![]()

THE MODERN BRICKLAYER

VOL. III

CHAPTER I

PREVENTION OF DAMP

CAUSES OF DAMPNESS. SITE PROTECTION. VERTICAL DAMP-PROOF COURSE. PARAPET WALLS. FLAT ROOFS. LEAKY PIPES. SPECIAL TYPES OF DAMP-PROOF COURSES: Blue Staffordshire Bricks—Ruberoid —Sheet Lead—Asphalt—Slates—Glazed Earthenware—Cement and Sand—Sand and Pitch. INSERTING A DAMP-PROOF COURSE IN AN EXISTING WALL. KNAPEN SYSTEM OF DAMP-PROOFING. POINTING. CONDENSATION. CAVITY WALLS: Ties—Building Cavity Walls—Examples of Cavity Wall Construction.

ONE of the main objects of modern sanitation is to prevent or mitigate dampness in buildings of every description. Dampness not only deteriorates house property, hastening its falling into decay, but is considered a primary cause of many diseases and general unhealthy conditions. It is largely preventable, for dampness in buildings can generally be traced to three causes: bad workmanship, faulty design, or inferior materials and fittings. Dampness can only be prevented or cured when sound materials are used by good craftsmen with a special knowledge or under expert guidance.

CAUSES OF DAMPNESS

The causes of dampness are many, though most of them can be grouped under four divisions:

(1) Bad drainage of the ground under and surrounding the building; the omission of, or bad construction of, horizontal and vertical damp-proof courses; faulty construction, or faulty materials, used in laying the site concrete; faulty gullies and drains attached to buildings. All these lead to dampness rising from the ground upwards.

(2) Rain beating against the faces of walls; defective or broken water pipes, waste pipes, or water heads; the omission or bad construction of vertical damp-proof courses—all of which lead to dampness entering the building in an horizontal direction.

(3) Defective or badly constructed damp-proof courses attached to parapet walls, etc.; leaky or blocked gutters; badly constructed roofs, or roofs out of repair—all of which cause the dampness to creep downwards.

(4) Faulty fittings, defective or burst pipes, inadequate supply or size of waste and overflows, which distribute dampness in awkward and unforeseen directions.

In all these cases dampness is induced or accentuated by the law of capillary attraction, which for our present purpose we may define as the porosity of materials.

Another very unpleasant but less dangerous form of dampness is due to condensation, caused by the deposit of moisture in the atmosphere on a colder, hard, dense and usually polished or smooth surface. Thus, under certain weather conditions, walls, either inside or out, may be dripping with water. Though difficult to cope with, even this can be modified.

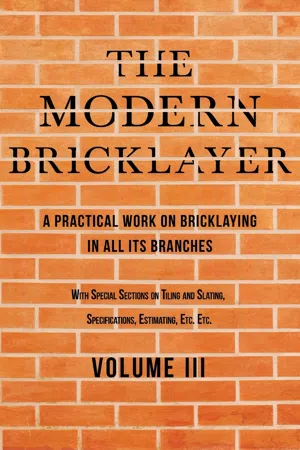

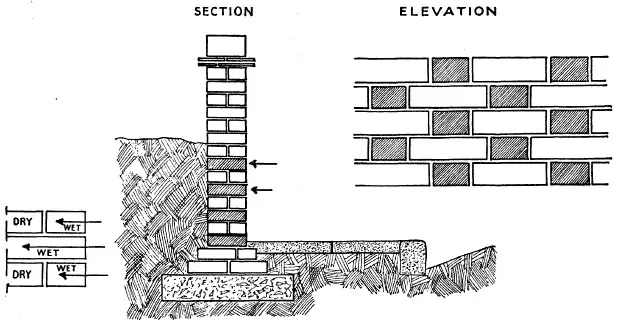

FIG. 1.

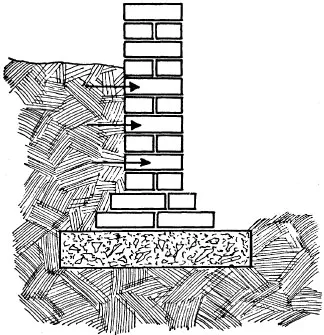

FIG. 2.

