eBook - ePub

Agent of Change

The Deposition and Manipulation of Ash in the Past

This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Agent of Change

The Deposition and Manipulation of Ash in the Past

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Ash is an important and yet understudied aspect of ritual deposition in the archaeological record of North America. Ash has been found in a wide variety of contexts across many regions and often it is associated with rare or unusual objects or in contexts that suggest its use in the transition or transformation of houses and ritual features. Drawn from across the U.S. and Mesoamerica, the chapters in this volume explore the use, meanings, and cross-cultural patterns present in the use of ash. and highlight the importance of ash in ritual closure, social memory, and cultural transformation.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Agent of Change by Barbara Roth, E. Charles Adams, Barbara Roth, E. Charles Adams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

ASH AS A TRANSFORMATIVE AGENT

CHAPTER 1

Ash Matters

The Ritual Closing of Domestic Structures in the Mimbres Mogollon Region

Barbara J. Roth

The chapters in this volume examine the important role that ash played within prehistoric societies in North America. Many of these studies highlight the use of ash in ritual contexts where its role was for renewal and rebirth, which was an important way to symbolize these processes. Ash was not just used in ritual contexts, however. In looking at different ways that ash was used ethnographically and prehistorically across the U.S. Southwest, it is clear that ash also played an important role in retiring and dedicating domestic structures.

In this chapter I examine the role that ash played in the ritual closure of domestic pithouse and pueblo rooms during the Late Pithouse (AD 550–1000) and Classic Mimbres periods (AD 1000–1130) in the Mimbres region of southwestern New Mexico. This time span encompassed significant social and ideological changes, and yet the continuity in the use of ash described here implies some continuity in domestic ritual practices over time.

Burning and ash were significant components in the ritual retirement of great kivas toward the end of the Late Pithouse period in the Mimbres region. The largest great kivas, found at the largest villages, were ritually retired in very elaborate ways. Extreme burning of Late Pithouse period great kivas has been well-documented by Creel and Anyon (2003; Creel et al. 2015). They argue that the ritual retirement was initially planned from the time of construction. They see the kiva retirements as tied to broader social changes associated with a growing focus on irrigation in the valley and waning ties with Hohokam groups to the west.

The role of ash in kiva retirement is further illustrated by recent work at the Harris site, a Late Pithouse period village located in the central portion of the Mimbres Valley where evidence of the ritual retirement of a Three Circle phase (AD 750–1000) great kiva dating to the AD 800s documents the use of ash and targeted burning (Roth 2015). The structure (Pithouse 55) contained a large adobe-lined hearth filled with clean ash containing an arrow point and a shell bracelet fragment, which was then capped with fifteen centimeters of adobe and several large pieces of ochre (see Ryan, chapter 3, and Adler, chapter 5, for discussions of similar kiva hearth closures in the northern Southwest). The front portion of the kiva was then burned, with the roof falling directly onto the floor near the entryway. Sixteen projectile points were recovered from the burned roof fall, with several recovered from a lens of sand between the roof fall and floor near the entryway. The points have been interpreted as intentionally placed there either as part of the retirement of the structure or as dedicatory objects embedded in the roof when the structure was built. As detailed by Walker and Berryman (chapter 12), projectile points served ethnographically as symbols of power and protection, and their co-occurrence with ash deposits in pueblo kivas in the Jornada region to the east of the Mimbres Valley suggests a shared tradition that may be region-wide versus valley-wide, as discussed in this chapter.

Similarly, a pit filled with smashed ceramic vessels was found in the plaza outside the entryway of this great kiva. The use of this pit has been tied to a feasting event associated with the ritual retirement of the kiva (Roth 2015). A layer of ash was placed on top of the pile of smashed vessels, and two palette fragments were found in the ash layer. The ash is interpreted as representing the final closure of the kiva. Neither of these circumstances is surprising given the ethnographic association of ash with cleansing and renewal; this particular great kiva was replaced by a much larger great kiva after it was retired, and the larger great kiva was retired by burning in the late AD 900s (Creel et al. 2015). Other examples of the use of ash in ritual contexts are known from throughout the Mimbres region and, as documented by Ryan (chapter 3 and Fladd, Hedquist, Adams, and Koyiyumptewa (chapter 4), are similar to the use of ash in closing kivas across the Southwest.

