eBook - ePub

Johanna Beyer

About this book

Composer Johanna Beyer's fascinating body of music and enigmatic life story constitute an important chapter in American music history. As a hard-working German émigré piano teacher and accompanist living in and around New York City during the New Deal era, she composed plentiful music for piano, percussion ensemble, chamber groups, choir, band, and orchestra. A one-time student of Ruth Crawford, Charles Seeger, and Henry Cowell, Beyer was an ultramodernist, and an active member of a community that included now-better-known composers and musicians. Only one of her works was published and only one recorded during her lifetime. But contemporary musicians who play Beyer's compositions are intrigued by her originality.

Amy C. Beal chronicles Beyer's life from her early participation in New York's contemporary music scene through her performances at the Federal Music Project's Composers' Forum-Laboratory concerts to her unfortunate early death in 1944. This book is a portrait of a passionate and creative woman underestimated by her music community even as she tirelessly applied her gifts with compositional rigor.

The first book-length study of the composer's life and music, Johanna Beyer reclaims a uniquely innovative artist and body of work for a new generation.

Amy C. Beal chronicles Beyer's life from her early participation in New York's contemporary music scene through her performances at the Federal Music Project's Composers' Forum-Laboratory concerts to her unfortunate early death in 1944. This book is a portrait of a passionate and creative woman underestimated by her music community even as she tirelessly applied her gifts with compositional rigor.

The first book-length study of the composer's life and music, Johanna Beyer reclaims a uniquely innovative artist and body of work for a new generation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

eBook ISBN

9780252097133Subtopic

Music Biographies1 Sunnyside, 1927–1933

Aside from official paperwork—birth and death certificates, residency registrations, ship manifests, passport numbers—the earliest currently knowable fact of Beyer’s biography occurred in 1927, when she was thirty-eight years old. Therefore, our survey of Beyer’s life begins on October 30, 1927, when the Smith College social worker Bertha Reynolds first recorded Beyer’s existence in her diary. Now working at the Institute for Child Guidance and the Jewish Board of Guardians in New York, Reynolds sought a place to live outside the metropolis: “I had dreaded New York City as a home, feeling it would offer only the rock-bound canyons of a metropolis or exhausting commuting at the end of each day,” Reynolds wrote later in her published memoir.1 On a Saturday afternoon, she went to a new development in Queens called Sunnyside Gardens, at the suggestion of a co-worker. This housing project, begun in 1924, was still being built, and it featured two-story brick houses surrounding neighborhood green spaces meant for communal use. The housing development management office sent Reynolds to “a German music teacher, Miss Johanna Beyer,” who had purchased one of the new homes and wanted to rent one of her rooms. Reynolds eloquently recorded this day, and the bucolic atmosphere in Beyer’s neighborhood, in an “informal autobiography”:

I liked Miss B., engaged her east bedroom, and so started a friendship of 17 years, which ended with her death by multiple sclerosis. I shall never forget the satisfaction I felt in living close to the warm brown earth, hearing the rain fall on leaves, and seeing it soak into the ground in the garden under my window. I had been starved for the earth in city blocks and said that never again would I live that way. In twenty years I lived in Sunnyside I never lost my love for the green gardens and the whispering trees that grew there.2

In her published memoir, Reynolds wrote further of Sunnyside and Beyer: “I loved that Sunnyside community for all the twenty years it was my home, and my friendship with Miss Beyer lasted as long as she lived.”3

Beyer’s new house, in the southwest edge of the development near the crossing with Skillman Avenue, appears to have been registered as a new building with the New York City Department of Buildings in 1926. It is most likely that she became the first owner of this two-story structure in the section of Sunnyside called Madison Court in the summer of 1927; her name first appeared in the Queens directory in the winter of 1927–28.4 The 1930 census lists the value of her home as $11,700.5 The area was considered a special district for working-class housing, a planned seventy-seven-acre, garden-dominated community lined with sycamore trees, now managed as a National Register Historic District. By the mid-1920s the rapid transit system allowed residents to travel into the Forty-Second Street station in Manhattan in a mere fifteen minutes.

