![]()

Part I

Revolution: Philadelphia, 1769

On an October day in 1769, a mob descended on the custom house. The day before, an imperial customs official named John Swift, acting on an informant’s tip, seized 5,000 gallons of the colonists’ prized Madeira wine, which smugglers had attempted to land without first paying customs duties. It did not take long for the merchants to suss out the informant’s identity. A mob quickly materialized near Carpenter’s Wharf and caught up with the informant next to the custom house. The informant “was attacked by some Sailors, who were set on him by the merchants. They threw him into the River, dragg’d him out and poured some Buckets of Tar upon his Head, & then Feathered him; they dragged him over the Stones half the length of the Street (the mob still gathering as they went) till they came to the Pillory, the mob pelted him with Stones & mud about four hours, then they brought him to the Custom House.”1 The mob had come calling for John Swift.

Swift had the good sense to flee. But he knew his reprieve would be brief. “I fear it will not end here, for it seems the People have taken into their Heads to mark me out for the next victim of their wrath. I have been guilty of a crime for which I shall never be forgiven—and as I am already condemned, I know not how soon, I may be executed.” On the revolutionary Philadelphia waterfront, “the people”—“the merchants,” “some Sailors,” and other commercial peoples—were judge, jury, and executioner.2

But what, exactly, had been Swift’s “crime”? He had done none other than his sworn duty to enforce imperial revenue laws at the Philadelphia custom house. Why might this have so incited the mob? In fact, Swift’s decision to enforce the law was a marked departure from the usual course of business at the Philadelphia custom house. In the past, Swift and his men had ignored a steady traffic in smuggled goods. But Swift was a conscientious officer nonetheless. He did not have his hand in the till. And unlike those of many of his brother officers, his office was no sinecure. Rather, Swift governed by not taking official notice of smuggling. In this way, Swift kept the peace with the city’s powerful West Indies merchants.3

Swift was well equipped to manage the fragile relations between Philadelphia’s commercial community and the British Empire. He had been born to Londoners of unexceptional stock who moved to the colonies in the early eighteenth century. Swift soon found his calling as a merchant—and a “very successful” one at that. Swift’s new fortunes lent him status, which, in turn, secured him political authority. Swift would serve on the Common Council of Philadelphia from 1757 until 1776. Swift was also active in Philadelphia’s cultural life as manager and treasurer of the “Philadelphia Assemblies,” a dancing society with almost sixty subscribers around 1748.4

Swift understood that governing at the custom house required negotiating authority with Philadelphia’s merchants. Like so many imperial officials who served in the North American colonies, he had learned to what extent commercial peoples in Philadelphia would permit assertions of the empire’s power, and he enforced the law to its limits, but rarely beyond.5 So Swift and other customs officials accepted undervalued manifests in order to reduce duties owed; shipping papers that were forged, altered, or out-of-date; excuses—even outlandish ones—for undocumented trips to foreign ports, and unreported goods on board vessels; late payments—or sometimes none at all—for the many customs bonds required by law. In return, the commercial peoples of Philadelphia made little trouble on the waterfront. They filled out paperwork, took oaths, provided help in small matters, took out customs bonds, and kept their illicit commerce quiet, however common it may have been. At the Philadelphia custom house, then, routine business was “an ongoing series of negotiations, of reciprocal bargaining” between imperial agents and local commercial peoples.6

For several decades, the British Empire had itself benefited from the negotiated authority at the Philadelphia custom house, for reports of calm and quietude testified to the health of the empire. After the Seven Years’ War, however, the British Empire sought to strengthen its coercive hand in the colonies, especially at the custom house. George Grenville’s ministry dispatched new supervisory officers to tighten customs enforcement and punish lackadaisical customs men. The era of negotiated authority at the custom house thus began to unravel as men like John Swift felt intense pressure to enforce the letter of imperial law. The mob was the result. It stalked John Swift until he left office in 1772. “I am told ‘Wo be to the Collector’ is wrote upon the Walls of Houses,” recalled Swift.7

In one of his final letters to the Board of Trade, Swift struggled to take stock of the competing forces—imperial administration and local commerce—that now enveloped the Philadelphia custom house. When the Treasury demanded strict enforcement of the law, it tied Swift’s hands to negotiate his authority with Philadelphians. “What can a governor do without the assistance of the govern’d? What can the magistrate do unless they are supported by their fellow citizens? What can the Kings Officers do if they make themselves obnoxious to the people amongst whom they reside?”8 Without negotiation, Swift lost his legitimacy. The British Empire would not be far behind.

