![]()

1

The Meaning of Work in Women’s Lives

Dotha Bushnell lived on a Connecticut farm in the early 1800s, among the last of generations of American women who worked in households that produced all the necessities of survival. Her son, Horace, lamenting the disappearing past, wept over the “frugal, faithful, pious housewife” who lived in an age when “the house was a factory on the farm; the farm a grower and producer for the house.” All of a household’s members were harnessed together “into the producing process, young, old, male and female, from the boy that rode the plough horse to the grandmother knitting under her spectacles.”1

Nobody then or now could wonder if Dotha Bushnell worked. Whether she was an enslaved woman who worked in the fields, or an indentured servant or the mistress of a plantation household, a woman had a job to do. In preindustrial societies, nearly everybody worked, and almost nobody worked for wages. But with industrialization, the harness yoking household members together loosened. As production began to move out of the household into factories, offices, and stores, those who got paid for the new jobs were clearly workers. At the same time, the kinds of work women did at home changed dramatically. The remaining tasks of the household, such as caring for children, preparing food, cleaning, and laundering, were not so clearly defined as work. In separating the jobs necessary to maintain the household from the jobs done for pay, the Industrial Revolution effected not only a shift in the tasks assigned to workers of both sexes, but a shift in perceptions of what constituted work for each. Women who maintained the home and did not collect wages were no longer identified as workers. Their home roles seemed shaped by love, or commitment, simply the natural product of biological difference. We might consider whether, in our new postindustrial or information society, as the tasks of men and women once again converge, perceptions of what constitutes work have once again changed.

In the preindustrial period, almost everyone did what could, in one sense, be called domestic work. As servants, slaves, or family members, their tasks revolved around the household, which constituted the center of production. Among family members, women as well as men derived identity, self-esteem, and a sense of order from their household places. For the enslaved and servants, whose work lives centered in other people’s families, household tasks were nevertheless the source of survival. For the most part, the core family and its extended members consumed the goods and food produced in this unit, trading what little there was left to make up for shortages.

There seems to have been a rhythm to the work performed in this pre-industrial environment, in harmony with the seasons in the countryside and with family needs in both town and country. By the sixteenth century, much of Europe had what we would now call an unemployment problem: too many workers and too few jobs. To feed, clothe, and shelter the population at minimal levels required fewer workers than the numbers of people available. As a result, work was spread out. The evidence suggests that traditional role divisions—which assigned to women internal household tasks and care of gardens, dairies, and domestic animals, as well as small children—allowed men a good deal more freedom than their wives. Men, more than women, benefited from a growing labor surplus. Women’s tasks tended to be less seasonal and more regular. Over the span of a year, men had fewer onerous and regular responsibilities.2

In the pre-revolutionary period, everyone did what could, in some sense, be called domestic work. This drawing depicts life around 1776. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

The transition from this relatively self-sufficient domestic economy to dependence on trade took hundreds of years and developed at different speeds in different areas. The first inroads occurred when the commercial revolution of the thirteenth century created a market for manufactured goods and encouraged craftsmen and their families to concentrate their energies on producing for cash. Artisan families, who had previously made and sold their own products, began to produce for merchants who bought in bulk and sold to distant places. In these family industries, women, who were generally excluded from formal apprenticeships, could nevertheless become skilled craftworkers by ‘stealing’ the trade from male family members. They were partners in every sense of the word. Women cooked and laundered for apprentices; they performed some of the tasks of production; in most places the law acknowledged a wife’s right to the business if a husband died. The garden plot still produced food supplies, and wives and widows supervised and trained young unmarried women to perform household work. If labor within these artisan families seemed relatively balanced, it was far from idyllic. Work within the household, in the shop, and on the farm was always hard. Poor crop yields or sickness could bring even comfortable households to the edge of starvation.

As trade developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a subtle change came over family industry. Merchants, who had at first been content to take what was available and sell it, soon began to demand products made to their own specifications. Instead of gathering the products of local artisans, they “put out” their own orders to cottages throughout the countryside. Workers lost control over what they made. They still retained control over their time. People who worked in their own cottages would not be rushed. They did more or less work as other tasks called, and sometimes they wasted materials. As orders increased, however, merchants required faster and more reliable production. Effective supervision of workers could be obtained only if the labor force were concentrated in one place. And toward the end of the eighteenth century, the development of steam-powered machinery required a labor force able to move where the machines were, adding urgency to the demand for a factory workforce.

