- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Great Central Railway

About this book

This compelling book centers on the Great Central Railways early history, focusing particularly on its drive to reach London. It follows the subsequent fortunes of the London Extension right up until its closure, and into the preservation era, examining the remarkable achievements of hundreds of enthusiasts and their continuing struggle to fulfill the aspirations of those 1969 visionaries.In 1899 the Great Central Railway opened a new main line between Nottinghamshire and London. It was built to the highest of standards; civil and mechanical engineers able to benefit from the experience of over fifty years of British railway construction. It was a glorious achievement. Yet, despite incorporating some of the best facilities to enable it to operate in a more efficient way than its older rivals, it had a short working life compared to its contemporaries. By the end of the 1960s, most of it had closed. However, ironically, that abandonment by the state-owned British Railways presented an independent and enterprising group of railway enthusiasts with a unique opportunity to operate their own main line with their own engines. In 1969 the Main Line Preservation Group was formed with a vision to re-create a fully functioning, double track, steam-worked main line between Nottingham and Leicester. This book explores the journey, development and changes of the Great Central Railway and is a fantastic guide to how the railway industry has changed over time.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Preservation

Early Days 1969 – 1976

After the Nottingham–Rugby passenger service was discontinued, the only sections of the Great Central Railway’s London Extension that remained attached to the national rail network were between London Marylebone and Harrow-on-the-Hill, used as part of an outer suburban service to Aylesbury, and from Nottingham (Weekday Cross Junction) to the outskirts of Loughborough, to retain rail connections to the Ministry of Defence (MOD) Depot at Ruddington and British Gypsum’s Works near East Leake.

Quorn & Woodhouse Station as it appeared in 1970 in the uncertain time between abandonment by British Rail and take over by the preservationists. Fortunately, it did not suffer the same attention from vandals as Belgrave & Birstall Station closer to Leicester. However, the preservationists could not prevent British Rail removing the down line in the summer of 1976, seen here. (Kidderminster Railway Museum)

The fact the last trains ran in 1969 was not significant for British Railways; it was merely the conclusion of a process. For the railway preservation movement, however, the timing was important because it coincided with a period of heighted nostalgia for railways following the implementation of the Beeching Plan of 1963 and the ending of steam traction on Britain’s railways in 1968. Those two events had given impetus to a trend that had been growing steadily from the mid-1950s. Since then, volunteers had proved it was not only possible to preserve steam locomotives, but also to run narrow-gauge passenger trains such as those in Wales (Talyllyn Railway in 1951 and Ffestiniog Railway in 1955), and operate standard-gauge, single-track branch lines such as the Bluebell Railway (1960) and the Keighley & Worth Valley Railway (1968). It was only logical, therefore, that the next step should be the acquisition of a double-track main line on which preserved steam locomotives hauling express passenger trains could be run. As soon as the closure of the Great Central Railway’s London Extension was announced, it became the obvious candidate, and even before British Railway’s last passenger services stopped running, enthusiasts were discussing how they might take over the route.

In January 1969 the Main Line Preservation Group was created, with the aim of acquiring from British Railways the line from Leicester to Nottingham. They earnestly wanted to save everything that remained in situ – buildings, track, signalling, telegraph poles, etc – so they could take over a fully-functional railway. As they had no legal powers, however, they were unable to prevent the removal of equipment. The most notable losses were the signals and signal boxes. (The only signal box that eventually passed into the preservationists’ hands in situ was at Loughborough, and then that was only as a shell, all the electrical equipment and the lever frame having been removed.) This was a crucial period for the Group if it were to prevent further asset stripping.

A detail from the Railway Clearing House map of Britain’s rail network just before the Grouping of 1923. (Author’s collection)