![]()

Chapter One

Custom Houses, Negotiated Authority, and the Bonds of Empire, 1714–1776

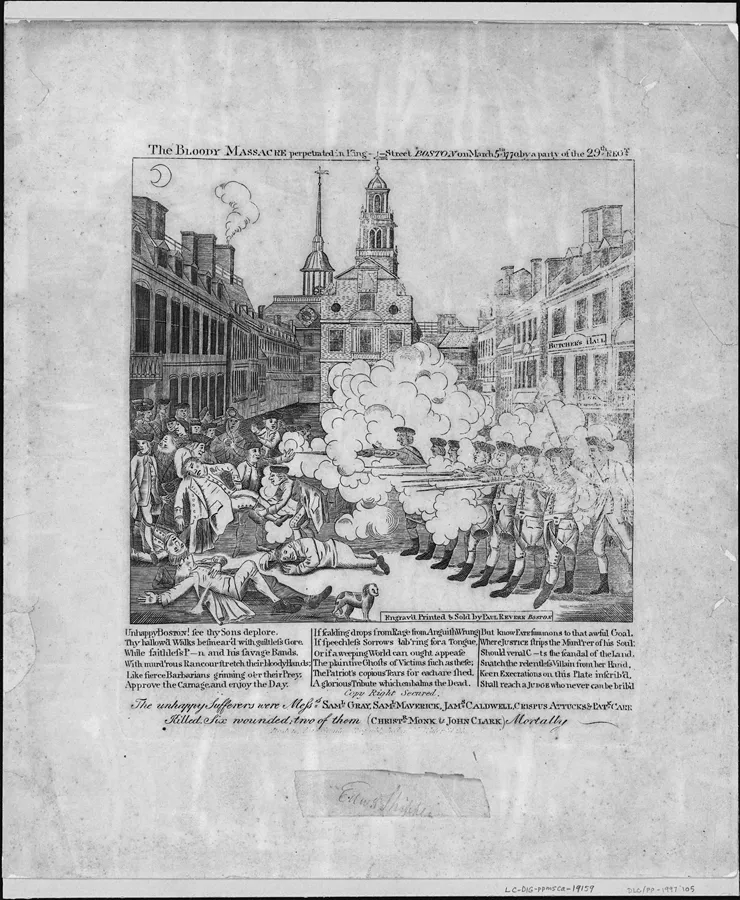

On the evening of March 5, 1770, a scrum broke out between royal soldiers and a “motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and mulattoes, Irish teagues and out landish Jack tars” on King Street in Boston. In the chaos of the moment, one shot was fired, and, quickly afterward, a few more followed. Five colonists were killed. But for Paul Revere, the facts of the Boston Massacre did not speak for themselves. Some needed beautification, especially the protagonists. It would not do for “the American cause to be represented by a huge, half-Native American, half-African American, stave-wielding, street-fighting sailor” like Crispus Attucks. The bad guys also needed a touch-up. Revere arrayed the redcoats in a tidy phalanx and gave each soldier a cold-blooded grimace (fig. 5). He also added two signs to teach distant readers what these murderous soldiers were defending: “Custom House” and, directly above it, “Butcher’s Hall.” Revere had erased Attucks to dignify the mob. He distinguished the custom house to villainize the enemy.1

By the time Revere set to work in 1770, the British imperial custom house had become a backdrop of the gathering revolution. Since 1756, British Treasury officials had been pressuring colonial customs agents to strictly enforce new taxes and commercial regulations. Colonial merchants, sailors, and others fiercely resisted these actions. Their tool of choice was the mob, and from the outbreak of the Seven Years’ War to the first shots of the War of Independence, mobs around the custom house were an all-too-frequent sight on the waterfront.2 Colonists also possessed subtle weapons, such as lawsuits and informal social pressure. “For there was scarce a port in America,” recalled Commissioner of Customs Henry Hulton, “where an Officer had endeavoured to make a Seizure, or refused a complyance with the will of the People that he had not been tarred, & feathered.”3

Tar and feathers represented a new tactic, but colonists’ other methods for resisting customs officers dated back to the seventeenth century.4 Until 1756, however, colonists made only sporadic use of these practices. By and large they did not need them. Prior to the Seven Years’ War, customs officials in the colonies, under unremitting pressure from local men of the market, had consistently bent or broken the letter of the Navigation Acts and measures such as the Sugar Act. This lax administration was a universal feature of custom-house governance in eighteenth-century America until the American Revolution. Nor was it an accident. Imperial officials in London were well aware of the smuggling that flourished in North American ports. They knew of the great deal of slack between the laws and regulations of Parliament, the Treasury, the Board of Trade, and the Foreign Office, on the one hand, and on the colonial waterfront, on the other. Whitehall allowed local norms to determine “what were legitimate and what were illegitimate practices” at the custom houses and other imperial institutions.5

