![]()

Chapter 1

Early History

Many towns in the United Kingdom have guildhalls. They are usually just called ‘The Guildhall’. London’s Guildhall is often referred to simply as ‘Guildhall’ but nobody seems to know why. It is just one of the mysteries surrounding this extraordinary building.

London was founded by the Romans. Before they arrived there was no significant settlement where London is now. Archaeologists have found some evidence of scattered pre-Roman human habitation but, as far as we know up to this point, nothing significant to speak of. Julius Caesar did not mention anything in his writings.

The founding of London was not in 55 BC when Caesar first came and famously said ‘I came, I saw, I conquered,’ but around a hundred years later in AD 43 when Emperor Claudius decided to mount a full invasion, led by general Aulus Plautius.

The Romans settled where London is now for several reasons. It was the lowest bridgeable spot on the River Thames, the site provided a good natural harbour for their ships and the river was tidal up to the London area. It would be useful as a landing place for troops to further the invasion of Britain and also for trade between the province of Britannia and Rome. The river provided a good defence should there be an attack from the south. There were also some hills to the north which could be settled and provide useful defensive positions against any attack that might come from that direction.

The Roman city of Londinium was founded roughly where the modern City of London – the Square Mile – is today. Remains of the earliest settlement, from around AD 47, were found under the building No 1 Poultry. There was a break in development in AD 60 when Boudicca, the Queen of the Iceni tribe in East Anglia, rebelled against the Romans after they betrayed her. She destroyed Camulodunum (Colchester), Verulamium (St Albans) and burned down Londinium. She and her armies were later defeated, and archaeologists call this early layer the ‘Boudiccan destruction horizon’. After her attack the city was rebuilt. There is an unproved myth that she may be buried under King’s Cross Station.

There is also a mythical story of London’s first origins, in which it was founded by Brutus of Troy. The myth starts with the Roman emperor Diocletian, who had thirty-three daughters. The eldest was called Alba. Diocletian found husbands for his daughters but, goaded on by Alba, the daughters killed the husbands. To punish them Diocletian put them on a boat with six month’s supply of food and sent them out to sea. They arrived at an island, Britain, populated by giants. They named it Albion after older sister Alba, and the sisters and the giants between them produced another race of giants.

The myth continues that Brutus of Troy landed on Albion. He was said to be a descendent of Aeneas, a hero of the Trojan Wars. After the fall of Troy, when the ancient Greeks sacked the city using their wooden horse, Aeneas journeyed to Italy. Brutus was born there, but killed his parents and was exiled. After some wanderings with his followers he came to Albion, which is now named Britain after him.

Here Brutus founded a city on the site of London named New Troy, his palace where Guildhall is now. He fought with the giants of Albion for control of Britain. There are different versions of these battles. One story is that two of the giants, Gog and Magog were defeated, taken prisoner and brought to New Troy where they acted as guardians of the palace. The myth persisted and they are represented by the statues of Gog and Magog in Guildhall’s Great Hall. Another version of the legend is that the Magog figure in the Great Hall is that of Corineus, a warrior who joined Brutus of Troy in his wanderings and helped him defeat the giants. None of the Brutus of Troy story is true. It is all legend, but it was generally thought to be the truth until the sixteenth century and by some even after that.

Gog and Magog, carved by Richard Saunders in 1709. Each stood thirteen feet tall. Destroyed in the Blitz, 29 December 1940.

Another legendary founder of London was King Lud. Ludgate is named after him.

To return to the true story of London, it was rebuilt after Boudicca’s attack and had a good complement of Roman amenities – such as a forum, baths, Governor’s house and basilica. Archaeologists have found evidence of all of these. However, one thing seemed to be missing. A Roman city the size of Londinium should have had an amphitheatre, and there was not any archaeological evidence of one. During the Second World War the Guildhall Art Gallery was bombed and after the war it was decided to build a new one. After some delay, work began and the foundations were sunk – and in 1988 they found the remains of the Roman amphitheatre. The amphitheatre and art gallery will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 10 and Chapter 12.