Clarence S. Stein, town planner and chief architect of Sunnyside Gardens, described the community feeling of activism in the housing project:

There was one important difference between the people of Sunnyside and the others. Sunnyside was a community of people accustomed to meeting and doing things together—a real neighborhood community. The others were lone individuals with no organized social or other relations with the people who lived next door. At Sunnyside a home-owners’ group was quickly formed; it comprised a majority of the community. The home-owners, as a community group, were soon ready to ask, and if necessary to fight, for a postponement of or a decrease in mortgage payments. In the end they went on strike and, as a group, refused to make payments.6

Sunnyside Gardens was the center of Beyer’s social life.7 Reynolds lived with Beyer for several years, and they were active with a circle of women friends and a number of Beyer’s nieces. After a few years Reynolds moved to a different house in Sunnyside Gardens, a few blocks away from Beyer, at 3947 Forty-Eighth Street. The two properties were centers of activity for these women, and Beyer continued to spend time at Reynolds’s house even after she moved to Manhattan in 1936. Friends in Beyer’s community during this time included not just Reynolds and Beyer’s niece Frida, who lived with Beyer for some period around 1930, but also the influential piano teacher Abby Whiteside, and Reynolds’s cousin Erdix Winslow Capen (1909–1995), who was also a frequent visitor to the community.8 After Reynolds moved out, Beyer rented briefly to Willard Espy (1910–1999), a writer for World Tomorrow who would go on to publish some twenty books, many of which were about wordplay, a practice in which Beyer apparently delighted. A later tenant of Beyer’s named Elizabeth Rice was quickly integrated into Beyer’s and Reynolds’s circle of friends.

Reynolds’s diary records details of Beyer’s activities and dramatic events during the late 1920s. Shortly after Reynolds moved in, in November 1927, three of Beyer’s nieces also occupied the household. A few months later, in March 1928, one of the nieces had a psychotic breakdown and disappeared; police found her days later and checked her into Kings Park Psychiatric Center in Brooklyn, where she died of heart failure within the week. In May 1928, another niece, Gertrude, visited and then married; a reception was held at Beyer’s house (Gertrude and her husband would be among the few attendees at Beyer’s memorial service in 1944). That summer, Reynolds paid Beyer twenty dollars to keep her room during her holiday travels; in July, Beyer and Frida took a vacation to Washington, D.C., where they were photographed in front of the Library of Congress.

Beyer’s friendship with Reynolds seems to have brought her into a world of political activism and engagement with social and racial issues of the late 1920s and early 1930s. But Beyer had forged important friendships of her own before meeting Reynolds. In January 1928, Beyer met up with Reynolds at the International House (Morningside Heights), where Beyer introduced Reynolds to her friend, a young Trinidadian man named Francis Eugene Corbie (1891–1928), with whom the women then attended an art exhibit. It is presently unknown how Beyer first met Corbie, who was a well-known activist in public affairs and a prominent political speaker. City College’s Campus News called him “the foremost undergraduate Negro student in America.”9 (Corbie also seems to have acted in a melodramatic comedy called Cape Smoke; or, The Witch Doctor, which ran at the Martin Beck Theatre in 1925.)10 During the summer of 1928 Corbie became ill and returned to his family home in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, where he died on October 3.11 On a Sunday evening in November, Beyer and Reynolds attended Corbie’s memorial service, held at the Community Church of New York and led by Rev. John Haynes Holmes, a pacifist known for his antiwar activism, and a cofounder of both the ACLU and the NAACP. A few years later Beyer would attend the NAACP annual meeting at St. Mark the Evangelist Church in Harlem.

