![]()

BEGINNINGS

Early Life and First Stories

Bester's story as an outsider writer, perhaps not surprisingly, began with the pedigree of an insider. In fact, he witnessed the birth of genre SF firsthand. Although only twelve years old at the time, he was “hungry for ideas” and searching for imaginative outlets suited to his curious turn of mind but struggling hard to find them. He even remembered borrowing Andrew Lang's Blue and Red fairy books from the library and sneaking them home under his coat, feeling self-conscious about reading fairy tales at his age.1 Then, in April 1926, the first issue of Hugo Gernsback's trailblazing Amazing Stories debuted on newsstands, and Bester's eyes opened wide. He would later characterize the emergence of the science fiction magazine as a major cultural event that was, in its own way, every bit “as revolutionary as the talkies” of the same era. No one who learned to read afterward, he once remarked, could fully understand “what a gap science fiction filled” for his generation, “what an imaginative need it answered.”2

In some respects, Bester's initial encounter with SF followed a common pattern, one documented anecdotally by a host of writers and fans over the years: he fell for SF hard and fast and young. However, his origins story differs instructively from those of other writers of roughly the same era, as the examples of Frederik Pohl and Damon Knight serve to demonstrate. On the one hand, a ten-year-old Pohl took just one look at the sensational art on the cover of a pulp magazine and saw in SF a form of escape from grim, Depression-era realities. On the other, Knight was drawn in by stories that extrapolated scientific trends into the future and stirred feelings of awe and wonder. Both Pohl and Knight characterized SF as an all-consuming addiction. Bester, by contrast, thought of SF as a gateway. He admired it for its ability to serve as an “agar for thought” and open up a larger “world of ideas.”3 Not long after he discovered SF, his nightstand was piled high with reading, not only an assortment of science fiction magazines but also books ranging from Sir Isaac Newton's Principia (1687) to Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls (1842) to Camille Flammarion's Mysterious Psychic Forces (1907) and well beyond. Bester cut his teeth on science fiction, as far as ideas went, and he would never forget the excitement of that moment or the importance of SF to his intellectual development.

Bester's outlook perhaps seems unremarkable, a variation of the commonplace notion of SF as a literature of ideas, but his understanding of the genre grew out of an early fixation on the Renaissance thinker, the Homo Universalis with a broad range of intellectual interests and expertise. Bester once placed his idealization of figures such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo into context by relating a series of incidents that occurred in his youth, some of which involved—much to his parents’ dismay—the conversion of household objects into raw materials for projects. When a piece of linoleum flooring came loose, he turned it into moveable type and quietly allowed its disappearance to be blamed on the housecleaner. He destroyed his family's Victor phonograph by using it as a potter's wheel and, in an effort to start up the Bester Barometer Corporation, fashioned weatherglasses out of water-filled light bulbs. He ruined yards and yards of wrapping paper composing symphonies with a hole-punch, wrote a verse history of the Spanish Armada that his sixth-grade teacher scoffed at because of his messy handwriting, and made a plaster-of-Paris life mask of a friend, who did not undergo the process without real danger of suffocation. Almost needless to say, his veneration for Renaissance thinkers also led him to more conventional pursuits such as chess and microscopy, and in 1925, soon after witnessing an eclipse from the rooftop of his New York City apartment building, he developed what became a lifelong fascination with astronomy and telescopic instrumentation. Bester was, in his own words, a “Renaissance kid.”4 It is not surprising that when Gernsback's Amazing Stories came along, with its emphasis on popularizing science, invention, and new ideas in general, Bester found in it a lively counterpart to his varied interests—or that he came to view SF as a Renaissance genre, as a medium especially suited to mixing and marrying various influences and branches of knowledge.

