![]()

1

WHY WE NEED TO BUILD A NEW AMERICAN ECONOMY

My purpose in this book is to explore the economic choices facing the United States and its relations with the rest of the world at the start of the new administration of President Donald Trump and the new Congress. One reason why Washington has been in gridlock for years is that both parties have pursued a deeply flawed vision for America. The Republicans have called for a smaller government when we need a government that does more and better to address slow economic growth, rising inequality, and dire environmental threats. Democrats have called for a larger government but without clear thinking about priorities, programs, management, and finances for an expanded role.

This book charts a better course for American public policy based on long-term societal objectives around the concept of sustainable development. I outline a strategy of scaled-up investments, both public and private, and the means to finance them. I emphasize throughout that the way to break Washington’s gridlock is to build a new national consensus based on local brainstorming in every part of the country. President Trump and the Congress will remain stymied until they both hear from people across the United States that the time for major change has arrived, with clear goals, policy direction, and financing.

My core contention is that with the right choices, America’s economic future is bright. Indeed, we are the lucky beneficiaries of a revolution in technologies that can raise prosperity, slash poverty, increase leisure time, extend healthy lives, and protect the environment. It sounds good, perhaps too good to be true; but it is true. The pervasive pessimism—that American children today will grow up to worse living standards than their parents—is a real possibility, but not an inevitability.

The most important concept about our economic future is that it is our choice and in our hands, both individually and collectively as citizens.

The reasons for the pessimism are real. The United States is experiencing the lowest growth rates in the postwar era. Economic growth recorded since the 2008 financial crisis has been about half of what was forecast in mid-2009: 1.4 percent annual growth from 2009 to 2015 compared with a projected growth rate of 2.7 percent. Around 81 percent of American households, according to a recent McKinsey study, experienced flat or falling incomes between 2005 and 20141. At the same time, the inequality of income has soared over the past 35 years, adding to the concentration of wealth and income among the top 1 percent of the population. In 1980, the top 1 percent took home 10 percent of household income; in 2015, it was around 22 percent.2

While unemployment has declined, from a peak of 10 percent in October 2009 in the depths of the recent financial crisis to the current low rate of around 5.0 percent, part of that recovery has been achieved because individuals of working age have left the labor force entirely, out of frustration at low-paying jobs or no job opportunities at all. The ratio of overall employment relative to the working age (25–54) population has declined from 81.5 percent in 2000 to 77.2 percent in 2015.

If this were not enough, the headwinds seem set to continue. The antitrade sentiments from both political parties over the 2016 election season, leading both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton to reject a draft trade agreement with Asia, reflects a widespread feeling that America has lost jobs in large numbers to low-wage competition with China and other countries, and that more such job losses are to come. Recent research suggests that such fears, long scoffed at by economists, are based on reality.3 U.S. manufacturing sector jobs have shifted overseas, as well as being lost to automation. U.S. counties on the front lines of competition with Chinese manufacturing have experienced the largest job losses.

Automation has become another source of high anxiety. Here, too, economists have generally scoffed at the public fears that machines will take away our jobs.4 Hasn’t the entire industrial era proved that view wrong? they ask rhetorically. Haven’t new machines and technology always created more jobs than they have cost? These questions are fair, but so too are the worries. The advent of smart machines seems to be shifting income from workers to capital, driving down wages, and contributing to the frustration low-wage workers feel about finding a job with a livable wage. Some workers do seem to be squeezed right out of the labor force, and the share of labor earnings in national income is falling, a sign that decent jobs indeed are being overtaken by the robots.

So, yes, Americans have the right to lots of economic fears: of Wall Street traders who destabilize the economy; of the top 1 percent who corral the lion’s share of economic growth; and of jobs and wages lost to China and the robots. But there are still more reasons to worry.

The federal budget deficit in 2016 was around 2.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP,) but given current trends will rise to around 4 percent of GDP in the coming years. The consequence of chronically high budget deficits is rapidly increasing public debt. The Treasury debt owed to the public here and abroad has soared from 35 percent of U.S. GDP at the end of 2007 to 75 percent at the end of 2015. The Congressional Budget Office warns that under current fiscal policies, the debt is likely to reach around 86 percent of GDP by 2026 and 110 percent of GDP by 2036.5

Debt sustainability is one part of the future we leave to today’s children. Environmental sustainability is, of course, the other. And if there is one endangered elephant in the room, one existential worry to keep us up at night, it is the relentless, punishing, ongoing damage that Americans and the rest of the world are doing to the environment. We can’t rest easy on our economic future, and I would not advise doing so for a moment, until we find a path to climate safety and true sustainability for our water, air, and biodiversity. Most importantly, we need to overhaul the energy system, to shift our reliance from carbon-based energy—coal, oil, and gas—to noncarbon energy sources—wind, solar, hydro, nuclear, and others that do not cause global warming. Fortunately, America is replete with renewable energy resources. But there are many other steps we need to take to achieve environmental sustainability, and I’ll get into those in more detail in the chapters to come.

Finally, add to these challenges our nation’s highly divisive and corrupted politics, and it’s not hard to be gloomy. Some leading economists have even declared the end of two centuries of economic growth. We are, to use their jargon, in a new era of “secular stagnation.” And if growth is at an end, social stability could be jeopardized as well, with the economy turning into a zero-sum struggle wherein the gains for some groups must be the losses for others.

