![]()

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

PART ONE

THE BATTLE OF THE IMJIN RIVER

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER ONE—22nd April, 1951

CHAPTER TWO—23 April, 1951

CHAPTER THREE—24th April, 1951

CHAPTER FOUR—25 th April, 1951

PART TWO

UNEASY LEISURE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

![]()

FOREWORD

by

MAJOR-GENERAL T. BRODIE, CB, CBE, DSO

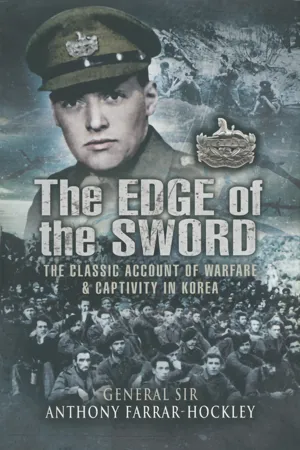

THIS book is the story of The Glosters in the Imjin Battle in Korea.

It is also the story of how officers and men of the Glosters, Ulster Rifles, 5th Fusiliers, 8th Hussars, Gunners, Sappers, Doctors and Padres fought, not only in the battle, but again in captivity under appalling conditions and with inhuman captors.

Captain Farrar-Hockley, then Adjutant of The Glosters, who himself was outstanding in the battle and afterwards, has written the most graphic account of a battle and of escapes from captivity I have ever read.

This is a book which ought to be read by every soldier and prospective soldier.

Here he may learn what is meant by real discipline and inspiring leadership, of the part played by Regimental traditions and the Regimental spirit in proper units, and to what heights men can rise because of them.

He, and the civilian too, may see why the British have still got something that the rest of the world envies.

I am indeed honoured to be asked to write a foreword to this book. I am prouder to have known so well all the officers and men mentioned in it.

Headquarters

1st Infantry Division

MELF. 27

![]()

![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

THE BATTLE OF THE IMJIN RIVER![]()

PROLOGUE

THERE had been no movement along the entire Battalion front for days, but for an occasional old, white-robed Korean peasant, too rooted to his land to be transplanted by war.

No movement along the northern bank of the winding Imjin River, now lazy, slow, and somnolent in the dry April.

No movement upon the red Sindae feature where Terry and Alan had sought and found the enemy standing patrols, since vanished; nor yet across the Gloster Crossing among the hills, where we had searched so diligently with the tanks of the Eighth Hussars —a fruitless, two-day search across twelve miles of No-Man’s Land, looking for an enemy with whom to do battle.

No movement.

And yet, of course, they had not gone. The push north across the Han River had but temporarily defeated them; for they were so many and we so few. Now they had withdrawn far, far beyond our reach, to gather for another blow; to draw fresh multitudes from China’s wealthy manpower account; to fill their forward magazines and armouries; to fan their forces’ fury for the fight with yet another tale of lies.

And so we waited; and as we waited, so we watched.

Forward on Castle Hill, commanding the long spurs that rose almost from the southern bank of the river, holding in part the hard dirt road that ran through the cutting along their right flank, was A Company, Pat’s boys, so like the rest in that they were a mixture of both seasoned and green men; in that they knew themselves to be, assuredly, the best men in the whole Battalion. Yet different, in that they were stamped by Pat’s own character, and marked by their own past record in battle and at rest.

Across the road, laying claim to some of the houses of Choksong, whose dwellings straddled it, was D Company, guarding the eastern flank of the road that led from the river: the road which crossed Gloster Crossing to wind north among the hills through countless villages and hamlets to the broken streets of Sibyon-ni. Spread forward along a feature just higher than Castle Hill, D Company patrolled forward with A Company nightly and watched by day the hills and valleys across the river bank. From this high hill, Lakri would descend to meet Pat on the neutral ground of the road before repairing to a hut in either’s territory for a cup of tea and, when this needed justification, a co-ordinating conference.

At the top of the pass, the road curved west before descending again to divide in the broad valley behind Pat’s defences. One fork continued to the south, entering the hills once more between high cliffs on whose western crest Spike’s Pioneers secured Hill 235. And to the east, from where the gorge began, C and B Companies were disposed with their backs to the jagged crest of Kamak-San that towered above all other features within sight.

Sam’s flock—Support Company—was ever a scattered one; no less around this Choksong defensive position than elsewhere. For Spike’s platoon were infantry; the anti-tank platoon were jacks-of-all-trades; Theo’s machine-gunners were scattered about the hills where their sturdy, reliable water-cooled Vickers might pour their fire to best advantage into an attacking force. Only Graham’s mortars were concentrated; the square pits dug in between the road and the stream that ran behind C Company to turn ninety degrees by the ford, from where it ran across the valley north to Choksong. And on either side of the ford lay Battalion Headquarters.

