![]()

CHAPTER 1

Painting the Gospel Blues

Race, Empathy, and Religion at Pilgrim Baptist Church

“One of the most amazing things that would get me was to look up there and see the Last Supper and see them all sitting there with Jesus—right in front of us. It was like it was so real. It was so real.”1 This description is by William L. C. Bynum, the rector of Pilgrim Baptist Church in Chicago for more than three decades. Church members could fully engage with the biblical figures in William E. Scott’s mural series that adorned the church for more than seventy years because he merged an academic style, learned at such schools as the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and L’Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, with an unconventional racial fluidity not often seen in church interiors in the 1930s, or even much today. Scott’s images of Christ and other biblical figures represent different racial types through skin color, features, and hair texture. In this program, fair-skinned and dark-skinned Christs appear simultaneously as interchangeable figures in the same narrative. Filling most of the apse from floor to ceiling, these paintings held their own in an already lavish interior (figure 1.1). This imagery allowed the members of the congregation to see themselves in the life-size multiracial figures acting out the life of Christ on the walls in front of them.

Austin’s Mission for Pilgrim, 1926–68

Scott’s goals to create images that promoted black pride through a very conventional, representational painting style found great support at Pilgrim Baptist Church in the person of Junius C. Austin (1887–1968), a prominent advocate of social change and African American empowerment. As Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Cornel West wrote in their book The African-American Century, “Before Gardner Taylor, Sandy Ray, Samuel Proctor, J. H. Jackson, and Martin Luther King Jr.—all twentieth-century preachers of enormous influence—there was Junius C. Austin.”2 Before moving to Chicago, Austin had been president of the Pittsburgh chapter of the NAACP. He encouraged southern blacks to move north, and he established the Steele City National Bank and the Home Finder’s League to help blacks once they arrived in Pittsburgh. Austin, raised in a log cabin built by Carter G. Woodson, the great African American historian who created Negro History Week in 1926 in rural Virginia, had a personal and passionate interest in these migrants.3 He began preaching at the age of eleven and earned a BA, BD, and DD from the Virginia Theological Seminary. Austin also became a supporter of Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) because of its community-based programs and focus on making ties with Africa. Austin even gave the keynote address at the UNIA’s Third International Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World on August 1, 1922, in which he declared his allegiance to Garvey and acknowledged what it had cost him, declaring, “We have to teach the world the truth about ourselves and we have to teach the world the truth about God. I am true to this organization. I am one of your earliest friends. I have lost friendship with people within my church for defending Marcus Garvey’s name.”4

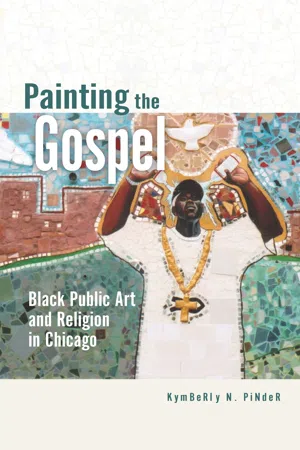

1.1 William E. Scott, Life of Christ, oil on canvas, 1936–37. Pilgrim Baptist Church, Chicago (now lost). Photo courtesy of Jeanine Oleson.

Through these connections Austin became the leading black Christian nationalist figure beginning in the 1920s. When he was not yet forty years old, in 1926 he became the pastor at Pilgrim Baptist, where he would remain until his death in 1968. Pilgrim’s congregation was large and grew along with the city’s black population. Between 1920 and 1945, Chicago’s South Side witnessed an increase in its African American population of more than 200 percent as people migrated north in search of better lives. By 1930 Pilgrim (figure 1.2) was one of the ten largest churches in the United States.5 Austin was such a dynamic preacher that people lined up hours early to get good seats for both of his Sunday services. His sermons were broadcast on the radio, and, it was rumored, he had to remove his notes quickly from the pulpit after he spoke to prevent aspiring young preachers from stealing them. Austin’s appeal was not only his oratory power but also the social content of his sermons.

Austin took the helm of the church only four years after the congregation had moved into a former synagogue. Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler had designed the building between 1890 and 1891 for the oldest Jewish congregation in the city, Kehilath Anshe Ma’ariv. As demographics changed and Bronzeville, the area between 12th and 51st streets, became predominantly African American, Pilgrim’s bought the synagogue in 1921. The architects had designed the building in an auditorium-style format with impeccable acoustics to accommodate one of the city’s largest Jewish congregations and to provide a venue for speakers and performers. In keeping with Jewish religious restrictions on representation, the space had very little ornamentation outside of Sullivan’s signature terracotta foliage, which gave it a grandeur similar to that of his Auditorium Theater located downtown.

