- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Seaforth World Naval Review 2017

About this book

"This fascinating book examines trends in maritime strategy and geopolitics . . . including technological advances and significant new ships."—Nautilus Telegraph

This annual has an established reputation as an authoritative but affordable summary of all that has happened in the naval world in the previous twelve months. It combines regional surveys with one-off major articles on noteworthy new ships and other important developments. Besides the latest warship projects, it also looks at wider issues of importance to navies, such as aviation and electronics, and calls on expertise from around the globe to give a balanced picture of what is going on and to interpret its significance.

Features of this edition include an in-depth analysis of the Royal Netherlands Navy, while Significant Ships will cover the USN's radical new Zumwalt class destroyers, the Republic of Korea's amphibious assault ship Dokdo, and the JMSDF's Akizuki class destroyers, among others. There are also technological reviews dealing with naval aviation by David Hobbs (with a focus on the present state of the RN's Fleet Air Arm), while Norman Friedman surveys naval surface-to-surface missiles.

The World Naval Review is intended to make interesting reading as well as providing authoritative reference, so there is a strong visual emphasis, including specially commissioned drawings and the most up-to-date photographs and artists' impressions. For anyone with an interest in contemporary naval affairs, whether an enthusiast or a defense professional, this annual has become required reading.

"An extraordinarily useful annual from the point of view of a comprehensive update on the world's navies . . . a key resource for keeping up, whether in cabin or armchair."— Seaweed

This annual has an established reputation as an authoritative but affordable summary of all that has happened in the naval world in the previous twelve months. It combines regional surveys with one-off major articles on noteworthy new ships and other important developments. Besides the latest warship projects, it also looks at wider issues of importance to navies, such as aviation and electronics, and calls on expertise from around the globe to give a balanced picture of what is going on and to interpret its significance.

Features of this edition include an in-depth analysis of the Royal Netherlands Navy, while Significant Ships will cover the USN's radical new Zumwalt class destroyers, the Republic of Korea's amphibious assault ship Dokdo, and the JMSDF's Akizuki class destroyers, among others. There are also technological reviews dealing with naval aviation by David Hobbs (with a focus on the present state of the RN's Fleet Air Arm), while Norman Friedman surveys naval surface-to-surface missiles.

The World Naval Review is intended to make interesting reading as well as providing authoritative reference, so there is a strong visual emphasis, including specially commissioned drawings and the most up-to-date photographs and artists' impressions. For anyone with an interest in contemporary naval affairs, whether an enthusiast or a defense professional, this annual has become required reading.

"An extraordinarily useful annual from the point of view of a comprehensive update on the world's navies . . . a key resource for keeping up, whether in cabin or armchair."— Seaweed

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 OVERVIEW

INTRODUCTION

‘Against danger, it is best to be prepared’ wrote the Ancient Greek storyteller Aesop in his fable of The Wild Boar and the Fox. The moral of the story seems particularly relevant at the present time as risks from both state-related tensions and nonstate-related violence continue to dominate the newspaper headlines. Indeed, there have been some indications over the past twelve months that governments worldwide are taking heed of the danger. Notably, defence reviews in countries as far apart as Australia and the United Kingdom have committed to bolstering spending to fund both refreshed and new capabilities.1

An examination of the outcomes of the Australian and British defence reviews is instructive in terms of both their similarities and their differences. Interestingly, both commit to spending in the order of two per cent of national wealth – as measured by gross domestic product (GDP) – on national security. However, the Australian figure represents fulfilment of a previous pledge to increase spending that has already risen by some thirty per cent over the last decade, whilst the United Kingdom’s commitment provides a floor to a long period of steady decline. Both reviews also make particular reference to the need to support an international rules-based order and the dangers posed by terrorism, as well as the rapidly expanding importance of cyber security. Expanding investment in these capabilities is a clear priority in the British review but the Australian white paper is more nuanced. With one eye to China’s expansionist policies, much of Australia’s planned defence investment programme is meant to facilitate conventional operations against a state opponent, primarily in the Indo-Pacific region.2 One consequence of this is that the Australian review places much greater emphasis on expanding ‘hard’ power naval capabilities.

