- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The First World War was an event so important, so catalytic, so transformative that it still hangs in the public memory and still compels the Historians pen. It was a conflict which, by the end of the struggle, had created a world unfamiliar to the one in existence before it and brought levels of destruction and loss all too unimaginable to the generation of minds which created it. Despite this, we still find it hard to picture what it was like to live through this war. Right from its start, Mabel Goode realised that the First World War would be the biggest event to take place in her lifetime. Knowing this, she took to recording it, taking us day by day through what living in wartime Britain was like. The diary shows us how the war came to the Home Front, from enrolment, rationing, the collapse of domestic service and growth of war work, to Zeppelin attacks over Yorkshire, and the ever mounting casualty lists. Above all else, Mabels diary captures a growing disillusionment with a lengthening war, as the costs and the sacrifices mount. Starting with great excitement and expecting a short struggle, the entries gradually give way to a more critical tone, and eventually to total disengagement. The blank pages marked for 1917 and 1918 are almost as informative as the fearful excitement captured at the onset of that tremendous conflict. This is a strong narrative of the war, easy to read, mixing news with personal feelings and events (often revealing gap between official news and reality). Also included are several poems written by Mabel and a love story in the appendix, giving a complete insight into the life of the diarist. Of note is the fact that Mabel and her brothers (the main serving protagonists in the diary) lived in Germany for some time, meaning they could all speak German and knew 'the enemy nation' as many Britons did not.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

The Disappearance of the Spirit of 1914

‘It takes 15,000 casualties to train a major general.’

Attributed to Marshal Ferdinand Foch

In order to understand the metamorphosis the war underwent and how different its growth was to expectations, we must look at the diary’s opening and the spirit with which the country went to war. There is considerable debate about the spirit in which the British people responded to the outbreak of war and its early days. What emerges from the opening passages of the diary, however, is remarkably strong and consistent. Mabel is engaged with, and enthused by, the reports coming from the continent. She eagerly embraces news of the nation readying itself for war. It would not be impossible to say that the whole thing enthrals her.

The excitement of the start

Mabel might not have known what lay ahead in 1914 but she certainly realised the war’s significance as the most important event to happen in her lifetime. This is immediately apparent in the diary’s opening lines: ‘Never has there been anything so tremendous in the History of Europe’.1 Referring to the war as ‘long expected’ in her first entry on 11 August hints at just how pregnant the summer of 1914 was with the struggle. The care and attention Mabel gives to the outbreak of war and the beginning of her diary to record its events is indicative of the seriousness with which she and others took the news. The rapid unfurling of the two fighting blocs and the hasty mobilisation of troops – the sheer swiftness of the start of the war – is captured in the pace of Mabel’s early entries. We see the growing momentum of events, as Mabel notes on 18 August that the news was developing faster than the newspapers could keep up with: ‘Several editions of the ‘Press’ have been published every day at short intervals ever since the war began’. To Mabel, the war merited putting pen to paper because it was both apprehensively awaited and utterly thrilling as it developed day by day.

A short war?

Mabel clearly thought the war would not last long. On 30 August 1914 – twenty-nine days after the war started – she wrote that the news sounded like the ‘beginning of the end’. Initially, Mabel held onto this belief. On 12 September she wrote ‘one really does not see how the War can go on very much longer. The French say it will be over by Christmas. It seems quite likely’. Not alone in this, she noted earlier, on 8 September, that Major Sharpe (one of her brother’s senior officers) ‘thinks the war will last 6 months’. Not all of the voices were so optimistic; her brother Henry felt the war would last a year, but Mabel dismissed this, having written on 12 September that ‘the wish is father to the thought. … he is anxious for the war to last, or rather, to get out [to France] before the war ends’. It is only as the war went on that Mabel started to question the prospect of a short conflict. The first sense of this came on 1 November: ‘The War has been going on for nearly 3 months now, & it seems likely to be longer than ever’. Passage after passage reveals how Mabel increasingly doubted that the war would be over by Christmas: a process that shows the gradual death of the excitement and optimism that characterised the Spirit of 1914. In an entry on 30 November, Mabel records that Henry and a servant are tucking up the car ‘for its long rest’ and then, giving a sense of growing doubt and caution, she decided to add ‘How long? I wonder’.

