- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Truth About Rudolf Hess

About this book

Rudolf Hess' flight to Britain in May 1941 stands out as one of the most intriguing and bizarre episodes of the Second World War.In The Truth About Rudolf Hess, Lord James Douglas-Hamilton explores many of the myths which still surround the affair. He traces the developments which persuaded Hess to undertake the flight without Hitlers knowledge and shows why he chose to approach the Duke of Hamilton. In the process he throws light on the importance of Albrect Haushofer, one-time envoy to Hitler and Ribbentrop and personal advisor to Hess, who was eventually executed by the SS for his involvement in the German Resistance movement.Drawing on British War Cabinet papers and the authors unparalleled access to both the Hamilton papers and the Haushofer letters, this new and expanded edition of The Truth About Rudolf Hess takes the reader into the heart of the Third Reich, combining adventure and intrigue with a scholarly historical approach.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

The Work of Albrecht Haushofer

‘Rudi Hess and his equals are beyond help.’

Albrecht Haushofer’s letter to his father, 8 June 1932

‘I sometimes ask myself how long we shall be able to carry the responsibility, which we bear and which gradually begins to turn into historical guilt or, at least, into complicity …

There will be much violent dying and nobody knows when lightning will strike one’s own house.’

There will be much violent dying and nobody knows when lightning will strike one’s own house.’

Albrecht Haushofer’s letter to his parents, 27 July 1934

‘Perhaps we shall manage to chain the fuming titan to the rock.’

Albrecht Haushofer to Fritz Hesse after the Remilitarisation of the Rhineland, 1936

‘The disappointed fury over the missed war is now raging internally. Today it is the Jews. Tomorrow it will be other groups and classes.’

Albrecht Haushofer’s letter to his mother, 16 November 1938

‘The one good thing is that the free countries of the world still possess a vast preponderance of power which if compelled can be used as military force.’

Letter by Marquis of Clydesdale to Douglas Simpson of the U.S.A., 1 June 1939

‘There is not yet a definite timetable for the actual explosion, but any date after the middle of August may prove to be the fatal one. I am very much convinced that Germany cannot win a short war and that she cannot stand a long one.’

Albrecht Haushofer’s letter to the Marquis of Clydesdale, 16 July 1939. This was a clear warning as to when the Second World War was most likely to start and the letter was shown to Winston Churchill, to Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, and to the Foreigh Secretary, Lord Halifax

