- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A worthy tribute to the John Brown company and to British shipbuilding . . . a joy to enthusiasts of the great ships of the past."—Australian Naval Institute

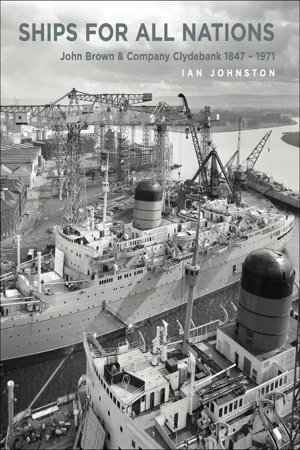

The Clydebank shipyard built some of the most famous vessels in maritime history—great transatlantic liners like Lusitania, Queen Mary and QE2, and iconic warships like the battlecruiser Hood, and Britain's last battleship, HMS Vanguard. Starting life as J & G Thomson in 1847, the business acquired its more famous persona when taken over in 1899 by the Sheffield-based steelmaker John Brown & Co, which enhanced the yard's existing reputation for turning out first-class products, both naval and mercantile.

This book charts the fortunes of the company in terms of its business development, its management and personnel, as well as the great variety of ships it built during the century and a quarter of its existence. It also tells a wider story of the rise to world domination of the British shipbuilding industry and its eventual decline and collapse in the post-war decades, as reflected in the experience of John Brown.

Written by an acknowledged authority on Clydeside shipbuilding, the book was originally published in a limited edition in 2000, but this reprint is entirely new and revised, although it retains all the original photographs from the yard's own unrivaled collection.

"Essential to anyone's maritime collection."—Sea Breezes

"The profusely illustrated, beautifully produced and very detailed story of John Brown & Company."— Army Rumour Service

The Clydebank shipyard built some of the most famous vessels in maritime history—great transatlantic liners like Lusitania, Queen Mary and QE2, and iconic warships like the battlecruiser Hood, and Britain's last battleship, HMS Vanguard. Starting life as J & G Thomson in 1847, the business acquired its more famous persona when taken over in 1899 by the Sheffield-based steelmaker John Brown & Co, which enhanced the yard's existing reputation for turning out first-class products, both naval and mercantile.

This book charts the fortunes of the company in terms of its business development, its management and personnel, as well as the great variety of ships it built during the century and a quarter of its existence. It also tells a wider story of the rise to world domination of the British shipbuilding industry and its eventual decline and collapse in the post-war decades, as reflected in the experience of John Brown.

Written by an acknowledged authority on Clydeside shipbuilding, the book was originally published in a limited edition in 2000, but this reprint is entirely new and revised, although it retains all the original photographs from the yard's own unrivaled collection.

"Essential to anyone's maritime collection."—Sea Breezes

"The profusely illustrated, beautifully produced and very detailed story of John Brown & Company."— Army Rumour Service

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | Set in Motion 1847–71 |

The events that placed Clydeside in a position of world prominence in marine engineering and shipbuilding were underpinned by interrelated developments. The emergence of the iron industry in the mid-eighteenth century using locally-mined ore served as a starting point. The Carron ironworks near Larbert, established in 1760, is generally regarded as the beginning of the modern Scottish iron industry. In 1782, the Clyde ironworks began production to the northeast of Glasgow. These developments encouraged exploitation of the Lanarkshire coalfields, leading to a significant mining industry. In addition, Glasgow already had an important textile industry first established with flax spinning and then, by the end of the eighteenth century, further consolidated with cotton. By 1840, the population of Glasgow numbered 255,000 and the city rivalled Manchester as a cotton spinning and weaving centre. These industries, of recent introduction in themselves, were soon to be eclipsed by the engineering products of the new iron industries which they had indirectly spawned.