Towards the end of Roman occupation Londinium was under constant pressure from Anglo-Saxon raiding parties. The Romans finally left Britain, due to attacks on Rome, in AD 410. The Saxons did not occupy the Londinium buildings left by the Romans but created their own settlements in the area, mostly to the west, and as the centuries passed the myth grew that many of the old buildings that were left had been put there by giants.

The amphitheatre site was clearly seen as important though. It is thought the Saxons held their citizen’s meetings or folkmoots there. The site was within the City walls, which had been re-fortified by King Alfred at the end of the ninth century, and perhaps on empty but still firm ground. This may have led to Guildhall eventually being built in the same area, as London within-the-walls fully re-established itself from the late Saxon period.

The word Guildhall suggests a connection with the guilds. These were, broadly speaking, trade organisations that were founded in the Middle Ages and are still flourishing today. The name ‘Guild’ may come from ‘gield’, an Old English word for ‘pay tribute’ and the original Guildhall might have been where taxes were collected. The word also comes from money – geld, gilt, gold.

If there was a direct connection to the guilds, there is a suggestion it might have been to the obscure Knighten Guild, which is mentioned by John Stow, the sixteenth century historian. The Knighten Guild was originally given special privileges by King Edward the Confessor in the eleventh century but was dissolved in the twelfth century and possibly absorbed by other guilds. Again, this is only a theory.

The original Guildhall was probably a small hall where the current west crypt is. Its other role was to host the ancient Court of Husting first mentioned in 1032 – though it was probably much older than that. This is where the Aldermen met, high-ranking officials whose name evolved from the Old English ‘ealdorman’ (the elder man), and was the supreme court dealing with administration and judicial matters. No records remain of the court, although we know it was held weekly by the mid-twelfth century. When the present Guildhall was finished in the fifteenth century they included the arms of Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), so they must have thought a building was there during his reign.

There was some sort of guildhall from around 1125, and by the reign of King John in the early thirteenth century there was a building that was the centre of administration. Very little is known about it. An 1128 summary of properties belonging to St Paul’s Cathedral also mentions a guildhall.

A second Guildhall was built probably around 1270-90 and it is thought it had three rooms. There are references to meetings in the Chamber of Guildhall and this is also where the city’s records and money were kept. Alterations were carried out in the 1320s and 1330s. It’s thought that today’s undercroft level was the ground floor, with the east end raised for a hustings (assembly) court – probably the present West Crypt. There may also have been an Upper Chamber and an Inner Chamber. The Common Council met in the Upper Chamber and the Mayor with the Court of Aldermen met in the Inner Chamber.

A chapel dedicated to God, St Mary, St Mary Magdalene and All Saints was built next to the Guildhall, to the south east, at the end of the thirteenth century. The main entrance was on Guildhall Yard. It was also associated with the Society of Puy, a brotherhood of the educated and wealthy who were dedicated to make London known for all good things. In the mid-fourteenth century a college of five priests, with a garden, was built to the south of the chapel.

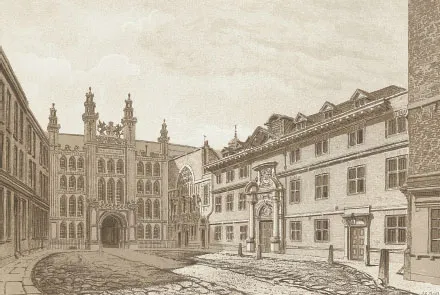

At the beginning of the fifteenth century the early Guildhall was more or less where the present one is. To the south was Guildhall Yard, with a gatehouse on its south side, giving onto Catte Street, later Cateaton Street, now Gresham Street. To the west of the gatehouse was the church of St Lawrence Jewry. To the east of the gatehouse was Blackwell estate and hall. Blackwell Hall was a large hall in which a cloth market took place, established in the late fourteenth century. To the north of Blackwell Hall on the east side of the Yard was the college of priests and next to that was the chapel.

One significant early event that took place in the old Guildhall was the celebration of the birth of the future King Edward III in 1312. The City of London held a festival for a week and in the last day of rejoicing the Mayor and Aldermen, all in their ceremonial robes, along with the Guilds of Vintners, Drapers and Mercers in their livery costumes, rode to Westminster to pay their respects. They then returned to Guildhall which was richly decorated and hung with tapestries. They had a banquet there and after dinner ‘went in carols’ through the City, for the rest of the day and long into the night.

