- 64 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

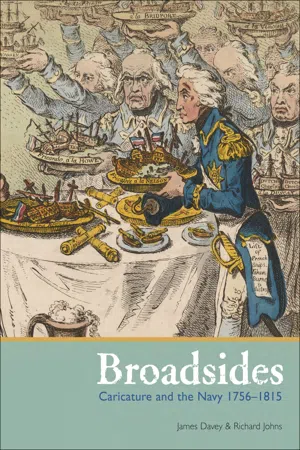

Broadsides explores the political and cultural history of the Navy during the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries through contemporary caricature. This was a period of intense naval activity encompassing the Seven Years War, the American War of Independence, the wars against revolutionary and Napoleonic France, and the War of 1812.Naval caricatures were utilised by the press to comment on events, simultaneously reminding the British public of the immediacy of war, whilst satirising the same Navy it was meant to be supporting.The thematic narrative explores topics from politics to invasion, whilst encompassing detailed analysis of the context and content of individual prints. It explores pivotal figures within the Navy and the feelings and apprehensions of the people back home and their perception of the former. The text, like the cariactures themselves, balances humour with the more serious nature of the content. The emergence of this popular new form of graphic satire culminated in the works of James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson, both here well represented, but a mass of other contemporary illustration makes this work a hugely important source book for those with any interest in the wars and history of this era.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Admirals

Since the time of Sir Francis Drake and the Armada, there has been a long history in the British Isles of celebrating naval heroes. Admirals who had honoured their rank and advanced the nation’s imperial and trading ambitions by leading the navy to victory in battle were rewarded with great riches and the peculiar distinction (rare in an age before mass media) of being recognisable to a large section of society, thanks to the circulation of news reports, biographical sketches and, above all, printed portraits. As the eighteenth century progressed, the individual achievements of Britain’s admirals also became a regular subject of caricature. When Gillray gave comic expression to a new canon of British heroes in John Bull taking a Luncheon, Admirals Howe, Nelson, St Vincent et al, joined the likes of Blake, Shovell, Benbow and Vernon in a line of naval champions spanning the previous two centuries. Increasingly however, it was scandal – often muddied by party politics – rather than success that attracted the attention of caricaturists. Those that failed to live up to the expectations placed upon them could expect to be pilloried; the slightest accusation of corruption, abuse of privilege or (more likely and most damning of all) of failing to engage the enemy, was met with the closest scrutiny from a ruthless and fickle, but always inventive press.

Isaac Cruikshank The Ghost of Byng Samuel Fores, 28 March 1808. Hand-coloured etching. NMM PAG8598

William Hogarth and Charles Grignion Mr Garrick in the Character of Richard III 20 June 1746. Etching with engraving. British Museum, Ee,3.121

Half a century after his execution, Byng’s memory was revived by Isaac Cruikshank in response to another military scandal. In The Ghost of Byng, the disturbing decomposing figure of the admiral, conspicuous in an old-fashioned uniform that even in 1808 signalled a bygone era, stands before Lieutenant General Whitelocke, an army officer court-martialled after failing to capture Buenos Aires (an action depicted in the framed image behind him). Whitelocke was cashiered for his troubles – a lenient punishment, suggests Byng, who returns from the grave to remind the world of his own cruel fate.

Cruikshank’s depiction of the startled Whitelocke recalls Hogarth’s earlier painting and print of the celebrated Shakespearean actor David Garrick as Richard III, but the overall subject was also inspired by a pamphlet that appeared two years after Byng’s execution. Presented as a tragi-comic conversation, the short text sees Byng’s ghost appear to defend his honour to another army officer, Lord George Sackville, who was himself court-martialled after refusing an order for a cavalry charge during the British victory at the Battle of Minden in 1759. Their encounter, as retold by the pamphlet’s anonymous author, was timely and to the point. When asked by Sackville why he had not pursued the French fleet, Byng replies defiantly that to beat an enemy ‘o’er and o’er again’ would be a ‘paltry Action, past Forgiveness’. Towards the end of the poem, Sackville’s thoughts turn towards his own impending trial (after which he too was cashiered), and to his public fate in the hands of the ‘filthy Mob’ with their ‘damn’d Lampoons and Satires’:

[Will] Printsellers and Gravers join

To maul this Character of mine,

And vilely stick me up and down,

In ev’ry Shop about the Town,

The Butt of ev’ry gaping Clown;

What must I say, what must I do?4

Byng’s reply is simple, if tinged with regret: pay the scurrilous writers and printmakers to work for you instead of your enemies.