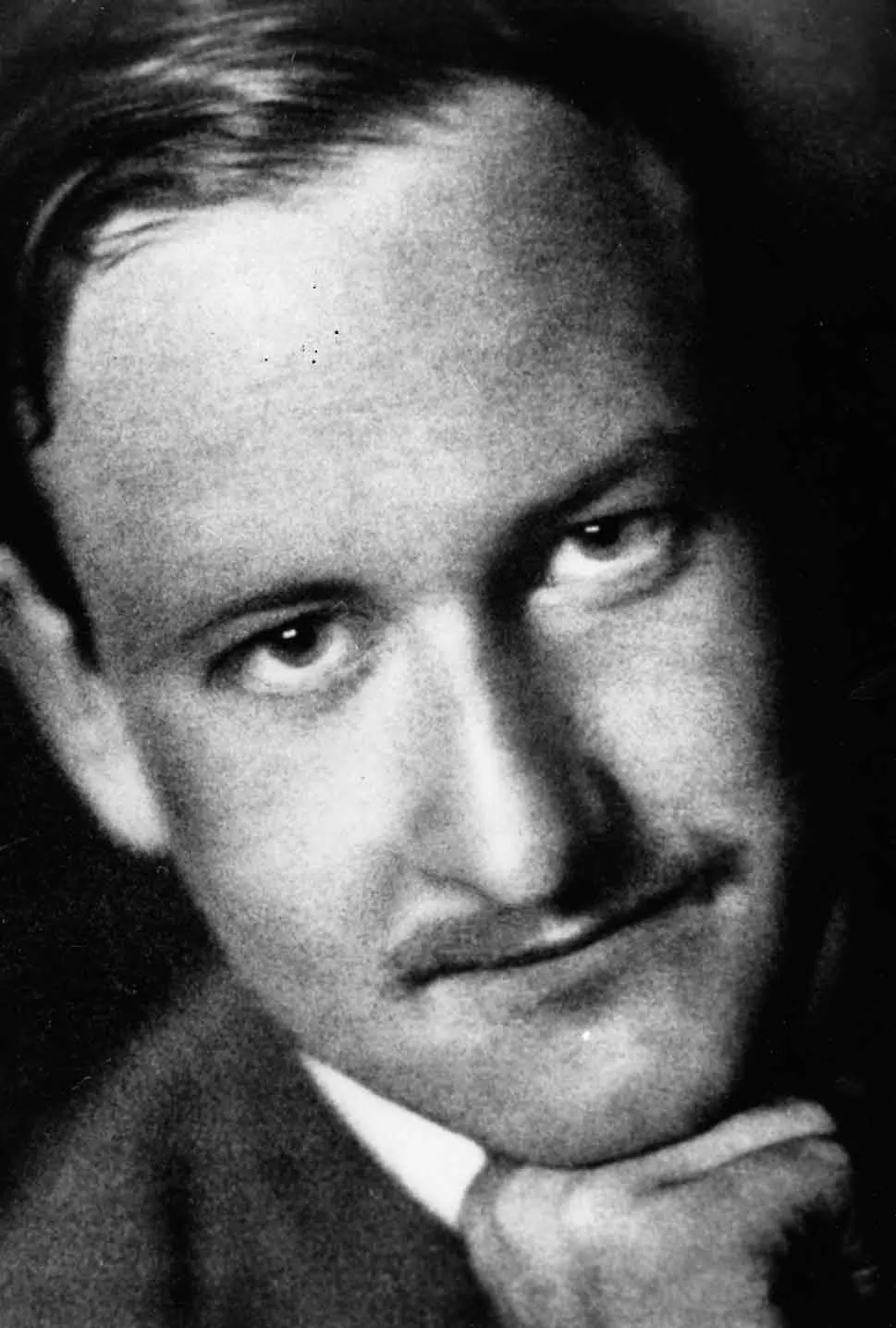

Albrecht Haushofer, the troubled German patriot of partly Jewish origin who passionately wanted peace between Britain and Germany. (Martin Haushofer)

1

Early Days

In 1933 Hess began to be influenced by Albrecht, Karl Haushofer’s eldest son. Although he could not know it then, Albrecht would decisively affect the course of his life a few years later.

Because of the unwitting role he was to play, Albrecht is a person worthy of close examination; he was certainly one of the most fascinating and mysterious of all characters lurking behind the scenes of the Third Reich. It was hard for his acquaintances to judge whether he was a scholar, geographer, poet, musician, playwright, resister of Nazism or staid official in the German Foreign Office, but all who knew him agreed that he was a man of huge ability. Allen Dulles wrote that Albrecht Haushofer ‘was fat, whimsical, sentimental, romantic and unquestionably brilliant’. It was said of him that his friendships were of an uncertain kind and that he would often put an end to them in a mood of angry despair. His friend Dr Carl von Weizsaecker wrote: ‘He could be compared to an elephant: weighty, clever, very clever and if necessary cunning.’

Albrecht Haushofer was much closer to his half-Jewish mother than to his father, the Professor General, with whom he did not always get on well. His father at times complained that his son would never make a German soldier, and the mother often had to smooth over relations between them. His letters to his parents tell a great deal, but it is his personal letters to his mother which are the most revealing, as he confided in her in a way which he did not with anyone else.