As discussions and negotiations progressed, the Group’s aspirations were refined. The target became the line between Ruddington, just south of the River Trent four miles out of Nottingham, and Abbey Lane Sidings, just north of Leicester Central Station. Then in the spring of 1970 the Group asked British Railways to sell it the line from Loughborough Central Station to Abbey Lane Sidings, although it was still keen to acquire the northern section if sufficient money could be found. At the end of 1971 a charitable trust – the Main Line Steam Trust Ltd – was set up to improve fundraising, by which time the preservationists’ focus was on an even shorter section of the line between Loughborough and Thurcaston Road, just south of Belgrave & Birstall Station on the outskirts of Leicester. Unfortunately, as the track was of value to British Railways, it was still being recovered, and the new Trust had little option, but to curtail its ambitions further if it was to stand a chance of acquiring anything on which it could run trains. By the end of 1972 a purchase price of £383,861 (the equivalent of over £4m in 2012) was agreed for both land and permanent way, the latter being double-track between Loughborough and Quorn & Woodhouse Station, with single-track from there to Belgrave & Birstall Station. In order to keep all this in place, the Trust agreed to pay monthly interest payments of £1,100. In December 1972 Loughborough Station was leased, enthusiasts moving in to undertake basic maintenance, and oversee the delivery of locomotives and rolling stock.

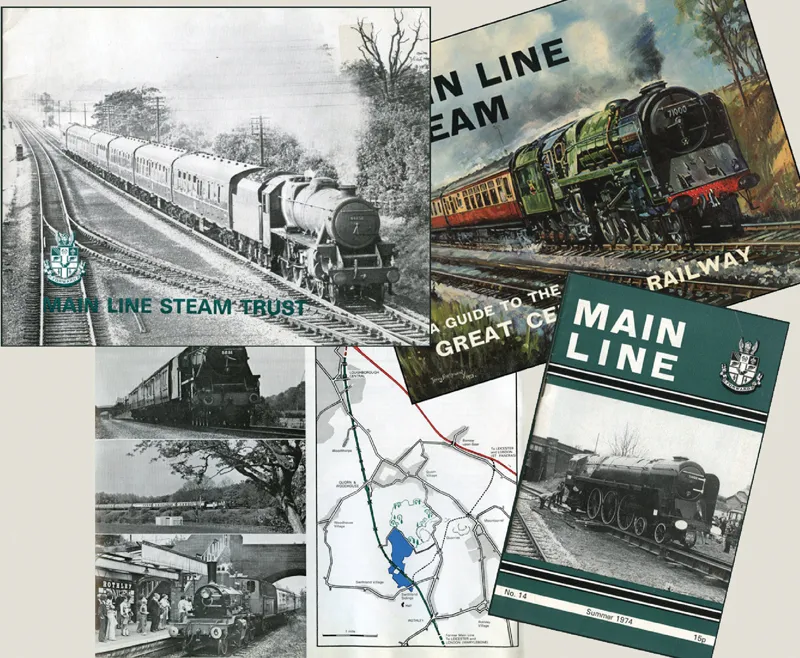

Some of the Main Line Steam Trust’s publicity material of the early 1970s. (Author’s collection)

Inevitably, monthly interest payments could not satisfy British Rail indefinitely, and, at the very end of 1975, it announced that unless outright purchase could be concluded by the end of the financial year (ie March 1976), all track and ballast would be recovered. Selling shares in the project seemed the only way to raise the outstanding amount and to facilitate this the Great Central Railway (1976) plc was created. This prompt action and a share issue promised for May 1976 persuaded British Rail to extend its deadline, but despite this, the financial target could still not be reached, and by July only a single line between Loughborough and Quorn & Woodhouse could be purchased. British Rail moved in promptly and during that summer lifted the former down line between those two stations along with the entire remaining track southwards from Rothley to Belgrave & Birstall. Chastened by this action, the Great Central Railway (1976) plc negotiated a large bank loan so that in early 1977 it was able to buy the section from Quorn to Rothley.

That left enthusiasts with just over five miles of single-track between Loughborough and Rothley, and a future of seemingly perpetual bank repayments. For many in 1977, economic realities had abruptly woken them from their dream of a preserved double-track main line.

