![]()

1

The Politics and Production of Interiority in the Messenger Magazine (1922–23)

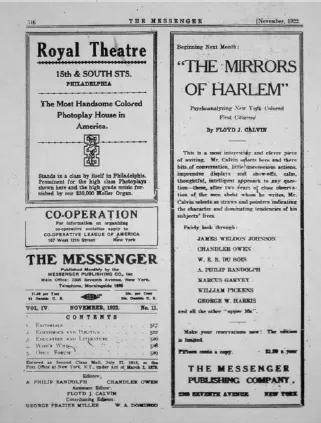

The November 1922 issue of the Messenger magazine promoted its editorial series, “The Mirrors of Harlem: Psychoanalyzing New York’s Colored First Citizens” (after the first column, the subtitle was changed to “Studies in ‘Colored’ Psychoanalysis”), which was to make its first run in the periodical in the following month. The series, written by the Messenger’s assistant editor Floyd J. Calvin, promised in-depth exposés of figures such as James Weldon Johnson, Chandler Owen, and W. E. B Du Bois. The series was advertised as “a most interesting and clever piece of writing” and validated Calvin’s lay psychoanalysis by informing the Messenger’s audience that Calvin had chosen “here and there bits of conversation, little unconscious actions, impressive displays and show-offs, calm, thoughtful, intelligent approach[es] to any question … after two years of close observation of the men about whom he writes” (516; see also fig. 1). Calvin’s psychoanalytic essays are noteworthy because they created a new standard for the periodical’s editorials and pushed the boundaries of black journalism from mere reportage to an expansive interpretation of the subject. Despite the short run of Calvin’s editorials, subsequent contributors to the Messenger followed his model by appropriating and reformulating psychoanalytic logic and vocabulary to give further credence to their political claims. Calvin’s example is significant in that he radicalized the nature of the editorial through his appropriation of a psychoanalytic model. In doing so, he provided a glimpse not only of the inner lives of his “analysands” but also of the dynamics and dynamism of African American print culture in the 1920s.

Figure 1. Advertisement for Floyd J. Calvin’s series, “The Mirrors of Harlem: Psychoanalyzing New York’s Colored First Citizens.” (Messenger, November 1922)

This chapter examines how African American print culture embraced psychoanalytic models to both revise the racist eugenicist narratives of the period and further the project of “racial amalgamation” (Hutchinson, “Mediating ‘Race’” 532) Specifically, I am intrigued by the ways in which the 1922–23 series of articles in the Messenger used psychoanalysis to engage the problem of interracialism. George Hutchinson has deftly observed that “one gleans from The Messenger the notion that cultural similarities between black and white Americans are hidden by a shared racial discourse, a culturally specific ‘American’ (that is, U.S.) phenomenon sustaining the widely shared faith in essential racial differences. Moreover, at the heart of the rituals of this faith one finds an ironic deconstruction of it, a flirting with the color line that hides while enacting the ‘amalgamation’ continually going on beneath the cover of racial reasoning” (532). Hutchinson’s interpretation of the Messenger’s program of racial amalgamation is structured largely by his reading of the socialist imperatives of the magazine, which Messenger founder A. Philip Randolph advocated primarily to promote the integration of U.S. labor unions. But in addition to the Messenger’s socialist leanings, its appropriation and revision of Freudian and Freudian-derived psychoanalysis is equally compelling in framing its mission to ally whites and African Americans. Rather than look broadly at the magazine’s various engagements with psychoanalysis, I take Robert Bagnall’s essays, “A Psychoanalysis of Ku Kluxism” and “The Madness of Marcus Garvey”; William Pickens’s “Color and Camouflage: A Psychoanalysis”; and Floyd Calvin’s short-lived editorial series, “The Mirrors of Harlem: Studies in Colored Psychoanalysis” as exemplars of the ways in which some contributors to the periodical employed psychoanalytic paradigms to ameliorate the difficult relationship between the races. I draw upon the Messenger because its staff and contributors were important arbiters of the Harlem Renaissance era, and its peak circulation of 26,000 monthly, for which two-thirds of the subscribers were African American, indicates that the information and ideas within the magazine were disbursed throughout a literate black populace (Kornweibel 52). The narrative that the Messenger’s articles present is that psychoanalytic inquiry functions as a force to radicalize thinking along racial lines because it encourages the individual to free himself from repression, which, in the essays I discuss, emerges as the barrier that disallows intimacy or even understanding between blacks and whites. The Messenger contributors I examine in this chapter all assume that more attentiveness to individual psyches can and will yield greater racial tolerance and the eventual obliteration of racial and racist thinking altogether. Though the Messenger has been expertly analyzed in terms of its sociopolitical relevance, scholars have yet to contemplate the purpose of its psychoanalytic engagements, especially as part of a larger stratagem to debunk the concept and consequences of race.1