Slowly and painfully the laboring poor were persuaded to give up their own loosely jointed and self-imposed definitions of work. In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England, land that had been held in common for generations, as well as some that had traditionally been leased by families, was taken over by large landowners for their own use. This process, called enclosure, meant that some farm families were forcibly ejected while others no longer had common pasture. Ultimately, they could not survive on the land. Driving men, women, and children from farms made them available for work in towns. But they were reluctant workers. Employers could persuade them to show up for work regularly only by holding back wages or tying them to contracts that ran for as long as twenty-one years. Sometimes employers beat inattentive workers, especially children. Frequently the state passed laws to help employers create a reliable workforce. In England and France, harsh laws against vagrancy forced people to take jobs against their own inclinations. Those who would not submit might be branded or jailed and later deported to colonies in far-off places.

Work in the Colonies

As in the old world, workers in the American colonies did not easily submit to the idea of working by someone else’s rhythms. The Spanish who colonized parts of the South and Southwest discovered that Native Americans would not willingly perform manual labor for them. In early Virginia, developing a work rhythm proved to be a special problem. Historian Edmund Morgan describes how Virginia’s first colonists starved rather than bow to what they saw as the harsh discipline of the Virginia Company. They chose to work only six to eight hours a day, spending the rest of their time “bowling in the streets.” These work patterns, reminiscent of English habits, lasted until the Virginia Company imposed a quasi-military regime.3

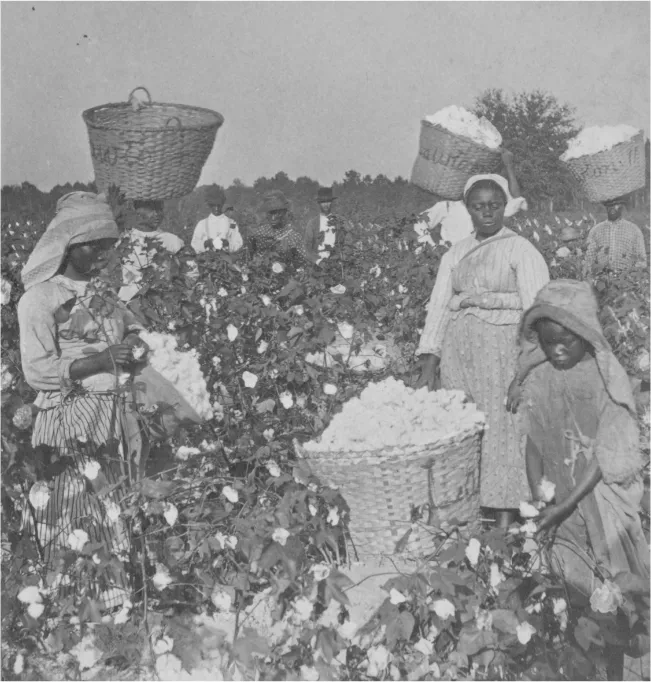

The tasks of enslaved women varied, but picking cotton was one of the most typical things she might do. (Photographs and Print Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations)

The northern colonists required less pressure. Because their land was not owned by an outside company, and because many of them had come to America for common religious reasons, most early New Englanders shared an incentive to work. Puritan religion equated hard work with godliness, and salvation with the visible demonstration of God’s bounty, so New England colonists drove themselves to accumulate earthly goods. Material reality enforced religious injunction. Unlike Virginia settlers, in their early years the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonists had no company in England to call on for supplies. Throughout the colonial period, they suffered from severe labor shortages that only their own efforts could offset. And lacking appropriate raw materials to trade with England, they relied far more on homespun yarn and hand-woven fabrics than the southern colonies, which quickly developed tobacco and hemp as resources for trading.

