- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

'This is not a story of me, but of me and mine, of my place and theirs, of places north, south, east and west in Ireland, but particularly of home life in Dingle and holidays in Galway, and of the times and traditions that left an indelible mark on a growing boy.'

Set against the backdrop of major events in Irish history and the smaller local happenings of fair days, football matches and the first teenage dance, the book is shot through with the unique feel and flavour of an Irish upbringing.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

BONFIRE NIGHTS AND WRAN DAYS

During the round of the Dingle year there was a series of events that maintained links to generations past and created a cultural bond between the people, streets and groups in the town and its hinterland.

The two biggest traditional occasions in the year were Bonfire Night, 23 June – a pagan celebration as old as history, which the Church had hijacked and renamed as Saint John’s vigil – and the Wren’s Day, on 26 December, Saint Stephen’s Day. We called them ‘Bonefire Night’ and the ‘Wran’s Day’. From the first day of June, and sometimes much earlier, we started collecting material for the bonfire. Buggies were constructed to carry the loads, and we would go door to door, asking for wood and any other material suitable for burning, such as turf, coal and cardboard. Used car tyres, which we begged from garages or farmers, were particularly valued. The centrepiece of the fire was the baulk. This was an enormous branch or trunk of wood around which was built the fire. Getting the tree trunk was a huge challenge. Fields and farms were scoured in the search. But finding it was only the beginning. Then you had to drag it secretly into the town and store it in a place where it would be safe from marauding rival gangs who might steal it for their own fires.

Traditionally, there was ferocious competition among the different groups from the various parts of the town: Sráid Eoin, Goat Street, or the Quay. Who would have the biggest blaze? Which fire would still be burning the following day? The Sráid Eoin fire – our fire – was originally on the bridge at the bottom of Main Street. However, in later years, as people became more safety conscious, it was shifted over to the Spa Road. Building the fire would begin in the mid-afternoon. It was no easy job keeping the baulk upright; we jammed smaller logs and branches around its base for stability. Then we surrounded it with the old car tyres. Oil-soaked rags, cardboard, wood shavings and sawdust were pushed into the spaces, and outside of these were placed the additional oddments and fuels. By the time the pyre was built and set it might be twelve feet high. The fire would be lit round about eight o’clock. Torching the fire was a ceremony in itself. A number of tin cans would be affixed to rigid lengths of wire, approximately a yard long. The cans were filled tight with oil-soaked sawdust. Once they were alight they were pushed deep into the pyre to get it lighting from the inside out. The flames from the blazing wood and fuels would leap towards the sky, shortly to be obscured by the thick, black, pungent smoke from the tyres. Eventually, the logs and the baulk itself would take hold and the fire would settle down.

The townspeople went from fire to fire. Then they would bring out chairs and sit around the blaze; how far back they had to set the chairs was another measure of the power of the fire. New potatoes were produced, to be baked in the fire. You had to be fairly hardy to brave the furnace-like heat and get close enough to place the potatoes on the fire and then retrieve them. Only rarely were they properly or fully cooked, but nonetheless everyone remarked on how good they were that year, and what a great night it was.

Then the music would begin. This was music without frontiers: a hornpipe followed by rock ’n’ roll, or the twist, or whatever took the fancy. On great town occasions like this, Patrick Cronesberry and his sister Mary Ellen would sometimes perform a wild rock ’n’ roll dance. He would throw her over his shoulder, pull her back between his legs, swinging, jiving and lifting her high up in the air, moving more spasmodically than rhythmically, but giving his all to the sound of Bill Haley’s ‘Rock around the Clock’. The crowd loved it and it probably marked the beginning of my lifelong love affair with rock ’n’ roll. Once, when I was watching a Rolling Stones concert, it struck me that Cronesberry was not that different from Jagger!

The Cronesberrys were an interesting family who were originally from England. Patrick’s older brother John was the town crier. He would go around the town, ringing his bell and shouting notice of an upcoming important meeting or entertainment. He had a clipped and distinct style of speech and a very loud voice so was well equipped for the job. The sound of his bell and his resonating voice brought people rushing to their doors to hear the news. It would usually be about Duffy’s circus or a travelling fit-up show, but I do recall him announcing a meeting to oppose the proposed Turnover Tax, a predecessor of Valued Added Tax (VAT), which caused great grief to retail shopowners, who led a national campaign against it. Amazingly enough, the measure was passed in Dáil Éireann by Seán Lemass’s minority government. Fianna Fáil supporters, including my uncle Plunkett in Lettermore, swore that they would never vote for the party again and that it meant the end of the small operator – they did and it wasn’t. Lemass was gutsy and he knew that the issue of local shopkeepers having to pay tax more efficiently was not going to bother most ordinary people.

