![]()

Chapter 1

The Roman Army of the Principate

The legions

To understand the changes that affected the organization of the Roman military forces during the third century AD, it is necessary to present a complete, albeit brief, description of the Roman Army during the centuries of the Principate.1 Augustus, after the terrible clashes of the civil wars, completely reorganized the Roman military forces and gradually adapted them to the needs of the new political power (represented by him and the following emperors). The core of the army was the legions, composed of professional soldiers: until the Late Republican period, they had been formed of citizens serving in the army according to their economic position, but the civil wars had gradually ended this traditional system of recruitment. The long campaigns of conquest conducted in every corner of the Mediterranean world, and the cruel internecine conflicts, proved to be unsustainable for the traditional Roman society from a military point of view. Until the Second Punic War, the Roman legionaries were all owners of small/moderate farms, who fought for the Roman state in exchange for political representation and defence of their interests. Military activity, however, could not last too long during the year because each soldier was first of all a farmer. Serving in the army was considered to be a great honour, but also only a part-time activity: when the Roman expansionist campaigns started to go past the borders of Italy, these small/ moderate landowners found increasing difficulties in serving the state as soldiers. As a result, especially with the military reforms of Gaius Marius, service in the army was gradually also opened to those members of society who had no property and thus no political representation. These men, known as capite censi, soon understood that military service was their only opportunity to change their social position; as a result, they progressively became a class of professional fighters, whose only occupation was war. By the time of Julius Caesar, the Roman Army was almost entirely composed of professional soldiers: these were extremely loyal to their generals, more than to the Roman Republic. Their survival depended upon the decisions of their commander, from whom they received their pay as well as land and property at the end of their career. This situation gradually led to the birth of many ‘private’ armies, each linked to its commanding general: the two Triumvirates and the civil wars of those years are the perfect representation of this period. Something similar would happen, as we shall see, with the collapse of the central state during the last decades of the Empire. Augustus, after his ascendancy to power, had to change all this and cancel the ‘private’ dimension of Roman military forces. The legionaries remained professional soldiers, but started to be paid by the central state: the farms given to the veterans were also provided by the imperial administration, and thus the loyalty of the soldiers started to shift from their commanders to the ruling dynasty.

The main military unit was the legion: a large heavy infantry formation, entirely composed of volunteers having Roman citizenship. Each legion included about 5,500 men, divided into one elite Cohors Prima and nine ‘line’ cohorts. The First Cohort, formed by the best soldiers of the legion, had 800 men; the other nine cohorts numbered 480 legionaries each. The Cohors Prima had five centuries of 160 men each, while the normal cohorts had six centuries of eighty legionaries each. Each centuria was composed of ten smaller units, formed by seven soldiers plus a single NCO known as decanus and two non-combatants. This kind of unit, known as a contubernium, was the smallest one in the Roman Army. In addition, each legion had its own cavalry component: 120 cavalrymen divided into four turmae, with thirty soldiers each. Each turma was structured on three decuriae, the smallest cavalry unit; this included eight soldiers, a decurio (the equivalent of the infantry centurion) and an optio (acting as NCO). Initially, the major part of the legionaries came from Italy, but as time progressed the provincial elements became increasingly numerous.

The system of ranks of the Roman legion was quite complex but specifically designed to make such a large body of soldiers work effectively. The overall commander of the legion was the Legatus Legionis, or Legate, usually a senator appointed by the emperor; as time progressed, however, many members of the equites social class became commanders of a legion. The aristocrats of the Senate, who had always dominated Roman military organization, were gradually substituted by the members of the middle classes represented by the equites: by the period of the ‘Third Century Crisis’, this process had reached its full development, to the point that Emperor Gallienus officially gave command of the legions only to officers coming from the equites. If a legion was garrisoned in a province where no other legions were located, its commander was also to act as provincial governor; when performing these functions, he was commonly known as Legatus Augusti pro praetore. The second officer in the chain of command was the Tribunus Laticlavius, generally a young member of the Senate with no great military experience, who was assigned to the command of a legion in order to learn from the Legate. The third in command was the Praefectus Castrorum, who was responsible for the building and defence of the legion’s camp; he was a long-serving veteran from the equites social class, who had already completed twenty-five years of service and had served as most senior centurion in a legion. His functions included the training of soldiers and new recruits. The group of senior officers was completed by five lower ranking tribunes known as Tribuni Augusticlavii: these all came from the equestrian class and already had some military experience. They mainly performed administrative functions and commanded two cohorts each.

