![]()

1

Africa, Arise! Face the Rising Sun!

W. E. B. and SHIRLEY GRAHAM DU BOIS

On February 23, 1959, W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–63), accompanied by his wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, celebrated his ninety-first birthday by speaking to more than 1,000 faculty members and students at Beijing University, China’s most prestigious institution of higher learning, and to the world by radio (fig. 1.1). In his epic speech, Du Bois proclaimed Chinese and African dignity and unity in the face of Western racism, colonialism, and capitalism. He opened his speech grandly, “By courtesy of the government of the six hundred and eighty million people of the Chinese Republic, I am permitted … to speak to the people of China and Africa and through them to the world. Hail, then, and farewell, dwelling places of the yellow and Black races. Hail human kind!” Du Bois declared that the “ownership” of “my own soul” led him to dare “advise” Africa to follow China’s leadership and recognize its understanding of the color line. “China after long centuries has arisen to her feet and leapt forward. Africa, Arise, and stand straight, speak and think! Turn from the West and your slavery and humiliation for the last 500 years and face the rising sun. Behold a people, the most populous nation on this ancient earth which … aims to ‘make men holy; to make men free.’ … China is flesh of your flesh and blood of your blood.” He urged China in turn to recognize that it is “colored and knows [to] what a colored skin in this modern world subjects its owner.” Du Bois answered his own concern by noting that “China knows more, much more than this; she knows what to do about it.” He concluded the speech pleading that Africa and China “stand together in this new world and let the old world perish in its greed or be born again in new hope and promise. Listen to the Hebrew prophet of Communism: Ho! Every one that thirsteth; come ye to the waters; come, buy and eat, without money and without price!”

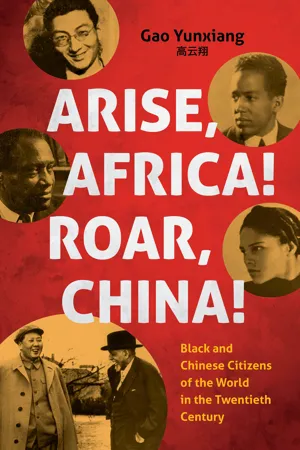

FIGURE 1.1. W. E. B. Du Bois lectures at Beijing University in a celebration of his ninety-first birthday, February 23, 1959. Courtesy of W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, mums312-i0685, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Afterward, the speech was reprinted and distributed widely. Du Bois proudly recalled how his birthday was accorded a “national celebration … as never before.” The People’s Daily, the mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, praised his speech and headlined its full coverage with the title “Du Bois Issues a Call to the African People: Africa, Arise! Face the Rising Sun! The Black Continent Could Gain the Most Friendship and Sympathy from China.” The speech was soon published in Peking Review, a popular global mouthpiece of Communist China. To accompany Du Bois’s speech, Jack Chen, an editor of the magazine and Sylvia Si-lan Chen’s brother, contributed a cartoon illustrating Uncle Sam offering a new gilded chain of dollar signs to a muscular Black man breaking his old one. Footage of the speech would be prominently featured in a documentary on the Du Boises’ visit made by the Central News and Documentary Film Studio on behalf of the Chinese People’s Association for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (Zhongguo renmin duiwai wenhua xiehui, CPACRFC).1 Outside of China, the New York Times, a less sympathetic newspaper, reported, “Dr. Du Bois summed up his bitterness at the United States by saying in his speech that ‘in my own country for nearly a century I have been nothing but a nigger.’”2

W. E. B. and Shirley Graham Du Bois’s visit was part of their triumphal world tour from August 8, 1958, to July 1, 1959, which Du Bois called “the most significant journey” of his life. It became possible after the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the U.S. State Department lacked the authority to deny passports to citizens who refused to sign the affidavit that they were not communists. The Du Boises responded by immediately applying for and securing their passports.3 The Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) both extended welcoming hands to the long-isolated couple, who eagerly added China to their itinerary.

Du Bois’s milestone trip and speech afforded the PRC a measure of political dignity and status that it badly needed in 1959. During the Great Leap Forward, the CCP’s first major crisis, and increasing Sino-Soviet tensions, Mao Zedong wished to cultivate alliances with emerging African nations and regarded Du Bois, with his immense international reputation, as key to that effort.4 Du Bois felt honored and enlightened in turn by what he saw in China. He regarded China and Africa as joined in their present and future battles against Western imperialism and capitalism. If the Chinese wanted to teach Du Bois about the need for international revolution, he was ready to applaud and support their efforts. With Communist China now replacing Japan as the beacon of hope in Asia, Du Bois’s advocacy of a joint Pan-Africanism and Pan-Asianism reached a new height.