The machinery employed in the textile industry was generally not of local manufacture and this encouraged a number of millwrights and iron founders, working in and around Glasgow, to specialise in the repair and manufacture of spares for these machines. From these modest beginnings, the design and manufacture of textile machinery were undertaken. This had the twin effect of stimulating the growth of iron foundries in the Glasgow area and, at the same time, creating a pool of skilled metalworkers. However, it was the commercial development of steam navigation that provided the impetus for the next series of developments in the growth of engineering.

Comet was launched in 1812 and sailed successfully until wrecked in 1820. She was 42ft long × 11ft beam × 5ft 6in deep and built of wood. Her 3hp engine was constructed by John Robertson and her boiler by David Napier.

In August 1812, when Henry Bell made his historic voyage down the Clyde in the Port Glasgow-built Comet, it was with a steam engine designed and manufactured by John Robertson in Glasgow and a boiler made by David Napier in Glasgow.1 While others had built steam engines for marine purposes, most notably William Symington with the successful Charlotte Dundas of 1803, it was the Comet and its three-and-a-half-hour pioneering voyage covering only twenty or so miles from Glasgow to Greenock which beckoned new horizons in marine transportation. Steam-powered machinery had made a small but significant impact on the vagaries of sail, wind and tide.

While there was little new about the nature and function of ships, driving them through the seas by mechanical propulsion was novel. By 1816, no fewer than twenty steamboats were plying the Clyde with machinery ranging from 6hp to 30hp.2 Of these twenty vessels, five were built at Dumbarton, twelve at Port Glasgow and three at Greenock; all were of wooden construction. The engines for all but two of these vessels were made in Glasgow, and the remaining two were both the product of James Watt’s firm in Birmingham. Although Glasgow had as yet played little part in the construction of vessels, it was through steam propulsion and engine building that the city’s association with shipbuilding was established.

David Napier and his cousin Robert are widely recognised as having laid the foundations of marine engineering and shipbuilding on Clydeside. David Napier, two years older than his cousin, established his first engine works in 1816 at Camlachie in Glasgow. An engineer of considerable talent and ingenuity, he perfected the steeple engine employed in many early steamers. Napier moved from Camlachie and set up new engine works at Lancefield Street, west of the city centre, in 1821, leaving the old works to the equally-talented Robert.3 At this time, David Napier employed John Wood and other shipbuilders in Port Glasgow to build hulls for his engines. By 1835, David had abandoned Clydeside and was running a successful business in London, and Robert had taken over the Lancefield engine works. The success of the marine steam engine in propelling ships soon encouraged others to establish themselves as engineers and engine builders. The role of both David and Robert Napier in training a cadre of talented engineers and shipbuilders in their works at Lancefield and later, at Govan, cannot be underestimated. Distinguished shipbuilders such as David Tod, John McGregor, William Denny, John Elder and of course the subjects of this book James and George Thomson were under the tutelage of Robert Napier at the outset of their careers.

A Navigable Channel

The development of shipbuilding in Glasgow and the upper Clyde was inextricably linked with the development of Glasgow harbour and the River Clyde. In 1800, the upper part of the river was barely navigable by vessels drawing more than 3ft, which effectively prevented ships of any reasonable size sailing to Glasgow. To some, the solution lay in bypassing the Clyde altogether. In 1806, work started on the construction of a canal linking Glasgow to the Ayrshire coast at Ardrossan. By 1810, the money had run out, leaving only an eleven-mile section of canal from Glasgow to Johnstone and the city with no meaningful access to the sea.4 It was largely down to the far-sighted efforts of the River Improvement Trust, constituted in 1809 by Act of Parliament, that both widening and deepening operations were carried out over a long period of time with the aim of making Glasgow accessible to ocean-going vessels.5 This process made it possible for ships of similar size to be built there. The first builder of ships of a reasonable size in Glasgow was John Barclay, later to become associated with Robert Curle, who established a small slip and yard for building and repairing wooden vessels at Stobcross Pool in 1818.