The use of ash as part of domestic rituals has not been studied to the same degree that the use of ash in ritual structures like kivas has been (but see Adams and Fladd 2017). As will be illustrated in this chapter, ash was a component of domestic rituals in the Mimbres region, especially in “closing” houses after they were abandoned. Three examples from across the Mimbres Valley are presented here that highlight the use of ash for domestic closure. The significance of this practice in terms of concepts of cleansing and renewal and its association with other aspects of social behavior are also discussed.

Example 1: Ritually Closing Houses before Building Houses above Them

Several cases of closing a pithouse or pueblo room prior to building another structure above it within the same architectural footprint exist in the Mimbres region. Here I highlight three examples of the use of ash in closing houses using data from my excavations at both pithouse and pueblo sites in the region.

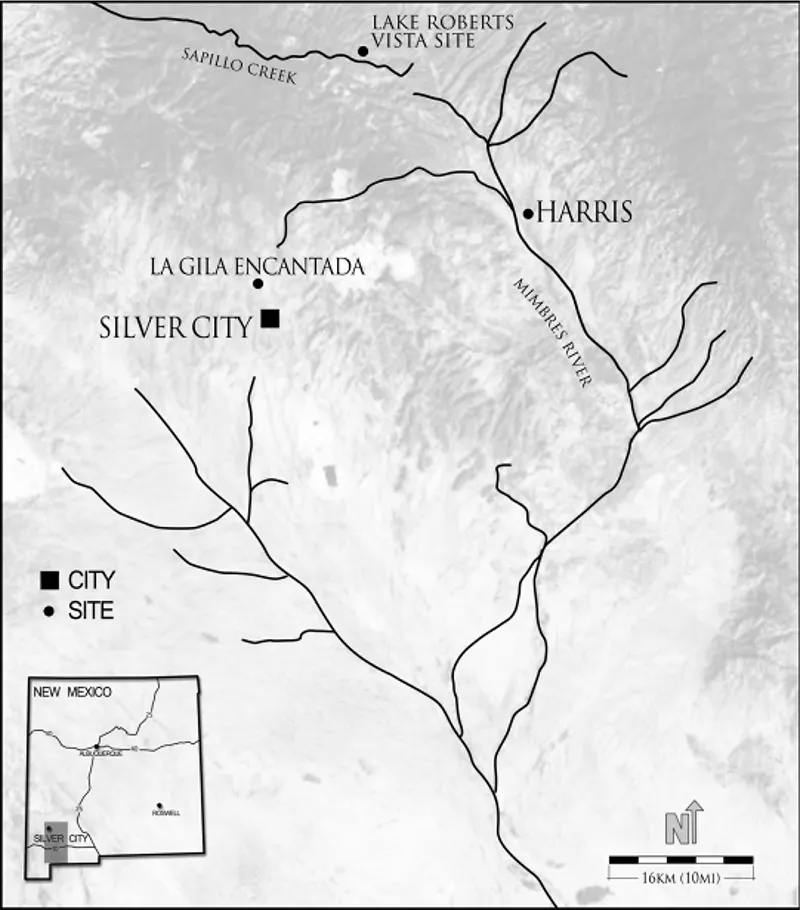

Lake Roberts Vista

The Lake Roberts Vista site (LRV) is located on a knoll above Sapillo Creek, a tributary of the Gila River (figure 1.1). The site contains both pithouse and pueblo components, although the pueblo component has been badly looted, so only limited data are available on it. The site contains a moderate-sized (twenty to twenty-five) pithouse occupation that extends from the knoll top and surrounding terraces above Sapillo Creek. A pueblo component, estimated to be eighteen to twenty rooms, is present on top of the pithouse component on the knoll but does not extend to the slopes below. During both periods, the site had kivas that were apparently used for local community ceremonies.