Bester's preoccupation with the Renaissance thinker inflected not only his view of SF but also his early intellectual trajectory in general. He was raised in a middle-class Jewish family with a lax attitude toward religion. His father James had grown up in Chicago, a city that Bester described as having “no time for the God bit,” and his mother Isabelle was a convert to Christian Science. In light of their own unorthodox views, his parents gave him the option of choosing his own faith. Not without an early hint of contrarian humor, he settled on a common precept of Renaissance thought: Natural Law.5 As a pre-med student majoring in zoology at the University of Pennsylvania, Bester ran up against what he remembered as the “grim specialist days of the early thirties,” but for his own part, he bucked the norm of specialization. He elected as many classes as possible in art, music, and psychology and recalled hurrying from science labs to his other classes, feeling self-conscious about the lingering scent of formaldehyde and sulfur-dioxide on his clothes.6 Outside of the classroom, he ran himself ragged with extracurricular activities. He served as moderator of the campus Philomathean Society and president of the cartooning club; joined the German, economics, and drama clubs; and chased after varsity letters, rowing on crew and playing football but distinguishing himself in particular at fencing, a fact of perhaps more than passing significance given that he named his most famous character “Foyle.”7 On top of all these other undertakings, he “went mad” in the library, reading anything and everything from Persian poet Ferdowsi's verse epic Shahnameh (ca. 1010) to French novelist Anatole France's satirical fantasy Penguin Island (1908).8 Looking back on this period, Bester admitted not only to spreading himself too thin but also to graduating from Penn in 1935 without high-enough test scores to attend medical school. (Apparently, he did not suffer this fate alone. His senior yearbook noted that on December 7, 1934, the “Pre-Med Seniors took their examination,” and as a result, there would soon “be a bunch of lawyers.”9) As it turned out, Bester did go on to study law, entering the program at Columbia University in the fall of 1936 and transferring to New York University the following year, but despite the rigors of law school, which he enjoyed, he ultimately decided that law did not suit him. In his own words, he was “just stalling” because he did not know what he wanted to do with his life.10 When all was said and done, Bester's college experience had fostered an intellectual versatility that would later serve him well as a writer, but it left him somewhat at a loose end, working in advertising.

Bester's attitude toward SF changed in important ways during college. He had continued to read the genre regularly but felt that the magazines’ horizons were shrinking at the same time that his own were expanding. His Renaissance ideal, in other words, became a kind of measuring stick for SF. Bester understood the emergence of Buck Rogers–style space opera in the late twenties and knockoffs of it such as Anthony Gilmore's Hawk Carse series in the early thirties as unfortunate signs of the field's “dissolution into pulp.”11 Fiction of this type often featured clean-cut heroes who were bare-knuckled champions of humanity and so indistinguishable from one another that Bester derisively lumped them all together under the alias “Brick Malloy,” an amalgam of the names of William Ritt's comic-strip space adventurer Brick Bradford and Lester Dent's crime-solving Chance Malloy. As Bester remembered it, some fare of this sort merely borrowed formulas from pulp Westerns, translating cattle ranches into alien planets and rustlers into space pirates. The very worst of it oozed with paranoia or racism that left him cold. To his way of thinking, it was this broader watering down of the genre, even more so than Gernsback's questionable emphasis on SF as popular science, that gave birth to the SF ghetto. He did still observe high points in the field—he cited Stanley G. Weinbaum's “A Martian Odyssey” (1934) as one of them—and he also enjoyed the grand-scale “blood and thunder” of E. E. “Doc” Smith's Skylark and Lensman series despite feeling guilty about reading them.12 However, his most important reading experiences occurred outside the pages of the SF magazines. He would later note offbeat speculations such as Olaf Stapledon's Last and First Men and Odd John, and the fiction of fin de siècle and modernist writers such as J. K. Huysmans and James Joyce as his major influences during this period.