Why Britain went to war and who she was fighting

As the illusion of a short war was shattered, so was Mabel’s perception of the Germans. In the Spirit of 1914, Mabel draws strength from a feeling that the war was righteous; writing on 18 August that ‘It is a great thing to feel that our cause is a just one & one may genuinely believe that God has helped us, for things are wonderfully in our favour. … It is the cause of progress, peace & civilisation against militarism & despotism’. Viewing why we went to war in these terms helps contextualise the patriotism expressed on the outbreak of the conflict. To Mabel, it seemed that the war was distant and unthreatening and that the enemy could be managed and defeated. On the suggestion of an invasion threat, Mabel wrote on 21 August 1914 that, given the forces on the Western and Eastern Fronts, ‘one can only think they [the Germans] will have all they can do not to be completely crushed’. Again, her tune starts to change by 7 May 1915; after writing about German artillery, Mabel admits that ‘They are a more formidable foe than I expected’, a sentiment which must have been shared by many.

Escalation from stagnation

The tragedy of a large-scale and ground-breaking conflict like the First World War is that it becomes like a ratchet that can only be turned one way: it locks itself into intensification as more and more die in its battles, making negotiation and peace less and less likely, because leaders must convey that those deaths were not in vain. Thus, ever-increasing resources and people are spent on an all-out victory to justify the cost which, when done by both sides, leads to nothing but further spiralling. If half measures were ever an option, they could not survive in such a climate. That was the nature of this war.

Mabel had a real sense of the role technology would play in changing the parameters of this war. She wrote on 25 October 1914 that ‘The great battle on the Belgian coast is still in progress, the first in history in which there has been fighting on land, on sea & in the air all at the same time’. She had known smaller-scale colonial conflicts through one brother (Stuart) being a professional soldier and the other (Henry) serving as a surgeon in the Boer War. However, the extent to which new technology would allow this war to dwarf the scale of what had been before was yet to be seen.

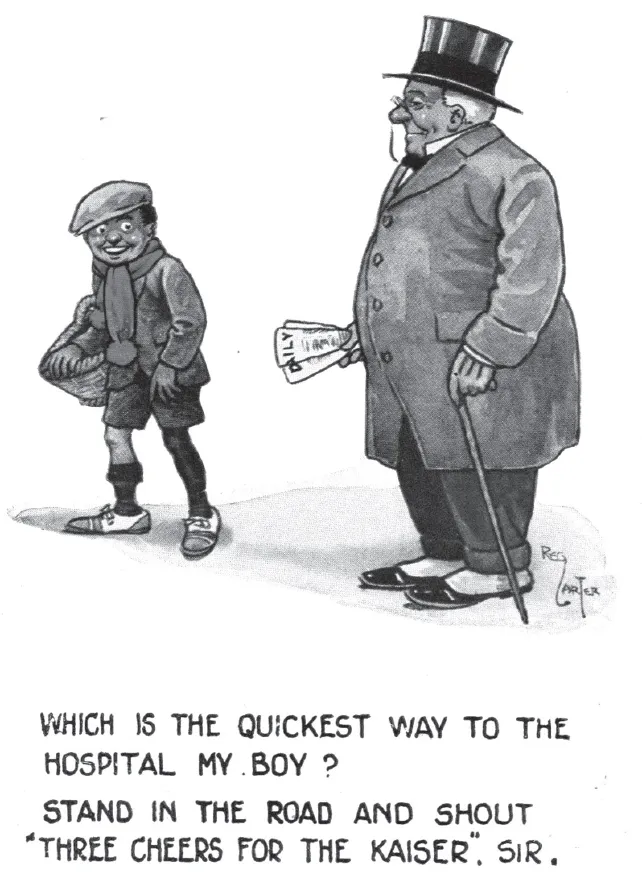

The evolving nature of the war, transformed through industry and technology, led Mabel to write of new and ghastly evils (seemingly a world away from the noble sentiments illustrated in figure 4). She mentions the growth of industrial chemical warfare as early as 7 May 1915 with the comments:

