■ What is a Documentary?

Documentary as a form has many points of origin. Some people look to Robert Flaherty’s footage of Inuit life in Northern Canada in Nanook of the North (1922), others to works by Dziga Vertov and his innovative portrait of urban life in the new Soviet Union in Man with a Movie Camera (1929). For many others, the edifying documentaries of the 1930s British documentary movement, described by founder John Grierson as a “creative treatment of actuality,”1 still serve as defining models for today’s documentarians. Wherever we locate its origins, at its most basic, documentary film offers us some kind of vision of how the real world looks and operates. Documentary filmmaking is a fascinating pursuit because it allows us to comment on our society, offers us a glimpse of other ones, and may even exhort our audiences to change the world we live in. As we will explore in this chapter, documentary makers use a wide variety of elements including interviews, records made while historical events unfold, archives of sound and image, and even actors to offer viewers something that is both non-fiction and a story.

As we will see in the coming chapters, “documentary” describes a whole field of filmmaking, from educational films to activist ones, from hard-hitting video journalism to lyrical poetic expressions. But every documentary starts with an idea not just about the real world, but about the process of representing reality as well.

■ Where Do Documentary Ideas Come From?

All documentaries start with a moment of insight, with somebody (usually the producer or director) realizing that a particular person, subject, or event would make a great non-fiction film. That “aha!” moment is the beginning of months, or often years, of work. Sometimes it’s a question that won’t let go of you until you explore it more deeply.

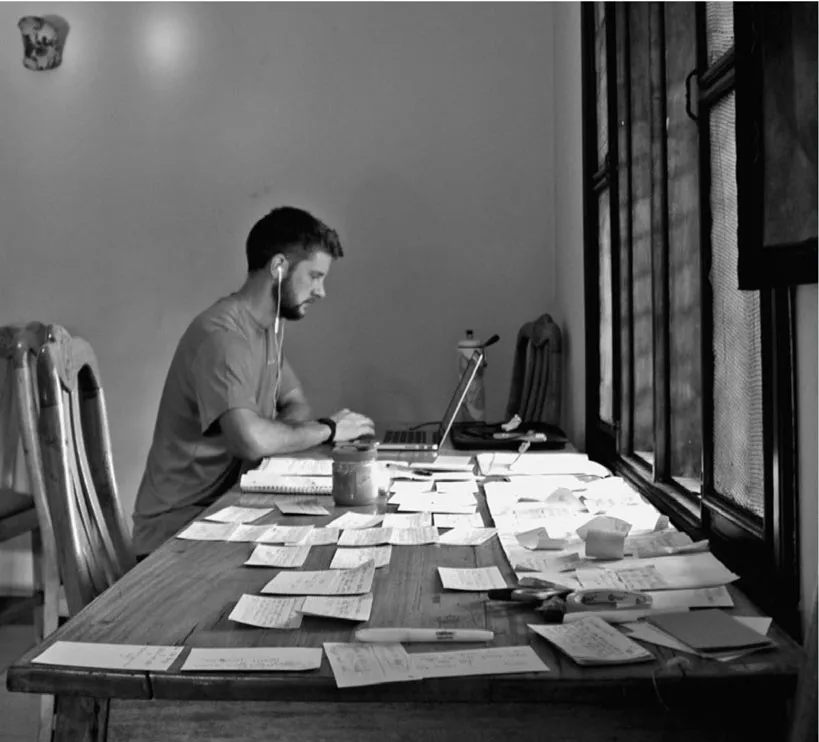

For one of our students, Nathan Fitch, that moment came a few months into his time in the Peace Corps. He was working on the tiny Pacific island of Kosrae, part of the Micronesian archipelago. He recounts:

I visited a remote village with several of my fellow volunteers. As I trudged through the hot sand, I saw a man seated in the shade of a coconut palm. He was wearing camouflage fatigues. Eager to test out my burgeoning language skills, I accosted him in the local language, “Len wo. Kom fuhka?” (Good day. How are you?). He squinted up at me, then replied in English flavored with a Southern drawl. “Hey man, I’m doing good. How are y’all making out?” I was shocked, for few of the young people I had met were confident speaking English—especially to a stranger.