Here stood the weathered old Command Vehicle, Haskell’s pride, so like the Grand Old Duke of York; around it the signals vehicles and Guy’s gunner GMC. Here was the Regimental Aid Post, where Bob dispensed medicine on all days and sherry on Sundays; where Mills provided massage for the weary. Here were the Snipers, resting perhaps from a long day immobile in a forward “hide”, as they searched the hills with their telescopes or binoculars. Here were the Provost positions, their Bren gun covering the road up to Choksong. Here were Corporal Watkins, Stockley, and the cook-house helpers ready to make the next meal on their improvised ranges. Here was a tent, some said luxuriously appointed within, marked “RSM”, from which might now emerge the robust figure of the Physical Training Instructor—aptly named Strong—who shared it with the owner. Forward, the Drums were dug in on either side of the road. Here, by the ford, was a sign that said “56-MAIN”. This was the centre around which the 1st Battalion, The Gloucestershire Regiment, lived and fought in the area of Choksong.

But this was not all. Forward here, with the fighting element of the Battalion, was Frank’s heavy mortar troop. That “independent” mortar troop! Surely, even the egregious Support Company could hardly surpass that seasoned, well-knit body of old sweats: yet not so old that they could not nip nimbly enough to the long 4.2 inch mortars that they fired so ably.

And forward, too, Guy’s gunner Observation Post parties: young Bruce with A Company; Ronnie with D Company; and imminently joining Denis’s Company Headquarters, Recce.

Four miles behind this line, Rear Headquarters harboured the administrative vehicles, turned back the unwanted from the rear, welcomed those weary ones who needed relief from the eternal night watches. Behind them were John, and Colour-Serjeant Fletcher, forever promising to bring socks up to the Regimental Sergeant-Major. And back in Uijong-bu were Freddie and ‘B’ Echelon, indenting, submitting, requesting, inviting, demanding, stealing the many things we needed daily.

Somewhere between—and a little to the east—were disposed the 25-pounder pieces of the 45th Field Regiment, including our own 70th Field Battery—Guy’s Battery. Like the eyes that watched ceaselessly from A and D, B and C, in their Observation Posts, in their night Listening Posts along the river, on the peaks of the hills and in the valleys; like the ears that listened beneath the wireless and telephone head-sets along the signal nets; like the hands that waited by the mortars and machine-guns, by the surgical instruments and the dressings, the gunners were waiting.

All of us were waiting.

We waited until the 22nd of April, 1951. On that day the battle began.

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

22nd April, 1951

SHAW drove me back from Brigade Headquarters where I had been to see Boris. It was a fine mild afternoon as the jeep drove north along the road which wound among the hills. As we passed Rear Battalion Headquarters, I saw the Assistant Adjutant, Donald, and we waved to one another. I would have liked to stop but I had been away for almost three hours and it was high time I was back.

The earth and the wind smelt of April; the hillsides, as yet bearing the winter skeletons of shrub and dwarf oak, were plainly alive with new life. We reached the top of the ascent below Kamak-San, and Shaw put her into top gear as we ran on down the light slope through the gorges that led to our destination. I lit a pipe and we chatted until, rounding the last long corner, we came to the ford and the little temporary village of vehicles and holes in the ground which we called “home”.

Shaw went off to do some maintenance and I walked over to the Command Vehicle. Richard, the Signal Officer, met me on the steps:

I said: “Where’s Henry?”

“He’s gone off with the Colonel.”

“Where?”

“They’re all down at the river. There’s some sort of flap on. I thought you’d heard,” said Richard.

Well, I hadn’t heard, but I got the scout car and made off down the road towards Choksong. On the way, Yates, the driver, told me that, only an hour or two since, OPs had spotted enemy movement making south towards Gloster Crossing. It was no great push as yet: only very small parties, and very few of these—probably reconnaissance patrols. But how very odd that, after concealing their hand for so long, they should alert us by sending down daylight patrols that couldn’t keep themselves concealed. Was it a deliberate blunder, only a deception; or was it the real thing done by parties of rather badly trained soldiers? I thought all this over as we passed through Choksong and bumped on northwards towards the little cutting through the last low hill that barred our way to Gloster Crossing.

At the cutting, we stopped. Yates concealed the scout car in one of the many open dugouts and I made my way forward on foot. The road ran round a small bend and there, quite suddenly, one was out in the open, in full view of any enemy across the river.

Between the cutting and the river, it was flat rice paddy; flat to the edge of the river which had worn down the soil through the centuries until, now, the bed was twenty, thirty—in some places forty feet—below the top of its banks. On the very edge of the south bank lay a ruined village: a tumbled, charred wreck of a village, whose dwellings, however humble by Western standards, had nonetheless been home to their poor occupants before war had drawn two armies back and forth across the land. Among the crazy roofs, the tottering walls that remained, the 1st ROK Division had dug a network of open trenches during the defence of the river at Christmas time, 1950.

Across the rice paddy, the road ran upon a low embankment, crossed a slightly higher bund at right angles, to enter the village and form a crossroads, only to desert the houses once more as it plunged down steeply through a cutting to the very water’s edge.