The effects of the asphyxiating gas used by the Germans near Ypres is too horrible. Those who do not die at once, suffer from slow, increasing suffocation, lasting sometimes one or 2 days … It is the most horrible form of scientific torture. And those who do not die from the suffocation, always suffer from acute pneumonia. What fiends they are! They say half the soldiers who came into hospital suffering from gas only, quite unwounded, have died.

When the war came to civilians, Mabel condemned the German behaviour and, on 16 May, recorded how this changed the public feeling about the war, saying:

This cold-blooded murder of civilians at sea & the use of the poisonous gases have quite altered the feeling of our troops towards the Germans. Before there was a good-natured dislike & tolerance, but now there is a bitter hatred & a demand for reprisals.

Figure 5: Making light of the growing anti-German sentiments in wartime Britain. (Tony Allen’s WWI Postcard Collection)

Indeed, the horrors of the escalating war, and an increasingly desperate Germany, did lead to reprisals and spontaneous public anger (made light of in figure 5). Mabel went on to mention in the same entry that ‘Since Lusitania was sunk there have been many anti-German riots & shops wrecked & large numbers of the enemy aliens have been interned’.

The mounting casualty lists

As the war changed, so did the public’s perception of it. Essential to this process was the fact that as the war enveloped more men, it became personally significant to more and more families up and down the country who now had a relative fighting. The diary gradually traces this growing realisation that the war will be a longer, harder and altogether more desperate affair than expected. The turning point seems to come alongside a tangibly more intense anxiety for Mabel’s brother’s welfare. On 16 May 1915 she wrote: ‘it is indeed a terrible war & it will be almost a miracle if he [Henry] comes back unscathed’.

Typical for families across the nation, this fear of loss added a personal concern to the frustrating lack of progress Mabel mentions time and time again. On 27 June 1915, Mabel sums up her feeling that the war was both costly and futile: ‘One must admit that we have not got very far yet in moving the Germans either East or West’, adding: ‘Our losses each day are terrible, both officers & men. Generally between 100 & 200 officers every day in the Casualty List, & yet so little to show for it!’ This feeling lingered, as she adds nearly a month later on 26 July that ‘the West side is practically in status quo’. In marked contrast to the excitement of the first few entries of 1914, these unhappy observations give way to critical comments, almost certainly aided by the fact that Mabel’s brother was now in uniform. On 1 August 1915, Mabel wrote: ‘We seem quite unable to do more than hold them. I suppose on account of want of guns & shells. It has been a most disappointing year on the West, to my mind’.

Mabel’s thoughts were, however, not entirely negative. She added ten days after this entry that it was the Allies, not the Central Powers, who could ultimately sustain a longer war. What would prove to be her, largely vindicated, thoughts on the balance of resources encouraged her to believe that the Germans’ ‘turn will come’. Nonetheless, the incompetent handling of the battles around Salonica (which failed to prevent the fall of Serbia), provoked Mabel to write on 28 November 1915 that ‘We always seem to leave things to fate & suddenly wake up when the harm is done, instead of preventing it. Another terrible waste of valuable lives & time.’