Portions of six pithouses (one of which was converted into a Classic period kiva) and five pueblo rooms were excavated at the site in the early 1990s, and a large Three Circle great kiva on the west side of the site was tested (Roth 2007; Roth, Romero, and Stokes n.d.). Data from these excavations indicate that the site was occupied from the Georgetown phase (AD 550–650) of the Late Pithouse period through the Classic Mimbres period. Groups appear to have been seasonally mobile during the Georgetown and San Francisco (AD 650–750) phases, with a relatively rapid shift to sedentism observed during the Three Circle phase. Subsistence data and terrace features found in drainages near the site indicate that agriculture was practiced, but it was supplemented with wild resources, including piñon and game. Given the increase in sedentism documented during the Three Circle phase in both architecture and artifact data (Roth 2007) and the fact that many surface depressions mapped at the site likely represent Three Circle phase pithouses suggesting that population increased, it can be reasonably inferred that agricultural production increased through time and increased in importance during the Classic period. The size and depth of the Three Circle phase great kiva is larger than would be expected for a pithouse site the size of LRV, so Stokes and Roth (1999; Roth 2007) have suggested that the kiva was placed on the knoll top to serve a larger community surrounding the LRV site.

Figure 1.1. Lake Roberts Vista, Harris, and Elk Ridge site locations. Created by Russell Watters.

Pithouse 4 contained evidence of three separate occupation surfaces built within the same architectural footprint. The lower floor, which dated to the mid–AD 600s, was cleaned out before abandonment, and it had an ash-filled hearth (a topic to be returned to below). The second surface was directly above the roof fall of the lower floor and was initially interpreted as a “floor” representing a layer of ash with a bear mandible on it (Roth 2007). Another plastered habitation floor was built above this ash layer. Based on the nature of the ash layer, it is now apparent that it was not a floor but instead represented the ritual closure of the lower house prior to building the upper house. Bears are symbols of power in puebloan society, and although bear claws are more commonly represented than other parts of the animal, the purposeful placement of a bear mandible on top of the ash layer indicates that it was part of the closure of the lower floor.

Harris Site

A second case of domestic closure is documented at the Harris site, a large pithouse village located in the central portion of the Mimbres River Valley (figure 1.1). A total of fifty-four pithouses have been excavated at the site, along with a series of sequentially used great kivas (Haury 1936; Roth 2015). Roth (2019a) has discussed community development at the Harris site through the Late Pithouse period. The site was occupied beginning in the Georgetown phase (although an earlier Archaic period occupation may have been present) and continued through the late Three Circle phase. The initial Georgetown phase occupation was small relative to later periods, but the construction of a communal structure indicates that sedentism and perhaps population size was increasing. By the San Francisco phase, evidence for the presence of extended family groups represented by clusters of pithouses with shared traits is present (Roth 2015). Roth and Baustian (2015) see this development as tied directly to land tenure, and argue that these pithouse clusters represent landholding households. Evidence for both extended family groups (pithouse clusters with shared traits) and autonomous households is found during the Three Circle phase. Roth (2019a) argues that two of the extended family pithouse clusters found on opposite sides of the large central plaza were sponsoring rituals based on artifacts found within them. Unlike many other sites in the Mimbres River Valley, no pueblo was built on top of the pithouse village at the Harris site; it appears that groups dispersed from the site in the late AD 900s after the ritual retirement of the largest great kiva, and only a small population of autonomous households remained.