Historically, Du Bois’s views of China and Asia had evolved within shifting political and ideological contexts. The message of his 1959 visit to China stood in sharp contrast to the statements he delivered after his little-noticed first trip to Asia in 1936. In the midst of China’s national crisis stemming from Japanese military aggression, Du Bois had proclaimed, “I believe in Japan. It is not that I sympathize with China less, but that I hate white European and American propaganda, theft, and insult more. I believe in Asia for the Asiatics and despite the hell of war and fascism of capital, I see in Japan the best agent for this end.” Finding a lack of racial strength in the Nationalist government, Du Bois then anointed imperial Japan as the pillar of Asia, a position that sparked outrage in the United States and China—and that he did remark upon twenty-three years later.5

The Du Boises’ visits to China are well known, but scholars have not accorded them much importance. Their high-profile 1959 trip has received the most notice, yet David Levering Lewis, Du Bois’s most significant biographer, dismisses it as naive, a common perception.6 Most scholarly attention has focused on the consequences of this trip in the United States. Robin D. G. Kelley, Bill V. Mullen, and other scholars have detailed its importance for understanding Du Bois’s philosophy of the unity of people of color and the trip’s impact on Black radicals of the 1960s. Mullen, the leading commentator on Du Bois’s writings on Asia, contends that this visit stoked Du Bois’s anticolonialism, a major theme in the later decades of his active life.7 Looking through the lens of China’s official coverage of the event, it becomes clear that the time that the Du Boises spent in China was mutually beneficial for the guests and their hosts. Du Bois learned much from China and from his wife’s experiences there. In turn, the Chinese benefited from their influence among Black and national communities.

Shirley Graham Du Bois played an important role in their visits to China and their aftermath. Her biographer Gerald Horne has done much to enhance Graham Du Bois’s reputation after several decades of neglect and disdain.8 Yet even Horne’s work has not fully analyzed the couple’s visits to China in 1959 and in 1962 or credited Graham Du Bois’s contributions. This chapter reveals how Graham Du Bois became a key interpreter of her husband’s vision of China. Her devotion to the cause of women there during and after the visits helped Du Bois change his views of China as weak to the new understanding of a developing nation inhabited by robust men and women. After Du Bois’s death, Graham Du Bois’s personal involvement with significant actors in the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) added new dimensions of the ties between Red China and Black America.9

W. E. B. Du Bois’s famous dictum that the question of the twentieth century is that of the color line takes on even broader meaning in the light of these visits. The Du Boises’ trips to China and comments on China and Asia within the context of race, colonialism, capitalism, and socialism or communism enlarged the story of their lives and thought. It becomes clear that Du Bois’s story of the color line in the twentieth century is incomplete without the Chinese perspective.

DU BOIS’S EARLY VIEWS: “ASIA FOR THE ASIATICS”

In his semiautobiographical Dusk of Dawn, published in 1940, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that, beyond the “badge of color,” the “social heritage of slavery” and “the discrimination and insult … binds together not simply the children of Africa, but extends through yellow Asia and into the South Seas. It is this unity that draws me to Africa.” He further articulated this sentiment in his 1958 letter to Madam Sun Yat-sen: “From my boyhood I feel near them [the Chinese]; they were my physical cousins.”10

China had played a part in Du Bois’s hopes for the unity of people of color since the publication of The Souls of Black Folk in 1903. The “martyrdom [in Africa in 1885] of the drunken Bible-reader and freebooter, Chinese Gordon,” who had helped to suppress the Taiping Rebellion, had first signaled for him white dominance in both Africa and China. Du Bois noted that white colonialism in Asia ushered in “a particular use of the word ‘white’” in the colonial vocabulary of race. White imperial powers’ attempt to divide China in the late nineteenth century marked the climax of colonialism, Du Bois announced at the 1909 National Negro Conference.11

