![]()

1

LONDON

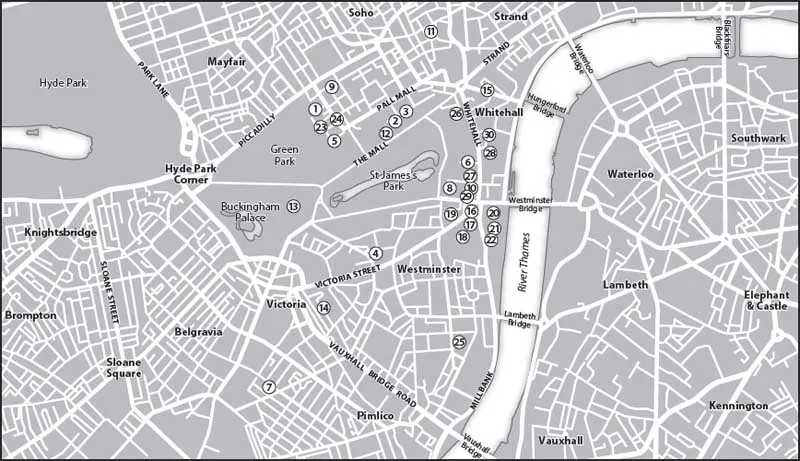

SW1

“London was like some huge prehistoric animal, capable of enduring terrible injuries, mangled and bleeding from many wounds, and yet preserving its life and movement.”1

In 1954, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, were returning from a Commonwealth tour on the Royal Yacht Britannia. Winston Churchill, in his eightieth year, was prime minister and joined the yacht when it was in British territorial waters and together they sailed to London. The queen saw the Thames as a dirty commercial river, but, as she said, Churchill “was describing it as the silver thread which runs through the history of Britain”.2

Churchill had more to do with London than with any other city. He went to secondary school on the outskirts of the capital but, from the beginning of the century, he always had a home in London. Over a third of the locations celebrated in this book are found in London, so I have divided the city into two. First we have the postal area of SW1, which covers the City of Westminster – the centre of Britain’s political life – and the socially elite area to the north.

1. Arlington Street, p.6

2. 4 Carlton Gardens, p.6

3. German Embassy, p.7

4. Caxton Hall, p.8

5. Stornoway House, p.9

6. Downing Street

10 Downing Street, p.12

11 Downing Street, p.17

7. 33 Eccleston Square, p.20

8. Cabinet War Rooms, p.21

9. 71–72 Jermyn Street, p.28

10. King Charles Street, p.28

11. Empire Theatre, p.29

12. The Mall, p.30

13. Buckingham Palace, p.31

14. Morpeth Mansions, p.32

15. Northumberland Avenue, p.35

16. Parliament Square, p.40

17. St Margaret’s Church, p.41

18. Westminster Abbey, p.44

19. Methodist Central Hall, P.45

20. Big Ben, p.45

21. House of Commons, p.45

22. Westminster Hall, p.55

23. St James’s Place and St

James’s Street

29 St James’s Place, p.56

6 St James’s Street, p.57

9 St James’s Street, p.57

19 St James’s Street, p.57

24. The Carlton Club, p.59

25. Westminster Gardens, p.59

26. Admiralty House, p.59

27. Foreign Office, p.64

28. Home Office, p.65

29. The Treasury, p.66

30. The Old War Office, p.67

Arlington Street

21 Arlington Street

USEFUL ARISTOCRATIC CONNECTIONS

Arlington Street was part of the early development of the fashionable St James’s quarter of London. It was originally built in the late seventeenth century.

Although there is no plaque, the street featured the London home of the third Marquess of Salisbury, prime minister when Winston Churchill first became a Member of Parliament in 1900. Lord Salisbury was an intellectual, a dabbler in amateur chemistry and, in his earlier days, an essayist dealing with political history. He had just about pushed Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph, out of the cabinet in 1886, and there was a brittle relationship between the older man and the young Churchill. But Salisbury was generous and took a paternal interest in him. Salisbury’s son, Lord Hugh Cecil, became a close friend of his, and was best man at his wedding in 1908. While Churchill was still a Conservative – until 1904, that is – he used to spend time with Lord Hugh Cecil and others who formed an awkward squad known as ‘the Hughligans’.

Not far away is Number 21, a house with a forecourt. Formerly known as Wimborne House, it was the principal London home of the family of Viscount Wimborne, Churchill’s cousin (Wimborne’s mother was a sister of Lord Randolph Churchill). Wimborne’s son, Ivor Guest – successively a Conservative and Liberal MP – made Wimborne House available to Churchill and his family after he ceased to be First Lord of the Admiralty in 1915.