I asked the man, “Have you lived in the US?” “Yes sir,” the man replied, “I’ve been in Fort Benning and Fort Carson. Just got back from Iraq a few days ago for some R&R.” “Iraq?” I confirmed. The man nodded. “Yep, stationed right outside of Baghdad. I’m heading back there next week.”

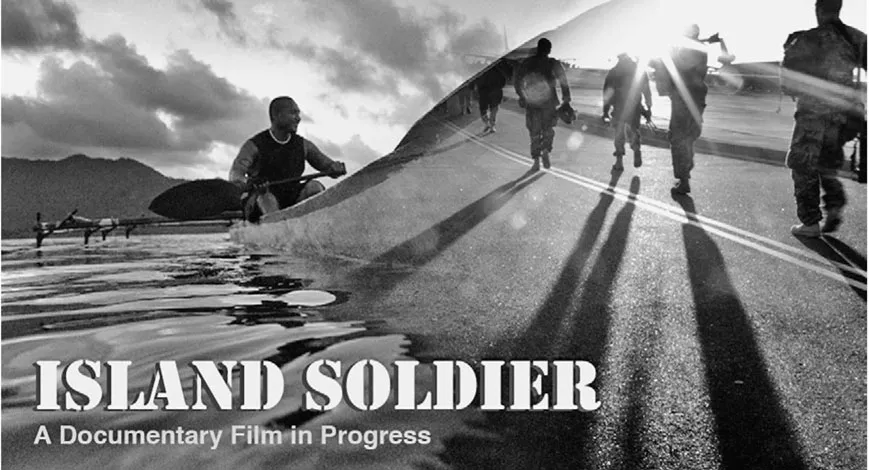

There were many things I might have asked this soldier had I lingered longer, a cascade of questions that would have highlighted my ignorance of the geopolitics of the region that I now called home. Questions like, “Why are you fighting for the US in Iraq, when I, a US citizen, am not?” “What is it like to leave such a peaceful place for the turmoil of war?” “What is it like to return?” It was these questions, and the somewhat guilty understanding that he was serving in my place so that I could be in the Peace Corps, that were the impetus for my documentary Island Soldier (Figure 1.3).3

■ Are Documentary Filmmakers Artists?

In a 2014 essay “Reflections on Getting Real: Debunking Five Myths That Divide Us,” documentary filmmakers Pamela Yates and Paco de Onís write about the common misperception that filmmakers who tackle human rights abuses, or illuminate social issues, are not artists:

We give equal weight to being artists as well as human rights defenders. We know that as we get better and better as artists, we create wider audiences with far greater impact. Because we aren’t just developing a narrative story arc, we are developing ideas across the length and breadth of the documentary film. It’s the interplay of the two that creates dramatic tension. The power and beauty of cinema are our artistic and political tools. Our canvas is global; our palette, the human condition.2

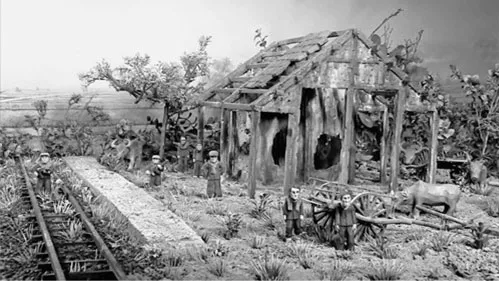

■ Figure 1.1 Rithy Panh uses clay figures, archival footage, and his narration to recreate the atrocities Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge committed between 1975 and 1979 in The Missing Picture.

One only has to look at a documentary like Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture (2013), about the Cambodian genocide, or Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir (2008), about the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, to see the incredible range of creative practices that documentary filmmakers are using to tell stories about real-life events (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). While documentaries like these redefine the genre through their nontraditional use of animation, even more traditional approaches have extensive creative dimensions that overlap with those of fiction film, theater, photography, painting, and even music.

■ Figure 1.2 Animation provides compelling visuals for Waltz with Bashir while recreating the traumatic psychological experiences of veterans of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon.