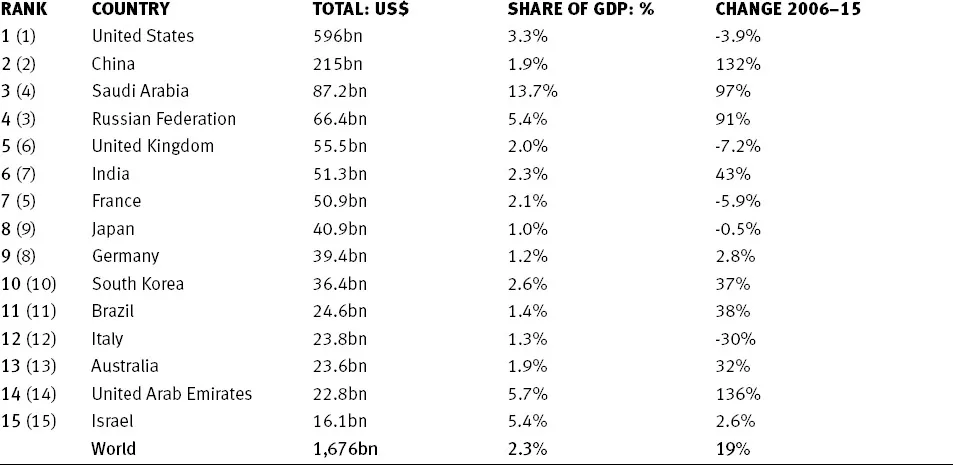

Table 1.0.1: COUNTRIES WITH HIGH NATIONAL DEFENCE EXPENDITURES – 2015

Information from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) – https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex/ The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database contains data on 172 countries over the period 1988-2015.

Notes:

1 Spending figures are at current prices and market exchange rates.

2 Figures for China and the UAE are estimates, with the UAE figure relating to 2014. Previous figures for China have been reduced downward from previous figures contained in the SIPRI database.

3 Data on military expenditure as a share of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) relates to GDP estimates from the IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2015.

4 Change is real terms change, i.e. adjusted for local inflation.

5 Figures in brackets reflect rank in 2014, revised for latest information.

The trend towards increasing defence spending is also reflected in Table 1.0.1, which is based on the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s (SIPRI’s) annual review of world military spending.3 Estimated global defence spending grew slightly to US$1,676bn in 2015: the first time since 2011 thar there has been a real-terms increase. Unsurprisingly, expenditure in the regional hotspots of Eastern Europe, Asia and – to the extent there was data available – the Middle East showed the greatest growth. However, there were also signs that recent declines in North America and Western Europe are coming to an end as the security environment becomes more complex. What the future holds is more difficult to discern. The share of national wealth expended on the military has arguably reached unsustainably high levels in a number of countries. This is particularly so for those, such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, that have economies heavily exposed to the decline in world oil prices. As a result, both countries – currently third and fourth in the list of big spenders – are expected to see reduced defence budgets in 2016.

Given, particularly, Russia’s difficult situation, it is easy to conclude that the recent willingness exhibited by many Western European countries to spend more on their militaries in response to Russian adventurism in Ukraine and elsewhere will soon be reversed as risk perceptions are adjusted downwards. Certainly, Russia’s navy continues to pay a heavy price for its intervention in the Crimea and the Donbass, most notably through the impact of sanctions on its modernisation plans. Its French-built Mistral class amphibious assault ships now fly the Egyptian flag, whilst progress on important surface programmes continue to be slowed by lack of components.4 In spite of this backdrop, it appears that many countries have undertaken a fundamental re-appraisal of the risks they face – perhaps for the first time since the end of the Cold War – and have become concerned by the result. There appears to be a broad consensus that higher levels of spending will be sustained for the rest of the decade.

One further element of uncertainty, however, arises from the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union that was announced on 24 June 2016, just before this annual’s cut-off date. The consequences will not be felt only within the United Kingdom, including a likely revisiting of the relationship between Scotland and the rest of the Kingdom, but also more widely throughout Europe. In the words of The New York Times, ‘For the European Union, the result is a disaster, raising questions about the direction, cohesion and future of a block built on liberal values and shared sovereignty that represents, with NATO, a vital component of Europe’s post-war structure.’5 It seems inevitable that the decision will have large implications for both British and European security structures but it is too early to make a meaningful assessment of what these might be.