In 1917, at the age of 14, he attended the Theresien Gymnasium in Munich, where he was a solitary figure who did not integrate with his schoolfellows, mainly because they could not keep pace with him intellectually. One of his contemporaries asked him what he wished to become and without a moment’s hesitation he replied ‘German Foreign Minister’. Such confidence caused irritation amongst those around him, but they recognised that he had exceptional qualities. In 1920 several of his age-group were celebrating the end of the school term and Hermann Heimpel, a friend, leaves us a glimpse of this strange man:

Later Albrecht Haushofer made a great speech. He spoke of Germany, so full of love that it was unexpected, of the rest of the world, of stones and stars, of history and the future, with a dark seriousness as if he were carrying the wisdom of millennia and entering it in the book of the future: he spoke as if something was to happen. He appeared to be without hope, sombre and sweet. Since the others could not completely understand the speech but fully agreed with it they kept silent.

Albrecht Haushofer, as Secretary-General of the Berlin Society for Geography, welcomes Swedish author and explorer, Sven Hedin (on the right) at the station. (Hulton-Deutsch)

In 1924 at the age of 21 Albrecht Haushofer finished his studies in History and Geography at Munich University, passed his Doctor’s Degree summa cum laude, and submitted his thesis ‘Alpine Pass States’, which was not published until 1928. Many of his father’s ideas appear in it, but the word ‘geopolitics’ does not. Unlike his father he wished geopolitics to have the character of an exact science; it should not simply be a crude tool for political propaganda. Consequently, in most of his future writings he treated geopolitics and political geography as being on the same level.

Like many Germans he felt rootless and insecure in spite of his academic successes. He wrote to his mother on 25 May 1923: ‘But I am sometimes troubled, young as I am, by the thought whether I shall ever find a refuge, a home, or whether I shall always be and remain a rootless person, a bird of passage.’ In the summer of 1924 he went to Berlin and became assistant to the well-known geographer, Albrecht Penck. There, many doors were opened to him on account of his father’s reputation, and he grew into his father’s circle of contacts. In 1925 he became the Secretary General of the Berlin ‘Society for Geography’, a post which he held for the rest of his life, and in 1926 he became editor of the Periodical of the Society for Geography in Berlin. He lived at 23 Wilhelmstrasse, the premises of the Society for Geography, in an official flat on the top floor. During these years he travelled widely, visiting all the European countries, North and South America, the Near, Middle and Far East and the Soviet Union but it was his trips to Britain that he enjoyed most.

Politically Albrecht Haushofer was a Bismarckian patriot, with a hankering for a Constitutional Monarchy in the sense of an idealised Bismarckian State. He intensely disliked revolutionary movements, an attitude which had its roots in his memories of Munich in November 1918. At that time an attempt had been made by a group of leftist intellectuals, led by Kurt Eisner, to seize power in Bavaria by setting up a Socialist Republican Regime. The Wehrmacht had intervened and General Ritter von Epp, a friend of Karl Haushofer, put down the revolt, but not before hostages had been shot by the revolutionaries at the Luitpold Gymnasium. On 7 November 1928 Albrecht Haushofer wrote to his parents from Berlin: ‘That winter ten years ago means something to me which I shall never get rid of while I live – an inexhaustible source of hatred, distrust, anger and scorn.’

He also resented the Versailles Treaty and regarded the policy of fulfilment of the provisions of this Treaty as being too high a price for Germany to pay. As for the Treaty of Locarno of 1925, guaranteeing the frontiers of France and Belgium, he dismissed it sceptically as being ‘the seal affixed to an existing situation’ which would happily be broken by either side at the first opportune moment. He wanted a revision of frontiers and wrote in 1926 that a ‘lively participation of the German people, constructive and formulative, was not possible if present day frontiers are to be maintained’. The Polish Corridor driving a wedge through Germany was a particularly bitter grievance to him. ‘The present day solution of the Vistula problems,’ he wrote, ‘is unpleasant for Danzig, damaging for Germany and far from satisfying for Poland’.