Every documentary filmmaker has their own process for finding the seeds of a good film. And like most people involved in creative endeavors, many experience self-doubt and some anxiety about their ability to come up with a good topic and stick with it. It can be reassuring to remember, as choreographer Twyla Tharp puts it, that “there are no creative geniuses . . . in order to be creative, you have to know how to prepare to be creative.”4 Many people report that breakthrough ideas came while they were cleaning the house, taking a shower, or out for a walk. But these moments of creative breakthrough can only come when combined with everyday practices that pave the way. For documentary filmmakers, this often means keeping track of the people, social patterns, trends, and events that are occurring in our communities, country, or world. Many have rituals that include things like keeping a journal, clipping (or, increasingly “bookmarking”) articles from newspapers, magazines, or blogs they read every day. As Graeme Sullivan suggests, “art practice can be seen as a form of intellectual and imaginative inquiry, and as a place where research can be carried out that is robust enough to yield reliable insights that are well grounded and culturally relevant.”5 Other rituals keep filmmakers in touch with their creative potential. Filmmaker Luis Buñuel, for example, committed to having coffee with one particular producer every day, and to telling him a story. While not every story was worthwhile, the practice of coming up with a story a day to tell his producer created enough good ideas that Buñuel was able to make at least a movie a year for most of his working life.6 The important thing is that you create a routine that works for you, and that you follow it consistently.

■ Figure 1.3 Nathan Fitch’s film Island Soldier (2016) started from a chance encounter on a small Micronesian Island.

In addition to being curious, documentary filmmakers tend to be passionate and interested in communicating their ideas and experiences to others. Jay Rosenstein, the director of In Whose Honor? (1997), about the controversy around the use of Native American mascots in sports, recounts the moment he realized he needed to make a documentary about the topic (Figure 1.4):

■ Figure 1.4 Charlene Teters, a Spokane Indian woman whose activism sparked Jay Rosenstein’s interest in the use of Native American mascots in sports. Her story became the centerpiece of In Whose Honor?

I heard this woman, Charlene Teters, speak. She is a Spokane Indian, and she was talking about the University of Illinois mascot Chief Illiniwek (Chief Illiniwek is a pretend Indian that dances at football and basketball games). I had never heard an Indian person talk about the mascot. I was kind of stunned, and very moved, and I thought “Everybody needs to hear this.” And so the film became a way for me to try to get Charlene’s voice and her message out to people who couldn’t or wouldn’t otherwise hear it. So sometimes you just learn information that isn’t known, that you think should be known, and you become passionate about spreading those ideas.8

Other filmmakers use the process of making documentaries to better understand their world. When he began the film that would eventually become The Thin Blue Line (1988), director Errol Morris was making a documentary about Dr. James Grigson, a Dallas psychiatrist who had testified for the prosecution in many

in practice

Paving the Way for Creativity

On a trip through Europe, video artist Edin Velez came up with a ritual that ultimately helped him conceive of an idea that would define his work for decades to come. He decided to create a collage journal as a way of testing out different ways of layering images in a single frame (Figure 1.5).

For me, creating small works, not necessarily in your primary medium, is one of the best ways to tap into creativity. It’s always nice to set up a certain number of rules, because if it’s too open people tend to flounder. So I decided that each page had to be finished before I left the location I was in, and I could only use photographs I took or other things I found in that location. It was very freeing to make the journal, because unlike making a video, where you’re concerned about showing it to people, this was a very personal book and I didn’t expect to show it to anybody. The beauty of allowing yourself moments to explore is that out of all this you will have ideas that will be cheesy, and ideas that make you cringe, but then you will have great ideas you never expected to have. You are focusing on the simple task of cutting and gluing images, but what you are really doing is placing your mind in that creative zone. It puts the mind in a place where it allows concepts and ideas to flow from unconscious to conscious.7

■ Figure 1.5 Using small exercises to stimulate creativity. Filmmaker Edin Velez’s collages (left) helped him develop the ideas about image layering that were later incorporated into his video work. The still frame on the top right is from his highly layered film about the traditional and the contemporary in Japanese culture, The Meaning of the Interval (1987). At bottom right is a frame from Dance of Darkness (1989).

death penalty cases. Along the way, Morris interviewed Randall Adams, one of the “cold-blooded killers” (Grigson’s words) that Grigson had helped put on death row, and his film took a completely different turn. He explains:

As I read about Adams’ story I slowly but surely became convinced that there had been a terrible miscarriage of justice. And then the movie changed. It was no ...