China and Asia helped Du Bois debunk a white supremacism that sustained colonialism through pseudoscience and religion. In his 1897 essay disputing the classification of human races through comparative anatomy, Du Bois prominently noted the allegedly “yellow” skin, the “obstinately” straight hair, and the monosyllabic language of the Chinese. Citing the cultural giants of China and other Asian countries, Du Bois asserted that white “brains and physique” were not superior to those of the “Indian, Chinese or Negro.” “Run the gamut,” he demanded in 1920, “and let us have the Europeans who in sober truth overmatch Nefertiti, Mohammed, Rameses, and Askea, Confucius, Buddha.” Du Bois went on to affirm the advancement of Chinese civilization in 1931: “China is eternal. She was civilized when Englishmen wore tails. … Before Civilization was, China is.” He proposed inserting photographs of Paul Robeson, Sun Yat-sen, and President Calvin Coolidge in American geography textbooks as visual representatives of the “three great branches of humanity.”12 Du Bois predicted that the discovery that color and racial prejudices were “largely lies and assumptions” rather than science would empower the oppressed races. He asked rhetorically in 1920, “What is this new self-consciousness leading to? Inevitably and directly to distrust and hatred of whites; to demands for self-government, separation, driving out of foreigners—‘Asia for the Asiatics,’ ‘Africa for the Africans,’ and ‘Negro officers for Negro troops!’”13

By embracing China’s 1911 Revolution and World War I as vehicles for the social and economic uplift of nonwhites, Du Bois directly linked the struggles of African Americans and those of nationalist forces in China. His editorial in the Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), predicted that the establishment of the Republic of China would usher in “a world where Black, brown and white are free and equal.” Du Bois was confident that the Great War would lead to “an independent China, a self-governing India, an Egypt with representative institutions, and an Africa for Africans’ sake and not merely for business exploitation,” in addition to “an American Negro, with the right to vote and the right to work and the right to live without insult.”14 During the First Pan-African Congress in Paris, Du Bois presented a memorandum to U.S. president Woodrow Wilson at the Versailles Peace Conference, urging that the principle of self-determination be universally applied to “inaugurate on the dark continent a last great crusade for humanity. With Africa redeemed, Asia would be safe and Europe indeed triumphant.” The Chicago Tribune dismissed his “scheme” as “quite Utopian, and it has less than a Chinaman’s chance of getting anywhere in the Peace Conference, but it is nevertheless interesting.”15 Even so, Vladimir Lenin and, later, the CCP echoed Du Bois’s views.

Du Bois closely monitored events unfolding in China following the 1911 Revolution. In the Crisis, he discussed how the Northern Expedition jointly launched by the Nationalist Party and the CCP between 1926 and 1927 overcame setbacks under warlords. For Du Bois, it signaled the painful birth of a free modern China, one “slowly and relentlessly kicking Europe into the sea.” He initially refused to believe that the Northern Expedition was falling apart and condemned threats of foreign intervention, particularly by the United States. After Chiang Kai-shek’s bloody purge of the CCP, Du Bois repeatedly denounced him as a “traitor.” When Chiang, influenced by his new wife, May-ling Soong, converted to Methodism, Du Bois poured scorn on the general. “China has had enough troubles, but now that it is reported that Chiang Kai-shek has embraced Christianity. ‘We can confidently expect anything.’” Nonetheless, Du Bois remained optimistic that revolutionary forces in China would rid the land of “home grown exploiters and foreign leeches.” Soon he led the Fourth Pan-African Congress in New York City to pass a resolution demanding “real” national independence of China, India, Egypt, and Ethiopia and the rights of Africans and African-derived peoples.16

Insisting “Asia for the Asiatics” in opposition to white colonialism, Du Bois could not avoid the complex position of Japan in imperial struggles over the color line. While Japan rose as the only colonial power in Asia at the expense of China and Korea following the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), Du Bois welcomed “the sudden self-assertion of Japan” for breaking down “a whole vocabulary” of white colonialism on racial supremacy. He further applauded the maneuvers of “yellow” Japan during World War I, which defied “the cordon of this color bar” and threatened “white hegemony.”17 However, as early as 1885, the influential Japanese philosopher Yukichi Fukuzawa had explicitly advocated that Japan “leave the ranks of Asian nations and cast our lot with the civilized nations of the West.” U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt granted Japan the status of honorary Aryan to carry on the “white man’s burden” at the end of the 1905 Russo-Japanese War. Du Bois expressed concern ...