For managers of empire like Robert Walpole, colonial smuggling ironically strengthened the bonds of empire. The colonial merchants who did business at the imperial custom house sought access to lucrative markets—both legal and illicit—in the West Indies and elsewhere. As they pressured customs officials to allow trade in prohibited goods or with prohibited ports, these colonial merchants consistently violated the basic terms of the British Navigation Acts. But in their pursuit of commercial gain at seemingly any cost, they enlarged the influence of the British Empire. And for metropolitan observers, it was increasingly clear that colonial commerce that ran afoul of the Navigation Acts siphoned supplies and capital from the rival Spanish and French empires. As colonial merchants negotiated the boundaries of custom-house authority in North America, and plied their technically prohibited commerce, they served the expansionist ends of the British Empire.6

The American Revolution disrupted the system of custom-house governance that had taken root in the colonies since the Glorious Revolution. Around the time of the Seven Years’ War, rival visions of empire called into question the quiet understanding that had structured legal relations between metropolitan authorities and colonial customs officials on the one hand, and colonial customs officials and colonial merchants on the other. As the colonies became viewed as an untapped source of revenue, Treasury and other officials stepped up their calls for colonial customs officials to tighten enforcement of customs and other laws.7 Parliament also created new forms of oversight and control in the colonies, so customs officials, to say nothing of colonists, more viscerally sensed imperial authority. By 1770, then, when Paul Revere memorialized the Boston Massacre, the custom house had become a universal symbol in the colonies for imperial excess.

The disruption of imperial governance would prove to be brief. By 1789, when the new federal government of the United States began operating its own custom houses, merchants and federal customs officials would again find ways to negotiate the limits and possibilities of the federal government’s authority at the custom houses. The founders would of course look to the meaning of the American Revolution to make sense of the world in which they lived. But in imperial customs law and administration during the American Revolution there was also a more specific cautionary tale about how not to govern an empire.8

The Fiscal-Military Revolution and Its Discontents

Empire had preoccupied English monarchs, and had increasingly defined English political culture, since the unification of England and Scotland in 1603. The “fiscal-military revolution” provided a governmental framework to operate and expand the empire. This revolution “radically” increased taxation, drastically enlarged military capacity, and generated a bustling bureaucratic administration “devoted to organizing the fiscal and military activities of the state.”9 The transformation of the English state was particularly noticeable in the realms of taxation and commercial regulation and especially at the custom houses, where the number of employees rose from 1,313 in 1690 to 2,205 in 1782–83. England, now armed with the power to tax, could guarantee revenue to defray the costs of war and expansion.10

A key step in building the English fiscal-military state was granting the Treasury central control over revenue collection.11 In practice, central control meant a hierarchy of bureaus, at the top of which sat the Treasury Board and its subordinate Board of Customs Commissioners. From their perch in the dazzling Long Room atop the London custom house, the commissioners directly supervised prosaic revenue and regulatory activities at English custom houses.12 Waterfront operations were equally impressive. On busy days, over 800 customs officials swarmed around the London custom house—tidewaiters on board vessels awaiting inspection; inspectors supervising the tidewaiters; watchmen along the quays guarding against unauthorized unlading; hundreds of weighers and gaugers on the wharves handling unloaded commodities; surveyors and landwaiters overseeing activities on the wharves. The customs establishment was also active beyond London. In “outports” such as Bristol, custom houses operated under the supervision of a collector, with up to several dozen subordinate officers. From the Long Room, through London, and along the English coast, this apparatus was “one of the pillars of the mercantilist state.”13

The chief business of these customs officials was to enforce the Navigation Acts of 1660, 1663, and 1673, which taxed imported goods to discriminate against foreign commerce and protect English commerce.14 Procedure at the custom house was fairly routine. Each manifest would account for each and every commodity on board a vessel, save for the ship’s “stores” of victuals. From the manifest, officials calculated duties and demanded payment of what would become the state’s revenue. The manifest and other shipping papers also described the vessel’s port of origin and destination. Through these measures, England would guarantee its mercantilist monopoly on shipping by ensuring that vessels remained on their stated course. If a ship’s crew violated these rules—or myriad subsidiary rules—customs officials were to place into collection bonds that merchants and ship captains had entered into before setting out to sea.15

England’s new customs system notched some remarkable achievements in the century following 1690. First, the custom houses collected hundreds of millions in revenue.16 Likewise, commercial regulations, in tandem with military policy, advanced England’s geopolitical interests. The Treasury routinely directed customs agents to be “faithfull & diligent” about preventing trade with France during periods of conflict with France. The custom house was the center of operations for “procuring and pressing seamen” to fill the ranks of England’s increasingly powerful navy. Customs officials also inspected vessels to ensure that commodities produced for the export market actually went abroad, and conversely, that goods produced for domestic consumption were not illegally exported. By 1763, the enforcement of these policies contributed to England’s dominance in the European struggle for global dominion.17

England’s new and reformed fiscal-military institutions required a commensurately new cultural infrastructure to structure relations between citizen...