Carlton Gardens

4 Carlton Gardens

CHURCHILL AND DE GAULLE

Carlton Gardens and Carlton House Terrace were built in the 1820s, designed by John Nash to replace Carlton House, the residence of the Prince Regent, later King George IV. Both streets became the homes of the ‘new rich’ – the ‘old rich’ already had their houses to the northwest, in Mayfair and Belgravia.

Next to the gardens is a statue of General Charles de Gaulle, uniformed and with one hand outstretched. A junior minister when France capitulated in June 1940, de Gaulle slipped out and came to Britain. Here, he became the leader of the Free French, directing a consistent resistance to Nazi-occupied France. This address, as a plaque indicates, was the headquarters of France Libre.

Winston Churchill welcomed de Gaulle and gave him resources and moral support. But over the years they had a prickly relationship. Both men saw themselves as personifying the ideals and the history of their countries.

Carlton House Terrace

German Embassy

APPROACHED BY HITLER’S MAN IN LONDON

The German Embassy lies alongside the Waterloo Steps, which descend to the Mall, the long, majestic road leading from Trafalgar Square to Buckingham Palace. In 1937, Winston Churchill was invited to a meeting with the ambassador there, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Ribbentrop was a familiar personality in London’s upper-class social circles, and Churchill had met him several times before. Churchill was received in a large room on an upper floor, and their conversation lasted for over two hours. Ribbentrop argued that Germany sought only friendship with Britain and its empire, but that it must have Lebensraum – living space – to the east for its expanding population. Churchill, who was not a government representative at the time, argued that Britain could not give Germany a free hand in Eastern Europe, even though Britain detested Soviet Communism as much as Hitler did.

Ribbentrop later became German foreign minister and negotiated the Nazi–Soviet Pact of 1939 with his Soviet counterpart, Molotov. After the war, he was found guilty at the Nuremberg trials and sentenced to death.

Caxton Street

10 Caxton Street, Caxton Hall

A CELEBRITY BY-ELECTION

Found at the heart of Westminster, the red-brick Caxton Hall has witnessed many important political events. In March 1924, the results of a by-election were declared here: Winston Churchill lost.

Before the reform of the parliamentary electoral system in 1832, the Westminster parliamentary constituency was the most democratic of English constituencies: almost all of its adult male constituents had the vote. What is more, because of its central metropolitan location, it always attracted attention. In 1780, Westminster had 12,000 voters who, after a riotous election, returned Charles James Fox as Member of Parliament. The following century, the philosopher and early advocate of women’s rights John Stuart Mill was MP for Westminster.

In 1924, Winston Churchill was edging away from the Liberal Party and towards his first allegiance, the Conservative Party. He stood in the by-election as an independent, anti-socialist Constitutionalist. He had been a Liberal MP (and minister) until 1922, and he had fought and lost an election at Leicester in 1923. He had campaigned ferociously against the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and saw no great difference between Soviet Communism and the gentle English socialism of the Labour Party which, in January 1924, had formed the first Labour government under Ramsay MacDonald. In this by-election, Churchill was not endorsed by the Conservative Party, who put up their own candidate, but he was supported by individual Conservatives. In effect, he was splitting the right-wing vote. This displeased the ‘Conservative machine’ and contributed to the deep distrust that many Conservatives had for Churchill over the next twenty years.

The Westminster constituency was called the Abbey division, and it included Westminster Abbey, Victoria station, Pall Mall, Drury Lane and Covent Garden. It was reckoned that, in 1924, over one hundred Members of Parliament lived within the constituency, as well as “dukes, jockeys, prize-fighters, courtiers, actors and businessmen”.3 Among these distinguished constituents was the playwright George Bernard Shaw, who got on well personally with Churchill. Shaw thought Churchill had been right about the disastrous Gallipoli campaign but, as a socialist, he voted for the Independent Labour Party candidate, Fenner Brockway. Another constituent was the former prime minister and leader of the Conservative Party, Arthur Balfour, who issued a letter backing Churchill. But Westminster was not home to wealth alone: there was a working-class element around Horseferry Road. As well as Otho Nicholson, the official Conservative candidate, a Liberal stood.

The by-election became an entertainment. Churchill had the enthusiastic and resourceful support of a new friend, a twenty-three-year-old red-headed Irishman with a flair for promoting himself and Churchill. His name was Brendan Bracken. He organised a coach and four horses to take his candidate around the constituency. Chorus girls came to address envelopes for circulars for constituents and deliver election addresses.