It was the advent of iron, rolled into flat plates as a shipbuilding material, which distinguished the rise of shipbuilding on the upper part of the Clyde. The realisation that iron would enable ships of much larger dimensions to be constructed, in addition to offering a more rigid structure for steam engines, provided the stimulus for development. Heavy cast-iron engines fitted into wooden hulls, no matter how well built, were a marriage of limited future. It was the combination of iron hull, steam engine and commercial incentive that enabled the Clyde to rise to a position of prominence in marine engineering and shipbuilding.

There were many shipyards throughout the UK building wooden ships, although few had experimented with iron. The first builders of iron ships on a regular basis were not far-seeing builders of wooden vessels but the engine builders who saw hulls constructed of iron as a natural extension of their existing metalworking skills. Among the first to exploit this new development in Glasgow were Tod and McGregor, later described as the ‘originators of iron architecture as applied to the construction of vessels’. In 1839, they set up an iron shipyard at Greenlaw on the south bank of the River Clyde, having previously built a number of small iron vessels at their Clyde foundry on the north side of the river.6 Robert Napier, assisted by the talented marine engineer David Elder, entered iron shipbuilding at an early stage, taking over McArthur and Alexander’s shipyard at Govan in 1842. Within a very short space of time, Napier became the most important of the early Clyde shipbuilders. Thus, the second phase in the development of shipbuilding on the upper Clyde began with the evolution of marine engineers into iron shipbuilders. This phase is described by the following comment, which appeared in the North British Daily Mail on 26 March 1853:

Out of a hundred or more vessels now being constructed on the Clyde there are only seven of wood: and of all the rest ninety-four are steamers. There can be little doubt that the time is hastening fast when timber ships will be obsolete, and that the world’s traffic will be conducted mainly by steam as an auxiliary power to the uncertain and precarious winds.

It is a curious phase in the art and mastery of shipbuilding, that hitherto nine tenths of these vessels made of iron have been built by engineers who never studied naval architecture, and all at once took a lead in the art, leaving the professional shipbuilders to jog on at heckmatock and oak, until they were distanced in the race of competition and had to convert their adzes into huge iron shears, and their augers into punching machines, in self defence. And yet it is a study to see how soon carpenters became cunning in bending plates, and shipwrights in fashioning angle iron.

Henry Bell (1767–1830) placed the contract for the steamer Comet with the Port Glasgow shipbuilder John Wood & Co. Bell, a millwright by trade, had Comet built to take passengers from Glasgow to Greenock and Helensburgh three times a week, thus inaugurating the first successful steamship service in Europe.

The first steamship to cross the Atlantic was the wooden-hulled Sirius, which had side-lever paddle engines constructed by Thomas Wingate of Glasgow. As the Clyde emerged as an iron shipbuilding centre, it was by no means the only one of importance. Much of the shipbuilding industry was concentrated on the Thames and for a time, thanks largely to the exertions of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and ships such as Great Britain and Great Western, it seemed as if Bristol might also develop into a major shipbuilding centre.

An early image of industrialisation on the Clyde painted in 1840. It shows the wood shipyard of John Barclay to the west of Finnieston Quay.

There can be little doubt that great excitement must have been generated by the promise of this new industry, the products of which brought far-off places a little closer through reliable, swifter, mechanical propulsion. The creation of engine works, boiler shops, forges, foundries, yards and a host of related industries in its midst set Glasgow on the path to becoming the major centre of heavy industry, which it would remain for more than one hundred years. Of the men who developed this industry, the Mechanics Magazine said in April 1853:

…...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Set in Motion 1847–71

- Chapter 2: Relocation and Expansion 1872–99

- Chapter 3: Forging Ahead 1900–13

- Chapter 4: The Great War 1914–18

- Chapter 5: An Empress, Two Queens and a Duke 1919–38

- Chapter 6: The Second World War 1939–45

- Chapter 7: Post-War Boom and Bust 1946–72

- Appendices

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ships for All Nations by Ian Johnston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.