The doyen of the pessimists (and author of a wonderful new book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth), Robert Gordon, says we’ve simply run out of big new inventions to keep the economic engine going.6 Gordon argues that smartphones and the Internet simply don’t measure up to mega-breakthroughs like the steam engine, electricity, TV and radio, the automobile, and aviation—the great technological drivers of two centuries of economic advance.

My argument, to be detailed over the course of this book, is that the pessimists have a point—indeed, several of them—but that overall they are mistaken. We are not at the end of progress, at least not if we get our act together. And we can. Even the political paralysis can end if we can discern more accurately and clearly the right path out of our very real and complicated problems. America has confronted and overcome many horrendously large problems in the past—the Great Depression, Nazism and Stalinism, the political exclusion of African Americans, the poverty and heavy disease burden of the elderly—and can do so again.

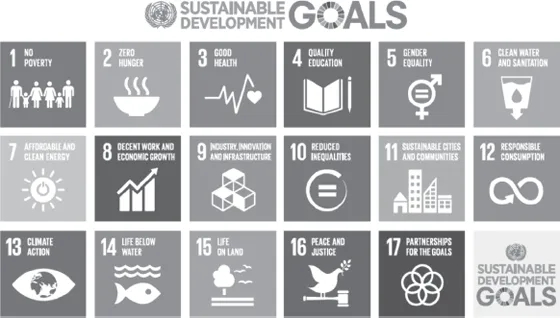

My starting point is a concept, sustainable development, which conveys a new and better approach to national problem solving. Luckily, it’s a concept that’s been around for a while, long enough that we have an extensive body of knowledge and extensive evidence of what to do. And long enough to be acknowledged widely not only by scientists, engineers, and a growing number of investors but also by governments around the world. On September 25, 2015, all 193 governments of the United Nations adopted sustainable development, with seventeen specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as the basis for global cooperation on economic and social development during the coming fifteen years (see figure 1.1).7 On December 12, 2015, the same governments adopted the Paris climate agreement, also built on the concept of sustainable development.8

FIGURE 1.1 The Seventeen Sustainable Development Goals

Sustainable development argues that economic policy works best when it focuses simultaneously on three big issues: first, promoting economic growth and decent jobs; second, promoting social fairness to women, the poor, and minority groups; and third, promoting environmental sustainability. American economic policy has tended in recent years to focus only on the first, economic growth, and not done that very well, in part because it has largely neglected the growing crises of economic inequality and environmental ruin, even as those have worsened dramatically in recent years. Now, because of our multiple policy failures and unbalanced growth, even future economic growth itself is imperiled.

Economic growth, social fairness, and environmental sustainability are mutually supportive, and future growth now depends on addressing the two neglected pillars of sustainable development. Choosing our economic future is the key idea. Economies don’t just grow, achieve fairness, and protect the environment of their own accord. Economic theory and experience make clear that there is no “invisible hand” that produces economic growth, much less sustainable development. Even Adam Smith was clear on that point, and wrote Book V of The Wealth of Nations to emphasize the role of government in infrastructure and education.

But how do we choose? Mainly, we choose our economic future through the decisions we make concerning saving and investment. Societies, like individuals, face the challenge of “delayed gratification”: We achieve future growth by holding back on current consumption and by investing instead in future knowledge, technology, education, skills, health, infrastructure, and environmental protection. And if we invest well, we hit the trifecta, achieving an economy that is smart, fair, and sustainable. Such an economy will create decent jobs, ensure ample leisure, promote public health, and underpin competitiveness in a highly competitive world economy.

Investing well, in turn, will require two things on which America is decidedly out of practice, so much so that even the hint of them will cause many to squirm. The first is planning. We need to plan for our future. I can recall when the very idea of planning became a dirty word, associated with the “central planning” of the defunct Soviet Union. Yet we need planning now more than ever to overcome complex challenges such as overhauling our energy system, an effort that will require decades of concerted action.

The second is the need for more public investment to spur private investment. Ever since Ronald Reagan told us “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem,” we have cut public investment to the bone. We experience it every day with decrepit highways, bridges, levees, and urban water systems; aging airports and seaports; and neglected hazardous waste sites. Yet without government’s role in building infrastructure and guiding the energy transition, private investors—with trillions of dollars under management—will remain stuck on the sidelines, not knowing where to place their bets.

With breakthroughs in smarter machines and information systems, new materials, remote sensing, advanced biotechnology, and much more, there are innumerable ways forward toward sustainable development and higher living standards, including healthier lives and more leisure. But can a complex modern society actually achieve these goals and balance the budget at the same time? I’m going to show why the answer is yes and, even better, look to other countries that are ahead of the United States and are forging the way to the future in meeting certain key challenges such as education, skills training, fairness, and low-carbon energy.

In a recent study, my colleagues and I measured how 149 countries, including the United States, stack up on sustainable development and, notably, on the progress that the countries will need to make to achieve the recently adopted SDGs. The news was eye opening, sobering, but also strangely inspiring. The United States came in twenty-second out of thirty-four high-in...