1.2 Russell Lee, In front of Pilgrim Baptist Church on Easter Sunday, photo, 1941. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By the late 1930s Pilgrim Baptist had constructed a new gymnasium, a community center, and a housing project. Austin had turned the church into a resource for welfare, education, health care, and job training.6 The church had also begun to establish several missions in African countries and soon ranked as the Baptist Church’s third-largest contributor to foreign missions.7 Africa was a central concern for Austin, and he was elected chairman of the Foreign Mission Board in 1924, right before he became pastor at Pilgrim. In 1950 he traveled to several West African countries, and during this trip reported seeing the realization of many of the Afrocentric goals he had worked toward at Pilgrim: “I saw and counselled with a black president and a black secretary of state. … I saw black clerks and managers working in stores and black officials high in government everywhere I went. I went to Africa only to be convinced that not only the hope of the black man, but the hope of peace and the hope of the world rests in Africa.”8

In addition to commissioning Scott to cover Pilgrim’s walls with paintings, in 1932 Austin hired Thomas A. Dorsey (1899–1993) to be the church’s musical director. Known as the grandfather of gospel, Dorsey fused sacred music and the blues, often premiering new songs performed by such singers as Ma Rainey and Mahalia Jackson at Sunday services. Soon after migrating to Chicago from Georgia, Dorsey, the son of a preacher, had had a successful career as the blues pianist and composer Georgia Tom. Before a series of religious conversions, he had gained wide acclaim for such carnal songs as “Tight Like That” and “You Got That Stuff.” The importance of Dorsey and the freedom he had to develop his music at Pilgrim cannot be overstated. It was at Pilgrim that Dorsey took a young Jackson under his wing, helping her hone her voice to serve this new type of black music. She became one of his promoters, performing his songs on the corners of Bronzeville while Dorsey sold the sheet music. His gospel anthem “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” written about the death of his wife and baby during childbirth, launched her career and cemented his as a gospel composer.9

In countless interviews, Dorsey told the story of how many pastors in Chicago threw him out when he introduced compositions that caused such fervor among the congregants because they considered it unholy “alley junk,” too closely tied to the sexually charged blues played in the nearby clubs and gin joints.10 Austin, understanding the importance of the appeal of this music, especially for his younger congregants and those most recently relocated from the South, welcomed Dorsey, whose family had been members of Pilgrim since 1914. With Pilgrim as his base, by 1933 Dorsey had founded the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses and held the first National Convention of Gospel Choirs at Pilgrim. Although Austin was a university-trained, old-line pastor who went so far as to relegate the unstructured, preworship services to the basement, he was still widely known for his electrifying sermons. Religious historian Wallace D. Best has suggested that Dorsey’s gospel programs encouraged Austin to perform more “mixed-type sermons” that combined prepared written lectures on the scriptures with extemporaneous and emotive passages. With the great influx of southern migrants, Chicago’s pastors had to resist or adapt to their congregations’ changing demographics. Some church leaders crafted a hybrid or “mixed-type” style of preaching that was a “performed sermon” which “satisfied the intellectual elite, convinced the skeptic and … electrified the washer woman.”11

Dorsey and Gospel’s Sonic Realism

Gospel blues, like “mixed-type” preaching, appealed to the southernness in both the newly migrated and the urban African American churchgoer. The blues and preaching had traditionally been linked in black rural culture. As gospel historian Michael W. Harris writes:

The blues soloist was the figure in traditional Afro-American culture responsible for emoting and otherwise expressing feeling to the group through music. Another individual, the preacher, was likewise responsible to a group, but he communicated through speech. … One sang in a secular setting; the other spoke in a religious setting. But the bluesman and the preacher, beyond surface distinctions, were cultural analogues of another. The structure and delivery of sermons and blues songs bear more resemblance than dissimilarity. At the foundation of the art of each was a common creative mode: improvisation.12

Expressive singing and dancing had been commonplace in the many Holiness Pentecostal storefront churches in the city for decades. To make his fusion of blues rhythms and sacred songs, Dorsey changed a traditional hymn in two distinct ways: he played parts of it in a lower blues key, or the “blues seventh,” which is the lower seventh of the subdominant chord; and he altered the hymn’s lyrics, often writing completely new ones that used phrasing and sentiments found more often in blues music, such as drawing on everyday life to personalize religious doctrines.13 His new sound was labeled gospel blues or sacred blues, because it combined the raunchy music found in speakeasies and dance clubs with sentiments of church hymns. For example, in his first gospel hit, “If You See My Savior,” which he wrote for a mother at Pilgrim whose son had died suddenly, the lyrics mirror typical blues songs. The first few lines are:

I was standing by the bedside of a neighbor

Who was bound to cross Jordan’s swelling tide

And I asked him if he would do me a favor

and kindly take this message to the other side

If you see my Savior tell Him that you saw me

Ah, and when you saw me I was on my way

When you reach that golden city think about me

And don’t forget to tell the Savior what I said.14

The 1920s blues song “Deep River Blues” by Rosa Henderson has these lyrics:

My heart is breakin’ as I watch the evenin’ tide,

Because I’m over here; my man is on the other side. …

“Deep river! Deep river!

When I sleep beside you, I never fear;

You’ll always be, you need to be

A friend so dear,

And if you see my man, please tell him that it’s lonesome here!”15

Dorsey has simply replaced a woman longing for her man who has migrated north of the Mississippi with one longing for Jesus who is just over the River Jordan. These songs speak to each other: they are two sides of one coin. The gospel blu...