While the Messenger’s psychoanalytic essays constituted a relatively small component of the magazine’s overall content, they nonetheless represent a significant yet overlooked element of African American intellectual history and the history of the United States. A concentrated engagement with psychoanalytic discourses within African American artistic and intellectual communities surfaced during the Renaissance era, roughly between 1916 and 1930, in the form of print media, informal salons, and literary texts. While the presence of Freudian analyses within African American artistic, cultural, and social productions in the early twentieth century has been well documented, the extent to which psychoanalysis was used as evidentiary knowledge meant to complement existing and multivalent projects of racial uplift and inclusion has not. The significance of the Messenger’s various treatments of psychoanalysis lies in their potential to disrupt existing historical narratives that, due to their relative exclusion of African Americans, suggest that black intellectual and literary communities were impervious to the pervasive psychoanalytic culture of the 1920s. Perhaps most importantly, the Messenger’s brand of “colored psychoanalysis” produced a reconciliation of psychoanalytic and socialist ideologies—a project that was considered nearly inconceivable in public mainstream discourses of the period, which sometimes highlighted competing tensions between Freudian and Marxist thought. As such, the extent of black engagement with psychoanalysis was both dialogic and revisionist in nature.

This chapter demonstrates that African American intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance era were as anxious about the liberating possibilities of psychoanalysis as their white modernist counterparts, who believed that “the negative and positive advantages of psychoanalysis appealed to the postwar generation: it gave them an apparently justifiable means of ‘scoffing scientifically and wisely’ at the old standards, and it furnished an opportunity to search for new bases of human conduct” (Hoffman 59). As such, the Renaissance era produced a body of intellectual work that deployed psychoanalysis to explode the boundaries of racial categories. That psychoanalysis would be the methodology of choice to advance an agenda that sought to deconstruct the category of race makes sense, given that psychoanalytic discourses were motivated by their privileging of an inward consciousness. For a community of people who were bound by the politics of the exterior, psychoanalysis served the desire of many African American writers and scholars who sought to promote the psychological depth of the black subject. Much has been made of the racist praxis of psychoanalysis and its contribution to nineteenth- and twentieth-century discourses of primitivity, but less attention has been given to the variant ways in which black subjects used psychoanalysis as a counterdiscursive method to assert a psychologically superior subjectivity. By marshaling the language of psychic depth, the Messenger ultimately sought to influence the political and social discourses of interracialism.2

Signifyin’ Psychoanalysis and the Rhetoric

of Interracialism

African American print culture in the 1920s and 1930s, including periodicals, newspapers, and literary texts, was instrumental in constructing and conveying a collective resistance to white hegemony. This period witnessed the emergence of major news journals, most notably the Crisis (1910), the Messenger (1917), Opportunity (1923), and the short-lived Fire!! (1926), that provided an African American populace with accounts of racial terrorism, vignettes of black achievement, artistic reviews and notices, new works of poetry and short fiction, and significant international reports on race. The Messenger, the conception of socialist and activist A. Philip Randolph, was first and foremost a socialist enterprise. In the magazine’s first issue, Randolph wrote that the mission of the publication was “to appeal to reason, to lift our pens above the cringing demagogy of the time, and above the cheap peanut politics of the old reactionary Negro leaders. Patriotism has no appeal to us; justice has. Party has no weight with us; principle has.” The first issue of the Messenger appeared in the midst of the rising popularity of the periodical. Black folks in the North as well as in the rural South consumed the pages of such publications for news and lifestyle reports that spoke to their political and social concerns. Though the magazine was often on the verge of folding, it maintained an expansive and loyal readership during its seventeen-year existence.

The Messenger’s credo distinguishes it from the two other popular periodicals of the time—the NAACP’s Crisis and the Urban League’s Opportunity— which were more artistically focused and coincided with the Du Boisian and Lockian beliefs that racial progress could be accomplished through artistic achievement. Sondra K. Wilson has noted that “The Messenger called for a brand of socialism that would emancipate the workers of America and institute a just economic system. Randolph and [Chandler] Owen believed that centuries of capitalism had perpetuated the existing system which disenfranchised both black and white workers, and they conceived the idea of using unions as a means to achieving a smooth and painless socialist revolution” (xxii). Randolph and Owen also assumed that by marking the similarities between the black and white working class, other social and cultural bridges could be formed between the races. Hutchinson remarks that “The Messenger attributed racial prejudice to capitalism, insisted on the ‘Americanness’ of African Americans, and continually called for interracial worker solidarity … if the United States was to be the site of a new form of ‘indigenous’ socialism, it also, The Messenger suggested, would give birth to a new people and a ‘mulatto’ national culture” (Harlem Renaissance 291). The Messenger frequently published cartoons that depicted the parallel social and economic plights of the black and white working classes in order to emphasize the message that there was very little, if any, distinction between the races and that the root cause of racism was U.S. capitalism, which threatened everyone. One illustration depicts a black dog and a white dog chewing on the same bare bone while the abundant fat meat of financial profits are available to the “capital” hound. The image not only is a stark representation of the magazine’s socialist impetus, but it also gives a sense of the Messenger’s call for interracial solidarity.