King Edward III later went to war in France in what became known as The Hundred Years War. With the aid of City money his English armies defeated the French at the battles of Crécy and Poitiers. Before Crécy (1346) the City was worried about the possibility of a French invasion and protected Guildhall with ‘guns wrought of latten mounted on teleres and charged with powder and pellets of lead’.

Guildhall Porch, Chapel and Blackwell Hall as it appeared in the 1820s.

In 1363 under former Lord Mayor Henry Picard, the Vintners held a banquet for Edward III to celebrate his victories in France. Later the City played a part in the deposition of Edward’s grandson, King Richard II. The accusations of his misgovernment were read out in Guildhall.

In the fifteenth century King Henry V continued the English claim to the throne of France. There was a meeting in Guildhall between the Mayor, the Dukes of Bedford, Gloucester and York, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishop of Winchester and others to decide how the military campaign should be funded. This led to a question of precedence – who among all these dignitaries should chair the meeting? It was decided that the Mayor should, as the King’s representative in the City. The precedent was set and has been kept to ever since.

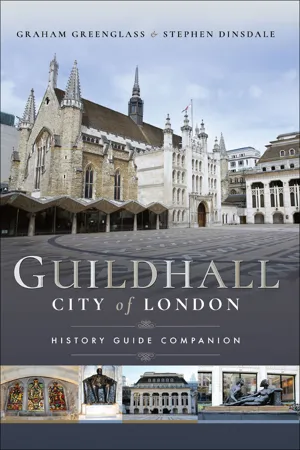

The Great Hall of Guildhall as we now see it, probably the third on the site, was started by John Croxtone in 1411 and mostly completed by 1430 in the Perpendicular Gothic style of architecture. Croxtone was not an architect – the profession did not exist then – but a mason.

It is the oldest non-ecclesiastical building in the City of London and is a Grade One Listed Building – a building of exceptional interest. It was the second largest Great Hall covered by a single-span roof in medieval England. Only Westminster Hall at the Palace of Westminster (part of the Houses of Parliament) is larger. A contemporary source, Robert Fabyan, described the previous Guildhall as ‘an Olde and Lytell Cotage’ but the new one he called a ‘fayre and goodly house’.

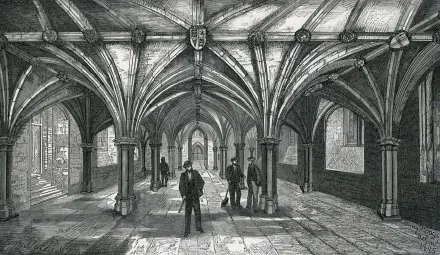

The western crypt – the crypt from the earlier building – had been retained and a new eastern crypt was built. The western crypt was probably used for City business while the new Guildhall was being built. The windows were enlarged to enable its expanded use.

Croxtone’s porch for the new building, on the south side, took the form of a large, elaborate church porch. The roof of the Great Hall was probably made of wood. There were two large windows, one at the west end and one at the east end. Beneath each was a raised dais, the east for the Hustings Court and the west for the Sherriff’s Court. Small doors led to corner turrets. Another door led to the room above the Porch. The architecture of the Great Hall is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5.

Lord Mayor Richard Whittington died in 1423 and his will paid for some of the paving – of Purbeck marble – and some of the window glazing. Other individuals donated money as well and when this ran out the City imposed surtaxes which lasted for about six years. Later a tax was levied on imported goods sold by foreigners. Foreigners did not mean people from other countries but meant traders who were not Londoners – for example, someone from Canterbury.

East Crypt, late nineteenth century.

![]()

Chapter 2

Agincourt to the Second World War

England’s winning streak of military victories continued during the first decades of the Hundred Years War against France. Following Guildhall banquets celebrating King Edward III’s victories at Crécy and Poitiers (1356) a similar banquet was supposedly held in 1420 to honour King Henry V, although well after the Battle of Agincourt...