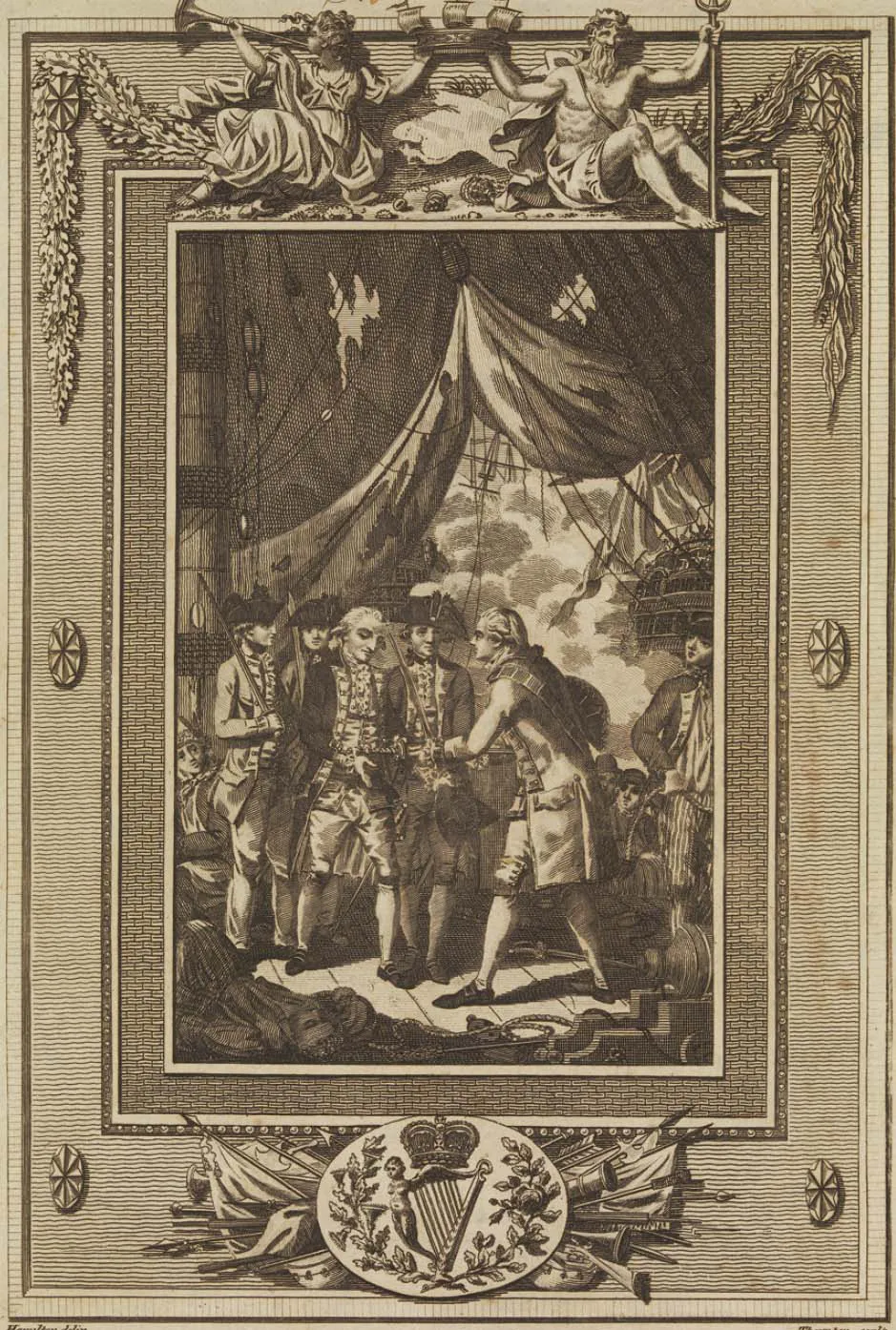

Count De Grasse delivering his Sword to the Gallant Admiral Rodney P Mitchell, 27 May 1782. Hand-coloured etching. NMM PAF3711

In the spring of 1782, Britain’s faltering efforts to defeat the rebellious colonialists in North America were temporarily boosted by Admiral Rodney’s decisive victory over Comte De Grasse, admiral of the French fleet at the Battle of the Saintes. Although it would prove to be a rare British victory in a war that was being lost elsewhere, news of Rodney’s Caribbean victory was greeted at home by public rejoicing and the popular refrain ‘Rodney for Ever!’.