After school, as Bester put it, he “drifted into writing.” He tried his hand at SF because he liked reading it, knew its idiom, and mistakenly believed it would be “easy to write.”13 In 1938, while still working at a publicity office, the twenty-five-year-old Bester submitted an unsolicited manuscript titled “Diaz-X” to Standard Magazines. It ended up in the hands of Mort Weisinger and Jack Schiff, two editors at Thrilling Wonder Stories, and when the three of them met to discuss Bester's manuscript, they hit it off because of their shared interest in Joyce's Ulysses, which the idealistic Bester had recently read and would “preach…enthusiastically without provocation, to their great amusement.”14 A couple of years earlier, Standard Magazines had bought the unprofitable Wonder Stories from Hugo Gernsback, adding it to its existing line of “Thrilling” titles aimed at the juvenile market, and according to legendary literary agent and comics editor Julius Schwartz, Weisinger not only liked Bester's story, he envisioned it as the basis for a promotion that could both boost the magazine's circulation and launch the young writer's career. His plan was to partner with the Science Fiction League, whose list of executive directors included Forrest J. Ackerman, Edmond Hamilton, and Ray Cummings, among others, to run an amateur story contest with a prize of $50. According to Schwartz, Weisinger later confided to him that he had set Bester's “story aside for a while, announced the contest, and then pretended to rediscover the story as a contest entry” before declaring Bester the winner.15 However, Bester's memory of the details differed from Schwartz's. He indicated that even though the contest was in the works before he submitted his manuscript, he did not intend “Diaz-X” as an entry. Having received no suitable submissions, Weisinger and Schiff approached him, told him his story “might fill the bill if it was whipped into shape,” and helped him revise it.16 Whatever the actual course of events leading up to its publication, the story became Bester's first in print. After being retitled “The Broken Axiom,” it appeared in the April 1939 issue of Thrilling Wonder alongside stories by notables such as Clifford D. Simak and Henry Kuttner. The “Meet the Author” boxout announcing Bester as the contest winner left little doubt about his continuing pursuit of the Renaissance ideal. The editors listed Bester's hobbies as “telescope making, painting, photography, playwriting, composing, and interpreting James Joyce” and revealed that when they had asked him which of the arts he would pursue given a free choice, he had replied, “all seven—or however many there are.”17

An additional circumstance surrounding Bester's first publication makes for an interesting side note. Years later, Bester interviewed Robert A. Heinlein, who revealed that a notice for the Thrilling Wonder contest had inspired him to write his very first story, “Life-Line” (1939). After Heinlein learned that he stood to make more money publishing his seven-thousand-word story in Astounding, which paid one cent a word, he submitted it there—and earned an extra $20 when John W. Campbell accepted it. At hearing this news, Bester shot back in mock anger, “You son of a bitch…I won that Thrilling Wonder contest and you beat me by $20!”18 It is interesting to consider what might have happened had Heinlein entered the contest. Bester's story, which is about a physics professor who slips into a liminal space between realities during a failed attempt to test a matter transmitter, definitely lived up to the standards of Thrilling Wonder. It even pointed toward Bester's penchant for breathless suspense and psychological realism, given that it included a long interlude of altered perception. Schwartz has suggested that Bester's story, in addition to its own merits, already had the “fix” and Heinlein's “probably would have been automatically rejected.”19 However, Heinlein was somewhat older than Bester, and perhaps for that reason, “Life-Line” showed a greater maturity of theme, examining the social and economic ramifications of the invention of a machine for predicting life expectancy. Heinlein's story holds up much better today than “The Broken Axiom,” and he may well have taken the prize even if Bester had an inside track. Another possibility is even more mind-boggling: that Weisinger might have declared Bester and Heinlein co-winners and discovered two of the most important SF authors of the twentieth century simultaneously.