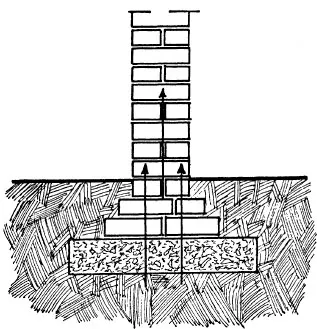

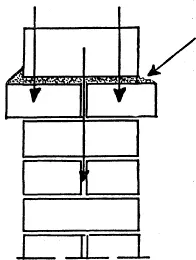

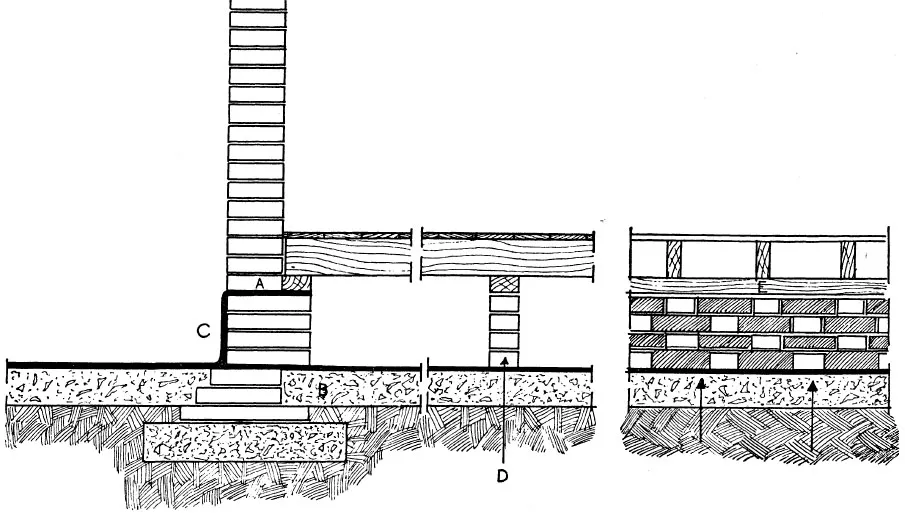

The horizontal progression of dampness through a wall is shown in Fig. 1. In this case it is due to the absence of a vertical damp-proof course between the external face of the wall and the wet earth at the back, whence the dampness, meeting with no obstruction, penetrates and spreads. Similar cases are often met with in connection with boundary walls, garden walls and house walls, where the level of the ground is much higher than the level of the house, as in basements, houses backed against hills or banks, etc. The section of a 9-inch wall, with footings and concrete seal, where the dampness is spreading upwards, is shown in Fig. 2. In this case there is no horizontal damp-proof course to obstruct the rise of moisture, probably drawn from the earth at the sides of the footings, and even through the concrete. If the concrete is spongy, open in texture, even though made with the best of materials and waterproofed, moisture will rise through, attracted by the warmth and dampness above it. On the other hand, if the concrete were absolutely impermeable, dampness would be drawn from the wet ground by the footings. In Fig. 3 we have the section of a wall where dampness is travelling downwards from the top brick on edge course through the wall, which would happen if inferior mortar or porous bricks were used in building the course. It would also occur if the joints were not solidly filled, or if the fillets on the projecting courses decayed owing to atmospheric conditions or the use of bad materials, when a ledge would be left for the rain to settle on, and find its way into the brickwork, as indicated by the arrow. In Fig. 4 we have the section and portion of the elevation of a 9-inch boundary wall, with a brick on edge and tile-creasing course. This particular wall, which the author had occasion to examine, was showing on its face dampness of a peculiar nature. It was due to moisture penetrating through the wall from the earth in the garden, which was on a much higher level than the pavement on the external face of the wall. There was no vertical damp-proof course on the inside of this boundary wall to protect the internal face from the very moist bank of earth behind it. It was obvious that the dampness came from the earth at the back, but the peculiar point was that this only showed on the faces of the majority of headers, whilst the stretcher bricks between them were in a particularly dry state. The reason for this can be better understood by referring to the detail in the left-hand diagram Fig. 4. This shows a small section of the wall with three courses of the brickwork. The thick lines represent the horizontal bed joints and the vertical wall joints. The centre arrow represents the header, and it will be seen that the dampness could pass through this brick (especially if of a porous character) from the internal to the external face of the wall. The arrows placed horizontally above and below the centre one indicate the stretchers on the back face of the wall, which were wet, so the dampness had passed through them. This dampness penetrated up to a certain point, the wall joint between the back and front stretchers; and not being able to proceed farther on account of this joint, composed of cement and sand, it had to take a different direction. What happened was that this vertical wall joint and the top and bottom horizontal joints formed a watertight cell or pocket, protecting the external stretchers from the moisture, and so they are marked as dry on the diagram. But having to find a way out, the moisture penetrated the headers, or “through” bricks. This, of course, might occur in the wall of the building, and be aggravated by the difference of temperature inside and out. A suitable cure in such a case would be to construct a vertical damp-proof course attached to the back face of the wall, and so prevent the dampness penetrating the brickwork from the earth.

FIG. 3.

FIG. 4.

A weak place in many small houses is the bay window on the ground floor, where considerable dampness frequently shows at the base, and may spread widely from there. In the majority of cases it will be found that these bays have no horizontal damp-proof courses. At other times the defect may be due to bad paving round the base of the bay, or occasionally to earth being piled up to a level above the damp-proof course. A too-common attempt to cure this nuisance is to render the face of the wall with cement mortar. This may be perfectly watertight as regards the face of the wall, but does not touch the real source of evil, the dampness at the foot of the wall, which penetrates below or at ground level and spreads upwards through the wall.

The precise form of cure for this manifestation of dampness can only be found by thoroughly examining the wall and its surroundings, with a view to ascertaining (1) whether the wall has an horizontal damp-proof course or not, and if not, to insert one; (2) the position of the damp-proof course if existent. Such course should not be less than 6 inches above the level of the ground.

If lower than, or below, heaped-up soil, the soil should either be removed to a lower level, or a vertical damp-proof course built on the external face of the wall. Such a vertical course should extend 3 inches below the level of the horizontal damp-proof course and 6 inches above the level of the surrounding ground. This would prevent dampness from rising in a vertical direction in the wall, while at the same time dampness would be prevented from gaining access in an horizontal direction from the surrounding ground. This is a good illustration of the effective combination of the two systems to meet a threat from two directions.

FIG. 5.

SITE PROTECTION

Fig. 5 is the section of a wall showing the various positions of the damp-proof courses. Starting from the base, the site bed of concrete is shown. This must be of good materials, properly gauged and well laid. This is important for all buildings, but particularly as regards dwellings. The site concrete should be composed of a good cement, with the addition of suitably graded aggregate, such as Thames or other river ballast, or clean broken bricks, and clean sand, waterproofing material being added either to the dry cement or in the gauging water. It should be well mixed dry, and thoroughly worked, but not overworked, when gauged. This should be solidly laid all over the whole site, so as to form an impervious seal, which will prevent dampness from the soil rising through it into the space beneath the floor. The ground is almost always damp, at some times markedly so, not always from rain in the immediate neighbourhood, but often from the fluctuations of the level of the ground water, which may be fed from some distance. If the site is not pr...