Beyer’s political engagement during this period embraced both national and international developments, and she and Reynolds were active in the Town Hall Club, an important cultural and political center in Manhattan. In November 1928 Beyer and Reynolds attended a meeting about Franklin Roosevelt’s New York gubernatorial campaign, and on New Year’s Day 1929 Beyer gave a dinner party for a Mr. Arthur Moore and a woman involved in the Roosevelt campaign. Beyer also read avidly, keeping up on German politics with the help of the February 1929 issue of Survey Graphic, an issue devoted to “The New Germany 1919–1929,” and she and Reynolds discussed the advantages of Germany’s multiparty political system.12 The women often spent time at a local coffeehouse and frequented several ethnic (Japanese, Indian) restaurants, no doubt eagerly discussing both local and global current events.

In January 1930 Beyer was naturalized as an American citizen; in July, with a new American passport in hand, she traveled to Germany for a two-month visit. On her 1930 passport application, she requested that her passport be mailed to an organization called Open Road Inc., which arranged for students and professional people to travel to Europe for the purposes of studying labor and socialist practices overseas, including in Soviet Russia. There is no indication that Beyer participated in one of these tours, but she may well have known the organizers of Open Road. This connection to a socialist-friendly group during this period of her life is not surprising, given all the evidence that places Beyer in the middle of a community of political activists sympathetic not only to socialist ideals and labor issues but also to racial and civil rights struggles.

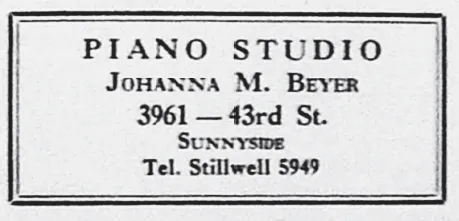

On her 1930 passport application, Beyer listed her occupation as “music teacher.” But Beyer’s work during this period included both private piano teaching and professional accompanying in concerts, as well as work in dance studios.13 For a time Beyer worked as an accompanist at the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts, where Doris Humphrey taught dance until 1928. And as a conservatory-trained pianist, Beyer had the credentials to draw in paying piano students. She ran an advertisement for her piano studio in the November 1929 issue of the local Sunnyside News.

Beyer had at least one close competitor, a Sunnyside neighbor one block over named Helen Gollomb Tuvim (mother to actress Judy Holliday), who placed a similar ad in the September 1930 issue of Sunnyside News; Tuvim’s “modern, progressive, psychological method” of piano teaching was going for a “special offer of $1.00 a lesson.”14 It is safe to assume that Beyer charged something similar.15 Beyer also gave piano lessons to Reynolds, although it is unclear if money exchanged hands; together they studied, among other works, Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony.

Amid all this social, political, and professional activity, Beyer’s compositional imagination began to flourish, and it was in February 1931 that she composed and dated her earliest known work, a waltz for piano (now part of the Cluster Suite). Beyer’s 1937 curriculum vitae also lists performances of original compositions from around this time, including a March 1931 performance of works Beyer composed for a dancer named Mara Mara at “An Exhibition of Persian Art and its Reaction on the Modern World,” which opened with a special reception at the Brooklyn Museum. Her 1937 CV also lists among her accomplishments original music composed for dances at the innovative and experimental Dorsha Hayes Theater of the Dance. The worlds of socializing, politics, and culture were closely intermingled in the interwar years: on Memorial Day 1932, after hosting a birthday party for one of her friends, Beyer and her guests attended a Socialist Party meeting at P.S. 125 during which Dorsha and Paul Hayes entertained.

Advertisement for Beyer’s private piano studio, published in Sunnyside News, November 1929; copy located by Herbert Reynolds in the E. E. Wood Papers, Avery Library Drawings and Archives, Columbia University.