Haushofer saw a future for Germany as a co-ordinating power in middle, east and south-east Europe, the area between the Baltic and the Adriatic, including the Baltic States, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the Balkan States. Situated between two powerful neighbours, Germany and Russia, these East European countries had traditionally fallen within the sphere of influence of either Germany or Russia. As German enclaves still formed an important part of the population in each of these states, Albrecht Haushofer saw them as potential clients of Germany in the economic field.

As a southern German who had a deep attachment for the Alps, he hoped that Austria and Germany would come closer together through a process of gradual evolution, until eventually an Anschluss would take place. In 1931 an attempt was made at the height of the Depression to form a German-Austrian Customs Union. The plan was thwarted through the opposition of France, supported by the countries of the Little Entente, and the International Court of Justice at the Hague rejected it.

This made Albrecht Haushofer regard France as the dedicated enemy of Germany. Had not France guaranteed the frontiers of Belgium, Poland and those of the Little Entente States, and was not France preventing Germany from collaborating with Austria and from exercising a decisive economic influence in south-east Europe? Was it not symptomatic of the desire of the French Government to want to prevent Germany from ever becoming a strong European Power and to keep her isolated?

He did not consider Russia as a possible target for armed aggression, or as a potential ally. The only country with which he wished close cooperation was Britain. In a letter to his parents dated 30 July 1930, he expressed his views on both Russia and Britain in a language which few Russians would have liked:

So my first impression of Russia is one of terrible poverty and oppression, a partly purposeless, partly systematic cultural decline of enormous proportions. On the other side the accumulation of sinister power and growing economic strength (partly through ruthless exploitation of large natural resources, partly however, through an undeniably systematic large scale reconstruction) in a few entirely or nearly barbaric hands.

The national character however has not changed. The Russian is still indolent, lazy, dull, unclean and unpunctual. Many things may be recognised in many fields: and the danger must not be underestimated.

To make common cause with Moscow is according to my impressions completely out of the question as long as the entire structure of our political mentality remains unchanged.

Britain fared much better in a letter dated 9 November 1939 written to his parents from London. From the way in which he expressed himself he was obviously enjoying himself, as though the seemingly self-confident British way of life was one to which he would have liked to belong, even if he did not wholly understand it.

And now London. General impression: envy for the country which still has so many men to steer her history.

I have at last seen almost all important leaders, to many of them I have spoken personally: e.g., Lord Allenby with whom I had a brilliant conversation for an hour without knowing who he was …

Splendid the old Earl of Crawford and Balcarres, a Scot of ancient descent – one of the wisest men I ever met … Chamberlain who actually makes a less distinguished impression: Churchill, who has become fat and looks more like a clever clown than a Statesman. … The German Embassy with the young Count Bernstorff and the young Prince Bismarck makes in comparison a rather paltry impression – the welcome was exceedingly cordial.

He idealised the British two-party system of government and saw in it a complete contrast to the Weimar Republic, which had been weakened through the frequent occurrence of party political splintering (he referred to President Hindenburg as the ‘sentry in front of the bankruptcy trustee’s office’). He especially liked what he understood to be British flexibility and pragmatism. He believed that ‘for every political aim there are hundreds of forms; but he who insists on sticking to one will be stunted’. He thought that an appreciation of this outlook had been the key to the successes of Bismarck and the British.

To Haushofer’s way of thinking co-operation with Britain was essential and any war in Europe unthinkable. In any large-scale war there could not in his view be any victors – only death and destruction. I...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- The New Foreword 2016

- Introduction

- Prologue

- Part I: The Work of Albrecht Haushofer

- Part II: The Hess-Haushofer Peace Feelers

- Part III: The Fate of Albrecht Haushofer

- Epilogue

- Afterword

- Appendix I: The Sonnets of Moabit by Albrecht Haushofer

- Appendix II: Further Releases of Classified Material

- Sources and Select Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Truth About Rudolf Hess by James Douglas-Hamilton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.