence of fossils, with their record of strange forms now vanished from the Earth, also suggested a long passage of time. Indeed, to geologists such as Charles Lyell, author of the seminal Principles of Geology, it seemed likely that natural processes of rock formation and erosion had been occurring for an effectively incalculable length of time; if not for a limitless period, certainly of the order of billions of years.

Meanwhile, another group of scientists was approaching the problem of the age of the Earth from a different angle. Naturalists were becoming increasingly convinced that species of plants and animals had changed over time through some form of evolution, but that this transformative process operated extremely slowly, and therefore constituted its own brand of evidence for the great age of the planet. The expanses of geological time opened up by Lyell were a key plank of Darwin’s argument in his 1859 publication On the Origin of Species, in which he cautioned: ‘He who can read Sir Charles Lyell’s grand work on the Principles of Geology and yet does not admit how incomprehensibly vast have been the past periods of time, may at once close this volume.’ To illustrate just how vast these periods had been, Darwin included a rough estimate he had made of the length of time it must have taken for the ocean to erode the Weald (a geological feature in the south-east of England), putting it at around 300 million years.

Lord Kelvin objects

To many at the time, such immense numbers seemed equivalent to eternity, and Lyell and, by extension, Darwin were seen as the standard-bearers of a school of geological thought called uniformitarianism. In its most extreme form, the uniformitarian view was that the Earth had effectively existed forever, and might well continue to do so, its geological processes endlessly cycling through the creation and destruction of landscape features. Lyell and Darwin did not subscribe to this extreme view, but they nonetheless became targets of the ire of a man who had proved that this theory of a never-ending cycle was impossible.

William Thomson, elevated to the peerage as Baron Kelvin of Largs in 1892 (the first scientist to be so honoured) and hence conventionally referred to as ‘Lord Kelvin’ or ‘Kelvin’, had elucidated, among other achievements, the laws of thermodynamics. Briefly stated, these meant that new energy could not be created out of nothing, and that the energy of any system would tend to dissipate. The laws meant that a perpetual-motion machine was impossible, and the endlessly recycling and eternal Earth of the extreme uniformitarians was effectively just that. Kelvin was having none of it.

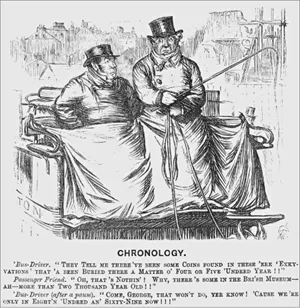

Chronological confusions. A cartoon from the satirical magazine Punch, from 1869, lampooning the use of the Bible as a basis for determining the age of the Earth.

In March 1862, Kelvin published a paper, ‘On the age of the sun’s heat’, in which he calculated that the Sun had been burning for less than a million years. ‘What then,’ he asked, ‘are we to think of such geological estimates as 300,000,000 years for the “denudation of the Weald”?’ Given that his estimate of the age of the Sun, though imprecise, was based on ‘known physical laws’ and was orders of magnitude less than the figure arrived at by Darwin, he suggested that it was probable that the naturalist had underestimated the speed of erosion that could be caused by ‘a stormy sea, with possibly channel tides of extreme violence’.

Kelvin was one of the world’s great authorities on the dynamics of heat. He started with several assumptions: that the Earth had begun as a ball of molten rock; that, in accordance with his laws of thermodynamics, no heat could have been added to the system since this formation; and that convection currents had allowed uniform cooling of this molten globe to a solid sphere of uniform temperature, which then radiated the rest of its heat out into space from its surface. It was widely known from mining that the ground got hotter as you went down, with a thermal gradient of about 1°F per 50 feet (0.5°C per 15 metres). Kelvin did his own experiments to determine the thermal conductivity of rocks, and employed his mastery of Fourier mathematics to work out how long it must have taken for the planet to cool to its current temperature. He arrived at an estimate of 98 million years, with a range of 20–400 million years for the highest and lowest possible figures.

Burned fingers

Kelvin’s calculation carried enormous authority, thanks both to his eminence and to the manner in which he seemed to have applied ‘hard’ science and ‘pure’ mathematics to a field that had previously been the victim of woolly thinking. The mature and respectable science of physics had set straight the immature new discipline of geology. Darwin was chastened; he considered the age limit that Kelvin had placed on the Earth to be the most serious and credible argument against his carefully worked out theory, which demanded immense epochs of time. The scientist Fleeming Jenkin summarized the argument: ‘The estimates of geologists must yield before the more accurate methods of computation, and these show that our world cannot have been habitable for more than an infinitely insufficient period for the execution of the Darwinian transmutation.’ Darwin himself referred to Kelvin as his ‘sorest trouble’ and an ‘odious spectre’.

TIMELINE

Darwin was so troubled that in the third edition of On The Origin of Species he removed his Weald calculation altogether, but even this did not quiet the criticism from Kelvin and his allies. In April 1869, Darwin was moved to warn Lyell theatrically: ‘Having burned my fingers so consumedly with the Wealden, I am fearful for you ... for heaven’s sake take care of your fingers: to burn them severely, as I have done, is very unpleasant.’

‘The grandest mill’

Darwin may have been running scared, but his self-appointed bulldog, T.H. (Thomas Henry) Huxley (see pages 38–47), was ever ready to take up the gauntlet on his behalf. In his 1869 presidential address to the Geological Society of London, Huxley defended the views of the ‘old Earthers’ and pointed out the basic flaw in Kelvin’s approach: ‘Mathematics may be compared to a mill of exquisite workmanship, which grinds your stuff to any degree of fineness; but, nevertheless, what you get out depends on what you put in; and as the grandest mill in the world will not extract wheat flour from peas cods, so pages of formulae will not get a definite result out of loose data.’ In other words, Kelvin’s calculations might be unimpeachable, but if he had got his starting assumptions wrong then his conclusions would also be wrong.

The scientific world now began to gather behind the respective banners of Kelvin and Huxley. And although the physicist P.G. Tait used a new method to calculate that the Sun was around 20 million years old and the Earth only 10 million, in the tenth edition of his Principles of Geology, Lyell accepted that the age of the Earth was finite but dated the Cambrian era to around 240 million years ago. Although many scientists sought some middle ground, attempting to prove that evolutionary and geological processes might act relatively quickly, operating within Kelvin’s timescale, it was becoming increasingly obvious that both sides could not be correct; someone must be making basic errors.

The geophysicist Osmond Fisher suggested that the error was Kelvin’s, proposing a new (and prescient) model of the structure of the Earth – a thin crust over a plastic substratum – that would destroy the basic assumptions upon which Kelvin had based his calculations. Fisher further pointed out that it was a form of scientific arrogance to disregard the clear evidence of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: Earth Sciences

- Part Two: Evolution and Palaeobiology

- Part Three: Biology and Medicine

- Part Four: Physics, Astronomy and Maths

- Glossary

- References

- Index

- Acknowledgements

- Features