Weisinger would publish three more of Bester's stories within the next year or so. The first of these, a short short titled “No Help Wanted,” fit on a single page of the December 1939 Thrilling Wonder but, regardless of its brevity, saw Bester rummaging around the writer's toolbox, exploring the use of point of view in particular. The story begins with a common-enough Depression-era scenario—a displaced, unemployed man is searching for work—but it hinges on a quick reversal of the reader's expectations, revealing the narrator to be quite different from an ordinary, down-on-his-luck drifter. He is an observer from Mars grappling with the difficulties of life on a “planet of savages.”20 The second story, “Guinea Pig, Ph.D.,” appeared in the March 1940 issue of Thrilling's new companion magazine Startling Stories and resembled “The Broken Axiom” in an important way. It turned an episode of psychological disorientation into the basis for an interval of purple prose laden with swimming sounds and colors, high-pitched emotion, and exaggerated irony. In a nutshell, a biology lecturer is snatched up into another reality, where he learns he is a mere lab rat for a higher being. Both of these efforts, like “The Broken Axiom,” employed universities as settings, suggesting that in his early days as a writer, Bester drew on his recent experiences as a student in conjuring up backgrounds and dialogue.

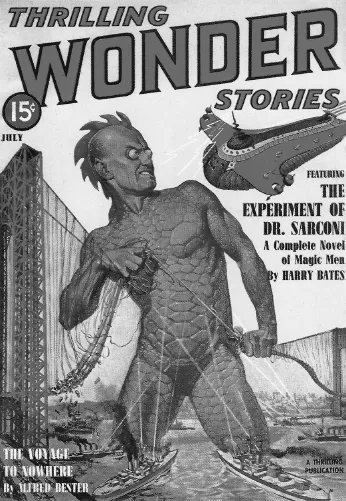

By contrast, the third story, “Voyage to Nowhere,” represented a real breakthrough on at least two levels. For one, the novelette earned Bester a small byline on the cover of the July 1940 issue of Thrilling, and in the magazine's regular “Story Behind the Story” column, the editors announced that with their encouragement, Bester had gone on from winning the magazine's first amateur story contest to become a full-fledged staff writer. Though he rarely even saved his manuscripts, much less memorabilia related to his writing, Bester kept the cover of this issue (and a few others stamped with early credits) until late in life, as nostalgic reminders of having made the transition from amateur to professional writer.21 The other step forward occurred at the level of craft. “Voyage” represented Bester's first foray into pastiche, a writing practice central to his approach throughout his career. Pastiche, of course, encompasses a range of practices—from relatively straightforward imitation of another work to truly transformative borrowing of techniques and motifs. In this instance, Bester leaned in the direction of imitation. As he pointed out in his author's comment, his story paid homage to Irvin S. Cobb's “Faith, Hope, and Charity.” Cobb was a regionalist writer who sometimes dabbled in horror, and in his story, three international criminals meet with grisly but poetic forms of justice. As they are transported by train through a barren stretch of New Mexico, on their way to deportation, they escape only to fall prey to strange accidents that resemble the forms of capital punishment awaiting them abroad in France, Spain, and Italy. By and large, Bester merely transposed this plot into space and followed Cobb in interlacing fast-paced action with slower, accruing bits of character study meant to suffuse each criminal's comeuppance with a sense of irony. Be that as it may, Bester also elaborately fleshed out the plot with science-fictional color and content, for instance, using the prison break and ensuing chase sequence to bring into play various gadgets, space hazards, and alien landscapes, and treating the disparate origins of the fugitives as a vehicle for close description of Mercurian, Venusian, and Martian physiologies and customs. In other words, even though “Voyage” bordered on a practice that Bester later came to deplore—simple translation of existing genre plots into the SF idiom—it also showed sparks of Bester's growing talent for generous invention and the adept synthesis of SF tropes.

Bester's cover credit for “The Voyage to Nowhere,” Thrilling Wonder Stories, July 1940. © Better Publications/Standard Magazines/CBS Publications.

Between the sale and publication of “Voyage to Nowhere,” Bester reached yet another professional milestone with Weisinger's help: securing an agent. Weisinger and Schwartz had co-founded a literary agency called the Solar Sales Service before Weisinger became an editor, and the two remained on friendly terms. Schwartz now represe...