De Grasse’s flagship the Ville de Paris, one of four French ships captured during the battle, provides the location for an ostensibly gentle satire on the manner of Rodney’s victory, in which the opposing admirals appear as physically contrasting but in all other ways equal opponents. ‘You have fought me handsomely,’ De Grasse declares with a bow as he offers his sword in defeat; ‘I was glad of the opportunity,’ replies Rodney, as sailors from both sides ‘huzza’ and toast the victorious British admiral.

In an age when the formality of naval battle and rules of engagement were faithfully observed, and protocols of surrender and parole meant that a defeated admiral could take comfort in refined conversation and a shared bottle of wine with his erstwhile enemy, Count De Grasse delivering his Sword also subtly confronts the notion that opposing officers had more in common with each other than with those among the lower ranks of their own side. By mocking the dull, patriotic prints that emerged after the battle, Rodney’s comic exchange with De Grasse, who had led the French fleet to victory at the Battle of the Chesapeake the previous year, appears at once triumphant and absurd.

William Hamilton The French Admiral Count De Grasse, Delivering his Sword to Admiral (now Lord) Rodney 1782. Etching with engraving. NMM PAD5388

Who’s in fault? (Nobody) a view off Ushant William Humphrey, 1 December 1779. Hand-coloured etching. British Museum Satires 5570

This anonymous printmaker holds no punches by depicting Keppel as a ‘nobody’ following his failure to defeat the French at Ushant in 1778. If ‘it’ has a heart, the inscription goes on to suggest, ‘it must lay in its Breeches’. Keppel’s failure intensified political divisions at home and polarised attitudes to the war. Another high-profile court martial of a naval commander (this time resulting in acquittal) was followed swiftly by Keppel’s resignation.

The Ville de Paris, Sailing for Jamaica, or Rodney Triumphant Thomas Colley, 1 June 1782. Hand-coloured etching. British Museum Satires 5993

Not everyone envisaged Rodney’s triumph at the Battle of the Saintes as such a gentlemanly affair. The Ville de Paris depicts a grotesque De Grasse on his hands and knees pulling a boat of French prisoners of war through the water towards Jamaica. On his back, a triumphant Rodney tugs at the defeated Frenchman’s ponytail and prods his sword at a broken and ‘discolour’d’ Bourbon flag as a makeshift British flag flies proudly from De Grasse’s improvised mizzenmast. Crude in its message and its technique, Colley’s print was produced, perhaps, as a hurried riposte to Mitchell’s overly polite caricature of recent events in the West Indies.

James Gillray Rodney introducing De Grasse Hannah Humphrey, 7 June 1782. Hand-coloured etching. NMM PAF3710

Rodney and De Grasse reappear in the first of a group of early political sketches produced by James Gillray and Hannah Humphrey. Rodney kneels in deference before introducing the tall and thin figure of De Grasse to a rotund George III. Standing to the King’s right, Charles James Fox laments Rodney’s success: ‘this Fellow must be recalled,’ he complains to the King, ‘he fights too well for us – & I have obligations to Pigot, for he has lost 17,000 at my Faro Bank’. On George’s left, Admiral Keppel recalls his own failed attempt to capture the Ville de Paris during the indecisive First Battle of Ushant in 1778. Against this backdrop of political discord and infighting within the navy, Gillray seems keen to promote Rodney as a patriotic figure – a commander who plays by the rules.

James Gillray Rodney Invested – or – Admiral Pig on a Cruize 1782. Hand-coloured etching. NMM PAF4156

Two weeks before the Battle of the Saintes, a new government restored Keppel to office as First Lord of the Admiralty. One of his first decisions was to remove Rodney as commander of the fleet in favour of Admiral Hugh Pigot; swapping a national hero for a commander who lacked experience and who was regarded by many as incompetent and corrupt. When new...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: Caricature and the Navy

- Chapter 1: The Admirals

- Chapter 2: Nelson

- Chapter 3: Jack Tar

- Chapter 4: Invasion

- Chapter 5: Politics and the Navy

- Notes and Further Reading

- Acknowledgements

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Broadsides by James Davey,Richard Johns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.