The Messenger’s emphasis on interracial solidarity for workers remained a consistent theme even when A. Philip Randolph temporarily left to pursue his work with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1923 and George Schuyler took rein of the magazine. However, the trope of interracialism broadened into a more cultural and intimate context under Schuyler. Even before Schuyler’s arrival, the Messenger’s ideological focus was more interracial than intraracial, but after Schuyler became editor the magazine began to emphasize its goal of a mulatto nation. Schuyler undoubtedly had a personal investment in establishing and promoting the interracialist cause: his wife, Josephine Cogdell, was white, and he believed his daughter to be representative of the “potential rise of a new or superior American racial type, a mulatto master race of democrats” (J. Ferguson 18). Thus, the currency he afforded to the project of interracialism during his tenure was considerable.

The irony of the Messenger’s attempts at an African Americanist psychoanalytic inquiry, specifically in pursuit of a mulatto nation, is that it reinscribes the very notion of race mixing or Mischling that Freud desperately and consciously elided in his own analysis. Freud was famously ambivalent about his origins as an Eastern Jew. Bearing witness to the subjugation of Eastern Jews, Freud constructed his own self-image as an acculturated Jew. The increasingly anti-Semitic environment of Central Europe, which was perpetuated by the medical sciences, led to the spawning of creative racial narratives meant to further demonize Jews by aligning them with an even more reviled race, the African. Such began the fiction that, as Sander Gilman notes, “Jews are a ‘mongrel’ race, who interbred with Africans during the period of the Alexandrian exile.” This fiction led to the construction of “the fantasy of the difference of the male genitalia was displaced upward—onto visible parts of the body, onto the face and the hands where it marked the skin with blackness” (Freud 21). At its inception, Freudian analysis was overdetermined by an insistent claim of Jewish purity to dissociate it (and Freud himself) from the primitive African. Yet even in its glaring absence from psychoanalytic discourse, blackness figures as a defining category that essentially determined Freud’s formation of the white or off-white Jewish subject. According to Gilman, Freud’s anxieties about racial purity were heightened in 1911, when he became a member of the International Society for the Protection of Mothers and Sexual Reform, which advised its members to breed selectively. However, Freud’s continuous clashes with anti-Semitism marked by his racially infused rift with Carl Jung led him to declare a Jewish nationalism that was distinct from any other racial category, including Aryan. To invoke Freudian and Freudian-derived psychoanalysis to bring together the distinct racial categories that Freud believed eternally dissimilar was a radical reimagining of the uses of psychoanalytic thought. For Freud, blackness signified a space of willful ignorance or unknowability, but for the writers of the Messenger, blackness structured the entire framework of the white psyche and the social conditions that those psychical inclinations produced.3

The Privileging of “Depth”: Floyd Calvin’s Psychoanalytic Subjects

The Messenger’s first and most explicit engagement with the psychoanalytic culture of the 1920s emerged in Calvin’s “Mirrors of Harlem” essays, the first of which coincided with the beginning of George Schuyler’s tenure at the Messenger.4 The series signals one of the many substantive and stylistic transformations the magazine was to experience under Schuyler’s direction, specifically a greater investment in American popular culture and hence the magazine’s interest in psychoanalytic thought. Calvin’s column was less concerned with the science behind psychoanalysis and more interested in the liberty it allowed for an uncensored critique of his political and social adversaries. Although Calvin’s employment of psychoanalysis was not explicitly an effort to further an interracial ideal, it is appropriate and significant to underscore Calvin’s column because it provides substantive clues about the role that psychoanalysis played within black intellectual and cultural spheres that were decidedly dissimilar from white American appropriations of the science. In particular, this section examines the ways in which Calvin’s deployment of psychoanalysis was an attempt to distinguish the Messenger from other popular magazines of the period, such as the Crisis (edited by W. E. B Du Bois), Opportunity (edited by Charles Johnson), and the Negro World (edited by Marcus Garvey). But Calvin sought to accomplish more than simply point to the ways that the Messenger was different from these other publications; he also wanted to discredit other writers by performing disparaging psychoanalytic readings emphasizing, in particular, their lack of depth.

During this period, there was a great deal of competitive jockeying for legitimacy and authority in black magazines. As such, the editorial was arguably the most important feature of the Messenger, as it was central to the establishment of the publication as the only ideologically and politically accurate news source for the black populace. At this time, a periodical’s editors could dramatically impact the success or failure of the publication. This was certainly the example of the Crisis, which witnessed a growth in circulation from 1,000 in 1910 to 94,000 in 1919, paralleling the rise of Du Bois’s popularity and influence in intellectual an...