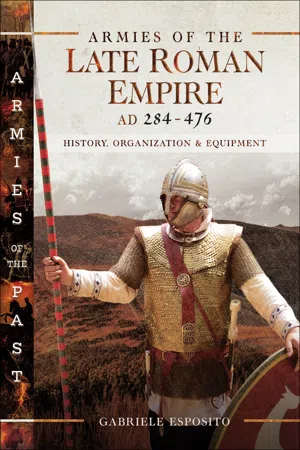

Late Roman officer, with lorica squamata and ‘Berkasovo-I’ helmet. (Photo and copyright by Cohors V Baetica Vexillatio)

The most senior centurion in a legion was called the Primus Pilus and commanded the first century of the elite First Cohort. Once in battle, he had the honour to command the entire Cohors Prima. The other five centurions of the First Cohort were known as Primi Ordines and were considered to be superior in rank to their equivalents of the other cohorts. The centurions commanding the first centuries of the nine ‘line’ cohorts were called Pili Priores and were superior in rank to the Primi Ordines of the First Cohort. Like the Primus Pilus, each of these officers took command of his entire cohort in case of battle. Generally speaking, all centurions came from the lower social classes and became officers only thanks to their personal abilities: these experienced veterans were the true backbone of the Roman Army.

The commander of the four cavalry turmae was known as Tribunus Sexmentris; the decurion commanding each first decuria of horsemen had the honour to lead the entire turma in battle.

The rank organization of the NCOs was particularly articulated, in order to perform a large range of different functions. Each centurion directly appointed his adjutant and second in command, who was called Optio: they performed more or less the same commanding functions as the centurion, but during battle had the important responsibility of remaining at the back of the century in order to keep a close eye on the formation and discourage deserters from abandoning the field. Each Optio had an adjutant known as a Tesserarius, who was third in the century’s chain of command. The Tesserarius was keeper of the watchword and performed several important administrative functions. The system of NCOs was completed by the ten Decani, each of whom commanded one of the contubernia that made up a century. Two auxiliary servants were assigned to each contubernium. Common legionaries could perform a series of special duties, which had a specific designation and corresponded to higher pay.2 The most important of these was that of Aquilifer: the Aquila was the legion’s standard and represented the valour of the whole unit. Losing the standard was the greatest dishonour that a Roman legion could endure. As a result of this symbolic importance, its bearer was chosen among the most experienced veteran soldiers. Each cohort had its own Vexillum that was carried by a special bearer known as a Vexillifer, while each century had its own Signum that was carried by a Signifer; this consisted of a spear shaft decorated with medallions and topped with an open hand to signify loyalty towards the state. In addition to the above, the Cohors Prima had the privilege to carry a special image of the emperor, which was given to an elite bearer known as the Imaginifer. Finally, each century had its own military music, consisting of a Cornicen or Bucinator and a Tubicen. All these transmitted orders by playing their instruments, and usually acted in close combination with the Signifer, who was a rallying point for all the legionaries. The Cornicen played a horn, the Bucinator a particular kind of horn known as a buccina, and the Tubicen a long trumpet.

Late Roman officer, with lorica squamata and sagum. (Photo and copyright by Septimani Seniores)

Late Roman officer, with lorica squamata and pileus pannonicus. (Photo and copyright by Septimani Seniores)

The auxiliaries

As we have seen, the core of the Roman Army were the legions, but these could not perform all the duties required of an army of the time: for example, they lacked light infantry capabilities and had a very limited cavalry component. To fulfill these functions, the Romans used auxiliary units that were formed locally in the various provinces of the Empire. Thanks to this system, the Romans were able ...