![]()

← 10 | 11 →

PART I

Portrait of a Dictator

← 11 | 12 →

![]()

← 12 | 13 →

ANGIE EPIFANO

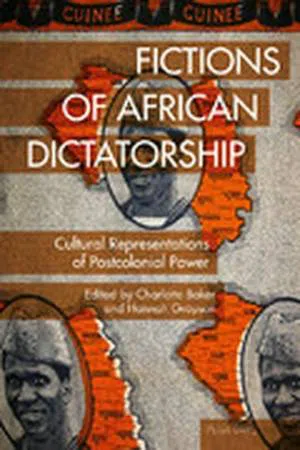

1 The Image of Sékou Touré: Art and the Making of Postcolonial Guinea1

From outward appearances, President Touré is the living national hero for Guineans. He supposedly knows everything and everything stems from him and passes through him. He sets the standards.

— LANSINÉ KABA, 1981, p. 53

Le Responsable Suprême de la Révolution [The Supreme Leader of the Revolution], Silly, Le Commandant en Chef des forces armées populaires et révolutionnaires [The Commander in Chief of the Popular and Revolutionary Armed Forces], Le Président [President] – are just a few of the many titles that Sékou Touré (1922–1984) earned during his lifetime.2 Often described as one of the most charismatic men in modern history, Touré was the lifeblood of the Guinean independence movement and postcolonial government.3 Touré manipulated every aspect of Guinean ← 13 | 14 → life to be a perfect reflection of his ideologies and fabricated persona. He imagined postcolonial Guinea as a direct descendent of the precolonial Wassoulou Empire, ruled by Samory Touré (c. 1830 to 1900), and articulated a desire to regain this empire’s lost power.4

A body of remarkable photographs produced throughout Touré’s reign illustrates his endeavours to transcend the boundaries of time and space, appropriating past glories for his present aims. These photographs of Guinean citizens and material culture, ranging from clothing to festivals to streetscapes, collectively reveal the dictator’s strategic manipulation of the country, and form the basis for analysis here. As this chapter will demonstrate, at the heart of Touré’s power was his ability to craft, perform, and maintain a cohesive cultural narrative that united the new nation. This chapter examines this body of material in order to understand how photographs affected the development of nationalism in this West African state. I argue that the essence of Guinean identity became the image of, and mythology surrounding, President Touré.5 National ideology was visually circulated through public displays of portraits of Touré and coded allusions to his persona.6 This circulation contributed to a metonymic relationship in which Touré stood in for the Guinean people and nation, ← 14 | 15 → while the Guinean people also stood for Touré himself and his vision of the new nation.

From the earliest existence of the colony, Guinea was a thorn in the side of French colonial authorities, which constantly struggled to maintain peace and order in the seemingly lawless colony.7 French governors and military officials in the late nineteenth century repeatedly discussed the difficulties at maintaining peace in Guinea. The colony was one of the last to be officially pacified, in 1898, and even after this point insurrections continued to break out for several decades. The most notorious of these insurrections was led by the Peul leader, Alfa Yaya of Labé, who continued to fight the French into the late 1910s. The Guinean hero Almamy Samory Touré was the most famous nineteenth-century revolutionary, and today is considered to exemplify Guinea’s fierce sense of independence.8 Samory Touré founded, presided over, and defended the last African-ruled empire in precolonial Guinea, the Wassoulou Empire.9 He is internationally viewed as one of the greatest heroes of West Africa, but is especially important to the people of Guinea and his visage dots Conakry to this day. The story of Samory exists in an ambiguous realm between fact and fiction; his accomplishments and origins continue to be reimagined and elaborated upon to this day. The publication of a 1963 American children’s book exemplifies the dissemination of narratives about the Almamy on an international scale. Although written in English and sold in the United States, the story is based on research that was financially supported by Sékou Touré’s regime.10 ← 15 | 16 →

As the story goes, Samory was born in 1830 to ‘humble beginnings’ in Bissandugu, Guinea.11 By the age of thirteen, he was already widely renowned for his ‘military skills, regal bearing, and splendid physique,’ and quickly rose to power.12 From the 1860s onward, Samory steadily began to gain control of more land, wealth, and people, and ‘founded’ the Wassoulou Empire – the first and last independent Malinké kingdom in West Africa.13 During this period, the French annexed ‘Guinea’ and placed the region under their control.14 The French first encountered Samory in the late 1870s, yet the two sides did not come into conflict with one another until 1881 when the French ordered Samory to leave several key ports on the Niger River.15 For the next seventeen years, conflict reigned in Guinea.16 Samory’s army held out until 1898 when they were finally defeated. Samory himself was captured and exiled to Gabon, where he died under contentious circumstances in 1900.17