Since all the colonies relied more or less on household production, women’s work was necessary and recognized. Early on, northern as well as southern colonies learned to rely on enslaved women and indentured servants for services to the household, and agricultural labor. Enslaved women who produced children who were themselves enslaved provided a cruel, but valuable service.4 White women received somewhat better treatment. Colonies initially gave plots of land to female settlers and their families. In Maryland and South Carolina, women who were heads of families received allotments equal to those of men. For a few brief years, Salem gave “maid lots” to unmarried women, and Pennsylvania granted them seventy-five acres each. But opposition to unmarried women holding land developed early. Historian Julia Spruill cites a bill passed by the Maryland Assembly in 1634, and then vetoed by the proprietor. The legislators would have decreed of an unmarried woman that “unlesse she marry within seven years after land shall fall to hir, she must either dispose away of hir land, or else she shall forfeit it to the next of kinne, and if she have but one Mannor, whereas she cannot alienate it, it is gonne unless she git a husband.”5

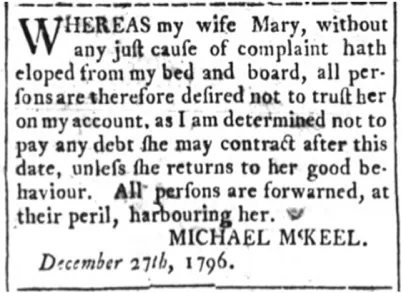

Without land, women had no source of sustenance except employment or marriage. Fearful that the unmarried would become dependent, colonies quickly passed laws that bound people who had no visible means of support out to work. Women, it was thought, were especially prone to vice and immorality, and colonies as different as Massachusetts and Virginia paid special attention to those women who, having no homes in the conventional sense, might fall into bad habits.6 Harsh economic considerations undoubtedly motivated the colonists. Since pregnancy was a likely result of immorality, and there were few jobs for unwed mothers with small children, such women were likely to need public relief. Afraid of the potential costs, communities were especially careful to refuse female transients permission to settle.7 An unhappy wife who left her husband might find herself repudiated by him. Husbands were often less interested in their wives’ return than in shedding economic responsibility for them.

A wife who no longer served her husband would typically be repudiated.

The assumption that women could and should participate in the production of necessary goods persisted well into the eighteenth century, and in many areas even later. When the colonists became concerned about having adequate supplies of cloth and yarn in the revolutionary period, they appealed to women’s patriotic sentiments to increase supplies. George Washington wrote to his friend the Marquis de Lafayette that he would not force the introduction of manufactures to the prejudice of agriculture. But, he added, “I conceive much might be done in the way of women, children, and others without taking one really necessary hand from tilling the earth.”8

In contrast to much of Europe, where the imposition of work discipline required breaking old habits, in America colonists had already accepted an emphasis on work and industry before the onset of industrialization. This eased the task of disciplining a labor force for factory work. Where the Puritans had seen material prosperity as a demonstration of God’s grace, the people of the early nineteenth century saw it as a manifestation of self control and right living. Religious injunction was thus supplemented by new ideas of individualism that made each person accountable for his or her success. Egalitarian notions that had emerged in the revolutionary period enhanced these ideas. Theoretically, at least, success was now plausible for even the lowliest people, slaves, people of color, and women excepted. Benjamin Franklin, who saw wealth as its own reward, urged people to depend “chiefly on two words: industry and frugality; that is waste neither time nor money, but make the best of both.”9

The Success Ethic

The emphasis on individual achievement inherent in an ideology that glorified success threatened to eliminate entirely the older notion that individual well-being was intimately bound to the progress of the community. It was one thing to spin and weave for the public good and to reap material rewards incidentally. It was quite another to work for others for the sake of their profit alone. By the time Andrew Jackson became president of the United States in 1829, it seemed clear that those workers who could afford to own a small shop or a piece of land valued entrepreneurship over working for wages.

In this respect, white American workers had some advantages over workers in older European societies. Relatively cheap, available land encouraged free workers to save money and move west. Employers were willing to let them go because a steady influx of immigrants in the North, and an expansion of slavery in the South, replaced them. For free workers, the promise of independence and of upward mobility provided incentives to work hard. For the enslaved, increasing coercion, the threat of bodily harm, and the absence of realistic alternatives motivated reluctant cooperation. Yet these incentives did not always produce the kind of workforce employers felt they needed.

To integrate native- and foreign-born peasants, farmers, skilled artisans, and day laborers into an industrializing society required, as historian Herbert Gutman has pointed out, a continual process of acculturation. Each generation had to be taught to shed its old ...