The example of domestic ritual closure at the Harris site involved extensive burning as well as the use of ash, but was similar to the Lake Roberts case in that the house floors were built within the same architectural footprint. At Harris, the lower house (Pithouse 54) was intentionally burned prior to the construction of the second floor (Pithouse 49). One unexcavated burial was found in the floor of Pithouse 54, and it is possible that the house was burned when this individual died. The intentional burning, like the ash deposit at the Lake Roberts site, appears to be related to ritually cleansing the house prior to the construction of Pithouse 49 (see also Adler, chapter 5). This structure has been interpreted as the residence of an important household in the village (Roth 2015), representing an extended family cluster located on the east edge of the large central plaza that the great kivas opened on to (figure 1.2). Pitting on jars found within Pithouse 54 is similar to that found at NAN Ranch and in the Jornada Mogollon region to the west that is consistent with fermentation (Shafer 2003; Miller and Graves 2012). This and the recovery of a palette from another house in the cluster (Pithouse 53) have led Roth (2015) to posit that this household was sponsoring rituals in the associated Three Circle phase great kiva (Pithouse 55). This inference is drawn largely from the fact that smashed serving vessels, which are thought to have held corn beer, and two palette fragments were found in a pit outside the entrance to the kiva that was associated with a feasting event tied to the ritual retirement of that kiva. As noted above, the palettes were found in a layer of ash. Thus, burning and ash appear to have been used in multifaceted ways at Harris to signify closure and renewal, and the burning of Pithouse 54 was likely to have been part of these ritual activities.

Figure 1.2. Harris site map. Created by Russell Watters.

Elk Ridge

A third case of closure is illustrated by another set of superimposed house floors within a pueblo room at the Elk Ridge site, a Classic period pueblo located in the northern portion of the Mimbres Valley (figure 1.1). The Elk Ridge site is the largest Classic Mimbres pueblo in this portion of the valley, with an estimated two hundred pueblo rooms, an underlying pithouse component, and several kivas, including a large unexcavated Late Pithouse period great kiva located in the southern portion of the site. The site sits on both U.S. Forest Service and private land, with a fence line dividing the two. The southern portion of the site, now owned by the Archaeological Conservancy, has been heavily looted, but the portion on Forest Service land is intact due in large part to the fact that it has been buried by alluvium.

Excavations conducted by the author along an arroyo cutting into the western part of the pueblo on Forest Service land has resulted in the excavation of fifteen pueblo rooms (including rooms with multiple floors), a late Three Circle phase pithouse, two extramural areas, a burned ramada, a turkey pen, a midden, six turkey burials, and forty human burials (Roth and Creel 2016, 2017; Roth 2018). The occupation of the pueblo spans the Late Pithouse through the Late Classic periods (late AD 900s to early 1000s). In addition to the Late Pithouse component, two pueblo components have been identified: an adobe pueblo component that apparently dates to the early Classic period and a cobble-adobe pueblo component typical of Classic period occupations across the valley that overlies the adobe pueblo component.

The example of the use of ash in ritually closing a lower house at Elk Ridge involves a structure with three separate floors representing temporally distinct occupations, starting with an early Classic adobe pueblo component (Room 112) and culminating in a cobble-adobe component (Room 105). Interconnected rooms (via doorways) associated with this particular room indicate that it was part of an extended family household. Multiple burials were found in the room floors, and this apparently represents a long-standing household at Elk Ridge. A layer of ash was found between the bottom adobe pueblo component (Room 112) and the second floor (Room 113). The ash layer is inferred to represent the ritual closure of the lowest structure prior to the construction of the second floor, as no evidence of structure burning was found. The previous roof fall was first removed, and then the layer of ash was apparently intentionally placed above the floor of Room 112 before Room 113 was built. A cache of four miniature vessels was found north of this ash layer. Fladd and Barker (2019) have recently documented the use of miniature vessels in the closure of ritual spaces at Homol’ovi in northern Arizona. Interestingly, no layer of ash was found between the second and third floors, but the lack of deposition between them indicates that the upper floor (Room 105) may represent more of a remodeling event that perhaps did not require the same form of ritual renewal.

Other examples of this practice have been documented in the Mimbres Valley, although past excavation strategies in the early 1900s, which often involved removing all fill to the floor, precluded identifying these kinds of depositional events. Despite the difficulties with the data base, it does not appear that a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction: The Deposition and Manipulation of Ash in the Past

- Part I. Ash as a Transformative Agent

- Part II. Ash and Ritual

- Afterword

- Index