-plgo-compressed.webp)

The Royal Australian Navy’s Collins class submarine Rankin pictured operating with one of the navy’s new MH-60R Seahawk helicopters in March 2016. Australia is one of a number of countries bolstering defence spending against a more threatening international background. Its 2016 Defence White Paper confirmed plans to double the country’s submarine flotilla as the existing boats are replaced, with a conventional derivative of DCNS’ ‘Barracuda’ design being subsequently selected for the contract. (Royal Australian Navy)

FLEET REVIEWS

Given protracted implementation times for major defence programmes, recent decisions to bolster defence spending in many Western countries inevitably have negligible impact on the estimated strengths of the world’s major navies outlined in Table 1.0.2. For example, work on Australia’s Project SEA 1000 – the replacement of the existing Collins class submarines with a greatly enlarged force – commenced in 2007.6 However, the recent white paper confirmed that it will not be until the early 2030s that the first boats begin entering service. That being said, the changing security environment will inevitably have a somewhat more immediate major impact on the ‘direction of travel’ on a number of fleets. This is particularly the case for many of the medium-sized European navies, which underwent a major transformation from an anti-submarine and littoral defence configuration at the end of the Cold War to a new emphasis on expeditionary stabilisation operations.7 Having now largely completed this painful reconstruction, they face an at least partial renewal of the original Cold War threat.

Two of the European fleets that are ‘victims’ of this somewhat ironic turn of events are the Royal Danish Navy and the Royal Netherlands Navy, analysed in this issue by first-time World Naval Review contributors Søren Nørby and Theodore Hughes-Riley. Both countries are historic maritime powers that retain significant economic interests in the safety and security of global maritime trade. Both have also proved willing to take an active, international role in countering the instability that followed the end of the Cold War’s essentially bipolar world order. This is reflected in the acquisition of some powerful, flexible warships that provide valuable capabilities to the NATO alliance. However, financial considerations mean that their navies are now much smaller than they once were. It is by no means certain that there is enough money even to retain existing capabilities.

Whilst European events will always be a core interest to a British-based publication such as World Naval Review, it is important to note that it is tension in Asia that remains the most important influence on world naval developments. Much current focus is on the imminent outcome of the Philippines-initiated arbitration case against China’s ‘nine-dash line’ claim in the South China Sea at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, a hearing in which China has refused to participate. Both parties have been attempting to build diplomatic support for their position. A joint communique issued by the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) after a meeting with China’s foreign minister Wang Yi on 14 June 2016 emphasising, inter alia, ‘… the importance of non-militarisation and self-restraint in the conduct of all activities, including land reclamation, which may have the potential to undermine peace, security and stability in the South China Sea …’ was therefore something of a setback for China’s diplomatic offensive given its current island-building strategy. Equally, the statement’s swift retraction provides a strong indication of China’s ability to put pressure on some ASEAN members to prevent emergence of a unified opposition.8 This tension between fear of China’s expansionary inclinations and acknowledgement of the realities of its economic influence is evident in Mrityunjoy Mazumdar’s review of the Royal Malaysian Navy. As must surely be the case for other countries in the region, he concludes that Malaysia will face difficult choices in charting a way forward in the face of China’s ‘divide and rule’ tactics.

-plgo-compressed.webp)

The changing global environment has meant that fleets that have reconfigured towards low-intensity stabilisation and peacekeeping activities may find themselves short of war-fighting assets. The Royal Netherlands Navy is one of a number of European fleets that find themselves in this position, albeit ships like the new JSS Joint Support Ship Karel Doorman pictured here appear sufficiently flexible to be useful in a range of scenarios. (Royal Netherlands Navy)

Table 1.0.2: MAJOR FLEET STRENGTHS MID 2016

Notes:

1 Figures for Russia and China are approximate.

-plgo-compressed.webp)

International relations in Asia continue to remain strained, partly because of China’s assertive stance towards its maritime claims in the South China Sea and elsewhere. This is leading to growing co-operation between other nations that see their own interests threatened, albeit China’s economic influence mean that some are unwilling to take an overtly confrontational stance. This image shows the Indian Project 17 frigate Shakti operating with other warships in the Philippine Sea in June 2016 during the latest Malabar training exercise with Japan and the United States. Japan was invited to become a permanent participant in the Malabar series i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Section 1: Overview

- Section 2: World Fleet Reviews

- Section 3: Significant Ships

- Section 4: Technological Reviews

- Contributors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Seaforth World Naval Review 2017 by Conrad Waters in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & History Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.