Creation of a Branch Line 1977 – 1990

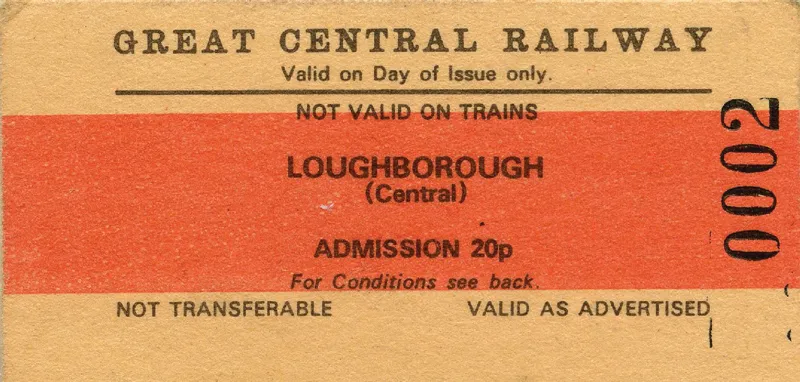

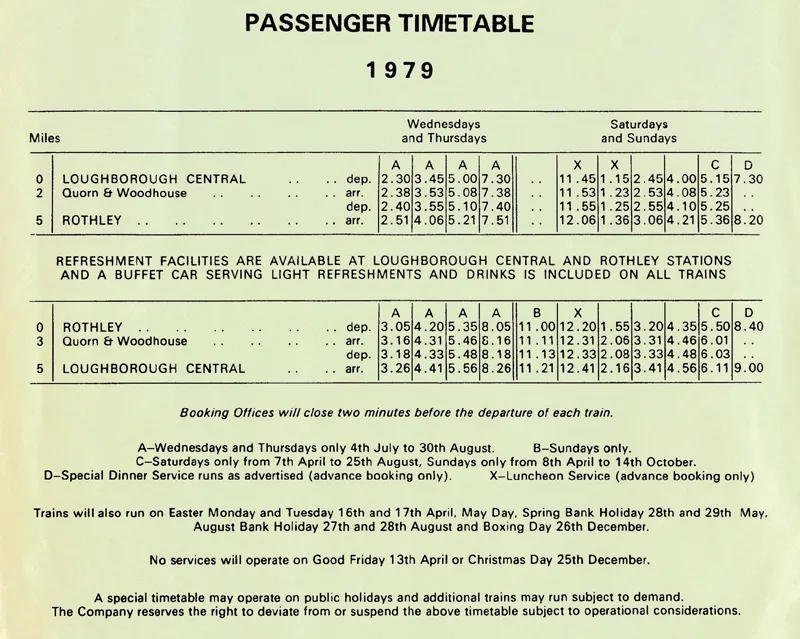

The first enthusiast-owned steam-hauled trains on which the public could travel had started to ply between Loughborough Central and Quorn & Woodhouse from 30 September 1973. Three years later services were extended to Rothley Station, and in 1978 the coveted Light Railway Order was granted by the Department of the Environment, ending the requirement that British Rail staff had to supervise all train movements. From then on, trained volunteers and staff employed by Great Central Railway (1976) plc ran the trains.

For the next twelve years, the railway’s priority was keeping those trains running. In 1973 work had started on erecting a shed at the north end of Loughborough Station in which the restoration and the servicing of locomotives could take place. During the 1980s there were some notable achievements by the railway’s own volunteers and by those working for individual locomotive societies.

In 1986 a national milestone in locomotive restoration, a project once deemed foolhardy, was reached when British Railways 4-6-2 No 71000 Duke of Gloucester was steamed. At the end of the 1960s, its original three cylinders had been removed for display at the Science Museum, London, so new ones had to be cast and machined, and other vital parts of the valve gear forged and fitted, something thought beyond the resources of ‘amateurs’.

During the same period, steady progress was made on restoring passenger carriages and maintaining them in running order. In 1981, Railway Vehicle Preservations Ltd (RVP), which had started in 1968 as the Lea Valley Railway Carriage & Wagon Group, moved to Loughborough, bringing with it its existing collection of historic rolling stock. As well as restoration work, it looked after those already in traffic on the line.

The 1980s were both challenging and exciting times for everyone involved with the preserved railway, its locomotives, carriages and infrastructure. It was a decade when enthusiastic volunteers mastered all manner of skills once thought the preserve of professional railwaymen (many of whom, of course, were volunteers themselves).

1979 publicity. (Author’s collection)

1979 timetable. (Author’s collection)

In 1975 4-4-0 Butler Henderson, built in 1919 as the first of its class, and preserved as part of the National Collection, was moved from Clapham Transport Museum to the Main Line Steam Trust. After a period on static display, the engine was put back into working order at Loughborough and steamed in March 1982. Seen here running into Rothley station, it remained on the railway until the spring of 1992 when it was moved to the National Railway Museum in York. (Author)

It...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Genesis

- To London

- To Closure

- Preservation

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Great Central Railway by Michael A. Vanns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.