The spring of 1931 featured a number of musical events that may have helped lead Beyer down the path of ultramodernism and, eventually, to Henry Cowell: in February, Léon Theremin demonstrated his eponymous new instrument at the New School (Cowell would present his Rhythmicon there nearly a year later); that same month conductor Nicolas Slonimsky gave a Pan-American Association of Composers concert that included music by Cowell, Ives, Ruggles, Henry Brant, and Alejandro García Caturla; on March 31, Cowell gave a piano recital at the New School. In May 1931, the Greenwich Village Music Festival offered a program of compositions by Marion Bauer and other New York-based composers; Charles Seeger of the New School for Social Research spoke on Paul Hindemith’s utilitarian concept of Gebrauchsmusik at the Greenwich House Music School.

As mentioned above, our earliest direct knowledge of Beyer’s compositional work occurred in 1931; by January 1932 she was sharing her new work with her Sunnyside friends. Between February and May of that year, Reynolds documented three important facts—particularly significant for reviving Beyer’s biography because her connection to the Seegers has long been discussed as a fact without any concrete evidence:

10 February: Johanna had interview w. Charles and Ruth Seeger—teachers of modern composition. They will give her lessons.

10 March: Johanna giving German lessons to Seegers to pay for comp. lesson every week.

12 May: Johanna composing.

That summer, Beyer submitted a piece to the arts competition at the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.16 In July and August she penned two poems—“Universal-Local” and “Total Eclipse”—which she would set to her own music two years later.

By the end of 1932 Beyer was having significant financial difficulties, and she hired workmen to refurbish her basement so she could live there while renting out the rest of her house; she had lost another tenant and was worried about her debts. Perhaps to distract her from such worries, Reynolds took her to a housewarming event for a socialist organization called Pioneer Youth of America; in January 1933 the friends attended a socialist meeting in Sunnyside “on Technocracy.”

Beyer’s friendships with Eugene Corbie, Bertha Reynolds, Dorsha Hayes, Abby Whiteside, Erdix Capen; her activities as an engaged aunt to many visiting nieces; her association with pacifists, socialists, left-wing sympathizers, and black activists during the Harlem Renaissance and the Depression; and her involvement in the Sunnyside Gardens community as a pioneering homeowner, landlady, music teacher, and hostess offer a much different view of her personality and social life than we have previously received, the latter a misleading history in which professional acquaintances described her as “strange and difficult to know,” “angular, awkward, and self-conscious,” “problematic,” “extremely quiet,” and, most condescendingly, “always there to lick stamps.”17 In fact, she led a rich life filled with accomplished people, intellectual pursuits, and compositional ambition. But our perspective on Beyer shifts dramatically around 1933. In this year of massive changes—Prohibition ended, Roosevelt took office, banks closed, Adolf Hitler was elected, and on and on—Beyer’s musical and emotional world began to be dominated by her relationship with Henry Cowell and would remain so for much of the final eleven years of her life.

2 Compositional Beginnings, 1933–1936

Beyer’S compositional beginnings soon brought her into the orbit of the New School for Social Research. For the 1933–34 school year, the New School listed among its instructors Henry Cowell, Roy Harris, Hanya Holm, Doris Humphrey, Harry A. Overstreet, Paul Rosenfeld, Charles Seeger, and Roger Sessions, among others. As the first fascism-fleeing wave of European immigrants started to descend upon New York, the New School became an importa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: From Leipzig to the Bronx

- 1. Sunnyside, 1927–1933

- 2. Compositional Beginnings, 1933–1936

- 3. Having Faith, 1936–1940

- 4. New York Waltzes: Works for Piano

- 5. Horizons: Percussion Ensemble Music

- 6. The People, Yes: Songs and Choral Works

- 7. Sonatas, Suites, and String Quartets: Chamber Music

- 8. Symphonic Striving: Works for Band and Orchestra

- 9. Status Quo

- 10. Beyer’s Final Years, 1940–1944

- Conclusion: “May the Future Be Kind to All Composers”

- Appendix A Biographical Data

- Appendix B Chronological List of Beyer’s Known Works

- Appendix C Publications of Beyer’s Music

- Appendix D Selected Recordings of Beyer’s Music

- Appendix E Beyer’s Poetry

- Notes

- Sources and Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Johanna Beyer by Amy C. Beal in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.