The Turnover Tax protest meeting was of interest only to the shopkeepers and small traders. This lack of interest was of such annoyance to one shopkeeper that he hired a loudspeaker system for the roof of his car and spent an hour touring the town, announcing the meeting, denouncing the Government and pronouncing the end of commerce as we knew it if this appalling tax were to be introduced. He coaxed and persuaded people to attend the meeting. ‘Come along and support us. Please be there. This is a very important meeting. Everyone is welcome.’ Of course, by the time he had said this for the twentieth time he was in foam of enthusiasm. He got quite carried away with indignation and righteousness, so much so that on his final round-up he announced: ‘Everyone must be there, and anyone who isn’t can fuck off for themselves!’ In those days that kind of language would never be broadcast over a public address system. He was the talk of the town for ages.

Patrick Cronesberry worked in the coal yard at Atkins’, one of the biggest general stores in town. In fact, they had shops in a number of locations throughout Munster. His daily grind involved lifting half-hundredweight bags of coal from store to truck and from the truck into people’s houses. To save his clothes, he usually wore a jute sack on his head, with the stitched corner sticking up like a monk’s habit and the rest stretched down his back. It was hard, dusty and thirsty work, never more so than on the couple of occasions each year when the coal boat would dock at the pier with a cargo of coal. Every available horse and cart in the town would be recruited to move the coal from the pier up to Atkins’ yard at the top of the Main Street. A huge bucket crane swung across from the boat and deposited the coal into the carts that were queued up from the quay right down to the head of the pier. As soon as they were filled, the carts trundled their way through the streets of the town to where the workers with their shining coal shovels were waiting to offload and bag the coal. It was non-stop, physical, backbreaking work, with every breath contaminated by the swirling black coal dust. There were no masks or protective clothing, so they undoubtedly inhaled black lung and other respiratory problems.

Patrick Cronesberry would come into Foxy John’s bar every evening after work. His order was always the same, ‘A flagon of Bulmer’s cider and a pint glass, Joe boy.’ He was the only person in Dingle to call me Joe. I never told my mother.

‘The Wran’ was the biggest day of the year in our young lives. No other day came close. Paguine Flaherty’s pub was the base for the Green and Gold Wran from the Holyground. The Green and Gold was always considered the best overall, for music, colour and spectacle. They would have spent weeks in preparation in Paguine’s. I used to envy my first cousins, Etna, Mazzarella, Fergus and Kar l–they were right in the middle of the action. Masks, hoods, straws and other costumes were made up; fifes were softened for practice; drums were tightened and banners were painted and sewn. There was absolute secrecy because there was huge competitiveness among the Wrans.

Our local Wran was the Sráid Eoin. The ‘Kerryman’, a huge, gentle giant of a man, was the driving force, even though young Maurice Rohan was emerging as the leader. It was in Rohan’s pub that the Sráid Eoin met for practice and arrangements. Maurice made sure everything was under control. Even when he became a teacher and moved to West Clare, he still returned each year to take charge of the Sráid Eoin Wran. But West Clare also got the benefit of Maurice’s organisational skills, as he went on to be one of the founders and main organisers of the Willie Clancy Summer School.

There were other Wrans – from Goat Street, The Quay and Milltown. Some were imaginative in deciding a theme for their group. Others were better at the music. Wrans from outlying areas, especially Lispole and Ventry, came into the town. Each had its own carefully respected traditions. In the Sráid Eoin Wran the hobbyhorse was central. It was made from light, curved, wooden hoops shaped like the torso of a horse. A white sheet covered the main trunk, the tail was stuck on the back, a carved head lead at the front, and the whole thing was carried on the shoulders of one of the Wran members who had a rope stretching back from the horse’s mouth, which he could aggressively snap open and shut at passersby or at other Wrans.

All the Wrans did at least two rounds of the town. They each had favourite pub stops where they took a sos. It was the leader’s job to make sure that they regrouped after a drink and continued on to the next ‘filling station’.

The cry ‘Fall In’ was the signal to get outside and into band formation. The more stops they made the harder it was to get them restarted. You could hear the leader cursing at the lads in the bar.

‘For fuck’s sake lads, fall in.’

But he lost a few at each stop, and by early afternoon there was drink flowing in every one of Dingle’s fifty-six pubs. Essentially, the Wran was a celebration to mark the passing of the shortest day of the year, and it was as old as mankind. It was the defeat of winter and the optimism of the coming spring, with its lengthening days and benign weather. Nowhere was this more evident than in the defining and defiant cry of the Sráid Eoin Wran: ‘We never died a winter yet. Up Sráid Eoin.’

Things would be well heated up by the start of the second round of the town. Drink was taking effect. Even without the alcohol people were intoxicated by the music, the shouting, the dancing and the occasion. Inhibitions were lost. Nobody recognised anybody under the hoods and masks. It was a time when it was okay to grab a woman and feel her in ways that at any other time would have been out of the question. Anonymity gave protection.