The tale of Samory marked the beginning of a power struggle between Guinea and France that lasted for decades, which eventually came to a head ← 16 | 17 → with the famous ‘Vote for No’ campaign.18 In 1958, French president Charles de Gaulle attempted to reaffirm African colonies’ commitment to the French state by calling an election across French West Africa that would determine whether colonies would remain connected to France or would leave the empire. African voters were given two options: yes, remain part of the empire, or, no, leave the empire. On 28 September 1958, Guinea shocked the world by becoming the first French colony to declare independence.19 The French withdrew from Guinea, and in the process, destroyed a large portion of the infrastructure in and around Guinea’s largest cities. In the following months, the charismatic politician Sékou Touré was elected president. His political party, the Parti démocratique de Guinée [PDG, Democratic Party of Guinea], consolidated power and declared itself the only party in the new République de Guinée [Republic of Guinea].20 Touré and the PDG faced the monumental role of simultaneously uniting the nation, maintaining a balance of power between ethnic groups, and validating their nation’s right to exist on a global scale.21 These difficulties bore heavily upon the country and contributed to Touré’s formation of an autocratic dictatorship. Although Touré’s policies were far from liberatory they were perceived as necessary to ensure that Guinea would survive and thrive. Guinea’s complex history shaped Touré’s political decisions, which affected national cultural policies, which, in turn, further influenced Touré’s politics.22

After gaining independence, almost overnight Guinea became an extension of Touré himself. National cultural policies were enforced that monitored and controlled art making and consolidated creative thought into Touré’s hands.23 These policies were Touré’s brainchildren that were implemented ← 17 | 18 → by government agents and other politicians. He used these policies to reify Samory and vilify the French. For Touré, this endeavour was of utmost importance. Its gravity is best exemplified in the 1968 national cultural festivities honouring ten years of Guinean independence. After weeks of celebrations revolving around Samory and the Wassoulou Empire, the dénouement of these activities comprised a series of ceremonies marking the return of Samory’s remains to Guinea.24 This monumental event was at the heart of Sékou Touré’s identity as a ruler and desired identity for Guinea itself. From the start of his rule, Touré had maintained that he was a direct descendent of Samory. Later, Touré would go so far as to claim to be the reincarnation of Samory.25 This physical connection allowed Touré to place postcolonial Guinea within a lineage of African independence fighters, thereby shoring up his own validity and that of the nation.26 The narrative was transformed into a communal history that bypassed ethnic differences and concretely defined the Guinean people and a Guinean identity.27 Over the following decades, Touré used the image of Samory to visualize Guinea as an extension of the Wassoulou Empire, with himself as the Samory-like nucleus.28

Cities and villages were encoded with visual and textual references to Touré, making it impossible to escape his image. Touré’s daily outfit of stunningly white slacks, a short-sleeved shirt, and a somewhat boxy hat became so famous that the hat itself is now simply called a ‘Touré hat’ (Figure 1).29 These sartorial choices were reminiscent of Samory’s own ← 18 | 19 → costuming, and linked the two men through time. Touré’s fame was not produced by mistake, but was part of the leader’s carefully crafted agenda of decolonizing, modernizing, and uniting Guinea. After the mayhem caused by France’s violent withdrawal from the country, Touré recognized that Guinea’s success as a nation necessitated unity. In order for this to happen, Guineans had to put aside ethnic differences and begin defining themselves first as Guinean. This proposal necessitated the implementation of a national cultural system that would create ‘horizontal comradeship’ between ethnic groups.30

Figure 1: Photograph from Festivals Culturels Nationaux, page 112. Caption reads, ‘Le President Ahmed Sékou Touré et son hôte de marque au Palais du Peuple.’

Between 1959 and 1961, Touré implemented a ‘demystification’ programme that was ostensibly meant to ‘civilize’ the rural population by rooting out ← 19 | 20 → ‘detrimental’ cultural practices.31 The PDG described demystification using positive language that focused on the ‘backward’ and divisive nature of non-Western cultural practices.32 Further, the PDG claimed that there would be economic benefits to demystification, since the programme would theoretically modernize the country and eventually foster international trade partnerships.33 In reality, demystification was an iconoclastic movement that destroyed an untold number of objects and eradicated centuries-old traditions.34 As part of demystification, Guinean soldiers were deployed across the country, where they destroyed ‘pagan’ material culture and forcibly converted entire villages to either Islam or Christianity.35 The final deathblow to polytheism and traditional arts was a law passed circa 1959 that made it illegal for Guineans to practise any ‘discriminatory cultural development.’36 It was specifically aimed at outlawing any custom that was determined to be unique to a specific ethnic group – activities deemed ‘individualistic,’ anti-Guinean, and detrimental to the nation itself.37 A wide range of activities were made illegal, including the carving of masks, the production of ethnically relative literature, and the practising of polytheistic religions. Along with demystification, this law led to the near eradi...