Originally, perhaps for generations, the road had been but a poor cart track, hardly capable of carrying tracked, much less wheeled, vehicles in wet weather. But the Sappers had widened and strengthened it, had laid steel-mesh matting upon a re-graded surface in the cutting and, by now, had set a series of marker buoys showing the course of the underwater bridge; a ford which the Koreans had built and used long before the Japanese had established their rule throughout the land.

This was Gloster Crossing.

Along the bund to the right of the road, a small group of figures were lying on their stomachs observing the opposite bank. After a second glance, I picked out the Colonel and Henry, the Intelligence Officer, and went over to them.

“What’s up, Henry?”

He wriggled his way up to the edge of the bund.

“Over there,” he said, pointing. “That’s the fourth group we’ve seen—just a few men. The Colonel has got the mortars on to them.”

A moment or so later there was a series of tiny flashes on the edge of the hill, over the river; a series of puffs of black smoke that disappeared swiftly in the light wind.

“That ought to tickle them a bit,” said Henry.

The Colonel put his glasses down and began to look at his map. I joined him.

“This looks like the real thing,” he said. “It may only be a feint— we’ve had all these other reports about patrol action to the east; but I don’t think that it is. We’ll have a fifty per cent stand-to, to-night. I think C Company had better put an ambush party on Gloster Crossing—a strong fighting patrol. They’d better come down immediately after last light. I’ll brief the patrol commander myself.”

I went back to the scout car and we drove back to Battalion Headquarters, where I wrote the signal about the scale of sentries and alertness, and telephoned Paul, to warn him about the ambush party. Paul said it would come from Guido’s platoon; and that he and Guido would be down for the briefing.

The light was fading as Henry came up the steps into the Command Vehicle and said: “The party on Gloster Crossing is in position.”

“Just let everyone know, Henry,” said the Colonel.

In front of my built-in desk was the one-inch map on which were marked our positions: chinagraph symbols that formed a comprehensible if uneven pattern; symbols that translated the business of defending the approach along this country road to Seoul, the capital, from the personal to the impersonal. Yet here, in an infantry battalion headquarters, in the quiet that only the passing of the stream disturbed, we knew what other watchers at higher echelons could not know in the same detail: each hill, each trench, each weapon, and, above all else, each man who would be fighting when the battle was joined.

I looked across at the Colonel. Thick rings of blue-grey smoke rose from his pipe as he sat, one hand upon his crossed knee, lost in thought. Before a battle, there must come a time when every commander reviews his strength, his dispositions, and—his prospects. And, regardless of his past successes, each ensuing combat must raise for most at least a momentary doubt, a second’s fear, as to its outcome. Now, too, demands for secrecy of sentry posts, of trip flares, and of all alarum measures, must prevent, at least by night, a general tour of the force and thus withhold from its commander the special moral strength imparted by the troops’ stout hearts.

As minutes passed, as hours grew upon the clock, I thought most often of those watching eyes along each section, each platoon, each company front; of all the eyes that peered into the darkness to our west and to our east, battalion flanked by battalion, Geordies, Belgians, Riflemen, Puerto Ricans, Americans, Turks, ROKs. And down by Gloster Crossing, where the river splashed against the fifty-gallon drums that marked the ford, sixteen men of 7 Platoon were watching especially as the moon rose over the broken walls of the village and lit the black waters.

A voice said, “There’s someone at the Crossing, sir.”

Guido looked across to the north bank and saw that four figures had entered the stream and begun to cross, moving clumsily as the current caught at their knees, their thighs, their waists, as they progressed.

The night wind seemed lifted amongst the old ROK trenches. It seemed as if a sigh stirred the men in ambush before they awoke to complete, absolute alertness; before the shock of certain, impending action was absorbed by their minds and they became accustomed to and at ease with the thought of it.

Now the first crossers were nearer the shore and had been caught up by a further three. Already, the splashing of their cold bodies, pushing across the tide might be heard above the noise of the river hurrying past the buoys and lapping upon the beach. Now their figures were more distinct, their caps and tunics moonlit, their weapons outlined. Soon they would leave the water, already receded to their knees, and step up on to the shore and then ascend the cliff, up through the cutting.

No other sounds yet break the stillness, except the river splashing round the stones, the markers, and the men. No cry of fear, no fleeing feet, no shot in panic disturbs the April midnight quiet. These men are resolute.

No cough, no careless cigarette, no clatter of a weapon clumsily handled alarms the enemy’s approach. These men are trained.

The seven moonlit figures still come on; each second adds another detail to their faces, arms, accoutrements. Another twenty yards, fifteen, now ten, now five,—now——

Now!

The light machine-guns fire! The silence dies abruptly as the guns’ fierce echoes sound east and west along the river between the cliffs; south to the slopes of Castle Hill where eyes and ears, alerted by the flashes, strain for more news. And north, across the river, to whatever force ma...