If the first circuit of the town was for entertainment, the second was for the collection. The man with the collection box was crucial. People at their windows, usually upstairs to get a better view of proceedings, would throw down their contributions to the collector. Shopkeepers and merchants were watched carefully to ensure they paid up, and the givers were careful to make sure that they gave something extra to their local Wran.

In those days the collection was for the Wran Ball. Well, it was called a Ball, but it was another excuse for a great drinking session. Towards evening time there was the last round-up. This was where all the Wrans and the various bands came together for one final tour of the town. It was marvellous. The streets streamed with colour and resounded with music, dancing, shouting, singing.

There was no time quite like it. Your blood would be pounding through your veins and the small hairs standing on your neck with sheer excitement and emotion. Dingle that day was like no other place. It was wild, mad, drunk and pagan. Pagan in the symbolism of the straw men and the hobbyhorse. Menacing and theatrical in the masks and disguises. Wild and atavistic in the driving wren tunes and provocative dancing. Add alcohol to that mix and all boundaries, inhibitions and limits collapsed.

Is it any wonder that the Church was less than enthusiastic about it? This pagan day had occasions for drink, sex and a slackening of morals generally, and it diverted collections away from the Church.

Many of my family and friends still make the annual pilgrimage to Dingle to take part in the Wran, leaving their homes before cockcrow on St Stephen’s morning. Of course, it has changed and developed over the years. But it still quintessentially ‘us’. Of all my friends I am the only one I know not to have gone back for the Wran since leaving Dingle. Why? Well, my memories of the day are so great, that I am afraid that returning would corrupt the magic. Maybe, like Oisín returning from Tír na nÓg and suddenly changing into a feeble, old and babbling man, confronting the reality of four decades of change in the Wran would steal my youth, too. But the memory remains untouchable.

The Dingle peninsula, comprising town, village, country, sea and mountain, is best described by its ancient barony title of Corca Dhuibhne rather than by any of its other names, such as West Kerry, which makes it seem just a portion of a greater integrity.

It is often said of the peninsula – the most westerly point of Europe – that ‘the next parish is America’. There is something casually dismissive about that description that I don’t like; does it imply that Dingle was ‘the arsehole of Ireland’, or at the very least a twilight zone between the real Ireland and the vast ocean? We who were born between Blennerville bridge and the Blasket Islands have a different perception. When we stand on Coumenole or Clogher strands, addressing the Atlantic Ocean, and with the land mass of two continents guarding our backs, we truly feel that we are the vanguard of Europe. Slea Head and Dunmore Head, cleaving aggressively into the Atlantic Ocean, give direction to the continent of Europe.

Yet Corca Dhuibhne is more an attitude than a place. Its mark is indelible; there is no leaving it behind. No matter how far we journey, that attitude travels with us and influences and informs what we do throughout our lives. We are unnaturally and irrationally proud of our birthplace

The peninsula is an elemental place, open to the vagaries and moods of Mother Nature. On a bright summer’s day, when the sun, sea and scenery are in harmony, it is a perfect heaven. In winter, the sight of fearsome Atlantic waves charging ahead of a southwestern storm and smashing against the fastness of the rocky headlands and cliffs is an awesome and exhilarating experience. Then again, ther...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- DEDICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- FOREWORD

- CONTENTS

- CAST OF CHARACTERS

- DADDY TOM

- SEÁN THE GROVE

- CONNEMARA ROOTS

- THE EMIGRANTS’ RETURN

- GRANNY AND HER SISTERS

- A KERRY–GALWAY MATCH

- A KICKSTART FROM THE POPE

- ‘UNWILLINGLY TO SCHOOL’

- FOXY JOHN

- SUMMERS IN GALWAY

- UPSTAIRS IN THE MONASTERY

- FAIR DAY IN DINGLE

- BURIED TALENTS

- THE BEST OF TIMES, THE WORST OF TIMES

- BEHIND THE COUNTER

- THREE CHEERS FOR OUR LADY OF FATIMA

- JIMMY TERRY’S STALLION

- A TAILOR ON EVERY STREET

- BONFIRE NIGHTS AND WRAN DAYS

- LIGHT MY FIRE

- THE BEST OF TIMES, THE WORST OF TIMES

- ANYTHING BUT A SOCIALIST

- GOODBYE DINGLE, HELLO DUBLIN

- Plates

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

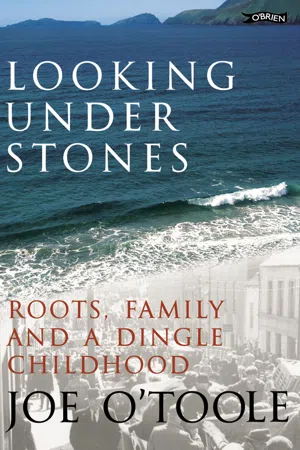

Yes, you can access Looking Under Stones by Joe O'Toole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.