Disengagement

Even as the war’s longevity surpassed expectations, all Mabel could do on hearing the latest news was to conclude that it would last longer still. On 25 August 1914, Mabel wrote that the Allies had failed to decisively deal with the enemy: ‘So the first important news is bad just when we had hoped that the Allies would have inflicted a crushing defeat on the Germans. It is sad, as it will certainly prolong the war’. On 1 November 1914 she recorded Turkey’s coming in against the Allies and the Boer rebellion, stating ‘Of course all these things will lengthen the war’. By 6 June 1915 the shell shortage worried Mabel a great deal, as she recorded ‘I fear it will very much prolong the war & cause terrible loss of valuable lives, all alas! our best’. A little later, on 27 June 1915, the bad news from the Eastern Front again pushes victory further away from Mabel, who wrote: ‘The Germans & Austrians under General von Mackensen have retaken Lemberg, which was taken by the Russians as long ago as September 2nd. Of course they are rejoicing greatly. It will certainly lengthen the war & cheer our enemies, which is very unfortunate’. This is reinforced on 1 August 1915 when the losses on the Eastern Front cause Mabel to write again: ‘It is a great triumph for the enemy & will doubtless lengthen the War very much’ and on the 11 August ‘Of course it will lengthen the war’.

The unfolding events Mabel recorded progressively blotted out her hopes of a swift victory. The spectre of sustained Allied defeats was so alien to the expectations of the general British public at the start of the war that the optimism, which characterised the Spirit of 1914, was forced to eventually give up the ghost. To a woman who had been born into the certainty and selfconfidence of Victorian Britain at its imperial apogee, the lengthening war must have stretched ever forward into a new and more frightening world.

As Mabel saw the war lengthen, so she saw it change. She saw it emerge as a struggle worse than anything she and her peers had imagined. She saw the costs mounting and the failure to make gains in spite of tremendous effort and sacrifice. As with so many others, the spirit of enthusiasm and excitement, evident in the diary’s early passages, faded. What replaced them, in Mabel’s case, was a mixture of confusion at the handling of the war, bitterness towards an enemy that seemed to turn its back on the rules of the game, and criticism of a lack of Allied progress. All of these things fed into one growing theme: apathy. Just as the above entries demonstrate Mabel’s change of tone, as the Spirit of 1914 is eroded, so the chart in figure 6 shows that, as the war went on, she paid less attention to her diary. Each year the gap between entries steadily increases, and those terser, gloomier entries of 1915 and 1916 look increasingly different from the sort of language used in 1914.

While the diary gives us much more than a personal insight into that sapping of the Spirit of 1914, it is the despondency evident in its pages which is the major message we can take from Mabel. As time, blood and funds are spent, the view from Mabel’s Home Front turns away from whole-hearted patriotism, firstly to a questioning of management, then to a loss of interest and finally to a general disengagement. Entries were written further and further apart and with less enthusiasm until, eventually, they stopped altogether.

Figure 6: Gap between entry dates. (The spike in early 1916 is linked to the death of Mabel’s mother.)

Comments from the final few entries set the tone, as Mabel observed on 29 October 1916 that ‘It is too wet & muddy now for the Allies to make much progress in the West, though they continue to move forward. Henry says they think the War may last another 2 years’ and from the final passage: ‘With Roumania in German hands, the war may go on another 3 years, apparently’. Mabel sums up the whole picture in the silence of the empty pages where the 1917 and 1918 entries should be. That silence is the furthest she got, and could get, from those long, detailed and upbeat opening entries.

Mabel’s final entry in 1916 also gives us a fascinating insight into something we now find very hard to understand: what it was like to live through ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Selected List of People Featured in the Diary

- Introduction: A Short Diary of a Lengthening War

- Chapter 1: The Disappearance of the Spirit of 1914

- Chapter 2: Worlds Apart: Mabel’s View and the Reality

- Chapter 3: Roles Vanished, Roles Remade

- Chapter 4: Total War

- Chapter 5: About the Diarist

- Chapter 6: The Brothers Goode

- Chapter 7: What we Have: Objects with a Story

- Chapter 8: Mabel Goode’s Diary of the Great War: 1914

- Chapter 9: Mabel Goode’s Diary of the Great War: 1915

- Chapter 10: Mabel Goode’s Diary of the Great War: 1916

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Lengthening War by Michael Goode in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Biografie in ambito militare. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.