The glamour did not win against the machine. Nicholson was returned with a majority of forty-three over Churchill. Brockway came a reasonable third, and the Liberal at the bottom of the poll. At the count, Brockway recalled, the first indications were that Churchill had won. But when his defeat was confirmed, his spirits slumped. His hopes of returning to the House of Commons were dashed. He shared his disappointment with the Labour candidate: “You know, Brockway, you and I have no chance. We represent ideas – Nicholson represents the machine”.4

Later that year, Churchill managed to get a constituency and the backing of the Conservative Party: Epping, a constituency he held for the rest of his parliamentary life.

Cleveland Row

Stornoway House

MAX BEAVERBROOK, HIS OLDEST FRIEND

Tucked away to the west of St James’s Street is an eighteenth-century mansion, Stornoway House. On one side, it overlooks Green Park, giving it an almost rural air; on the other, it overlooks St James’s Palace. The house was built in the 1790s for the first Lord Grenville, a future prime minister. Today, it accommodates the offices of a financial house.

From the early 1920s, Stornoway House was the London home of Lord Beaverbrook, a friend of Winston Churchill from before the First World War until the 1960s, and Churchill was an occasional guest here before the Second World War. Beaverbrook and Churchill were both allies of King Edward VIII at the time of his abdication, and Churchill dined here on 2 December 1936, during the abdication crisis, to discuss the king’s situation.

The political and personal lives of Churchill and Beaverbrook interacted over the decades. Beaverbrook, born Max Aitken in 1879, was a Canadian, the son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister. He came to London before he was thirty years old, by which time he was already a multi-millionaire, riding on the crest of Canadian development and his native country’s early-twentieth-century prosperity. He made his money in steel and cement, in the development of the West Indies, and in finance. After he arrived in London, Aitken had an extraordinary career. He became an ally of the Unionist (Conservative) Member of Parliament Andrew Bonar Law – also born in Canada – who became the leader of the Conservative Party in 1911. Promotion and honours were showered on him: Aitken effortlessly became the Conservative MP for Ashton-under-Lyne in Lancashire, was knighted, made a baronet and then became a peer, taking his name from a stream in New Brunswick – Beaver Brook. He became at the centre of British public affairs, an ally of senior politicians and instrumental in the accession of prime ministers Lloyd George in 1916 and Bonar Law in 1922. Lloyd George made Beaverbrook minister of information in 1917, and so he became a privy counsellor before he was even forty years old. At the end of the First World War, he bought the Daily Express newspaper, and it is as a newspaper proprietor – though he preferred to see himself as “principal share-holder” – that he is best known. He founded the Sunday Express and was a regular contributor to his own newspapers; indeed, he described himself on his passport as a journalist.

Beaverbrook and Churchill held each other in mutual regard. Churchill’s closest friends were mavericks and, like Beaverbrook, not from the same upper-class background – Brendan Bracken and Professor Lindemann were similar outsiders. Beaverbrook and Churchill both had a sense of fun, even mischief. Both enjoyed their alcohol, and both had strong interests outside politics. Both had close friendships across the political spectrum. Both were serious historians. Beaverbrook always had access to Churchill. As Franklin D. Roosevelt’s confidant, Harry Hopkins, said, Beaverbrook was a man “who saw Churchill after midnight”.5 Clementine Churchill was, however, no fan of Beaverbrook, whom she referred to as “Bottle Imp”.

They did not always see eye to eye. Beaverbrook was critical of Churchill’s desire to snuff out the Bolshevik Revolution after 1917 and of his role as chancellor of the exchequer between 1924 and 1929; nor did he join in Churchill’s campaign for rearmament in the 1930s. But with the outbreak of the Second World War, the old friendship bloomed. Churchill wanted Neville Chamberlain to make Beaverbrook minister of food and, when Churchill became prime minister on 10 May 1940, he looked to Beaverbrook for comfort and support. They lunched together – just the two of them – on 11 May and again the next day. And, on the evening he finally moved from Admiralty House to 10 Downing Street in June 1940, he even spent the night at Stornoway House. He brought Beaverbrook in as minister of aircraft production. But Churchill also seemed to depend on Beaverbrook for emotional support. When he made his fourth visit to France in the five weeks after he became prime minister – a visit that saw the collapse of morale of the French leaders – he took Beaverbrook with him.

Beaverbrook was an unorthodox minister in 1940. Stornoway House became the first offices of the Ministry of Aircraft Production, and Beaverbrook recruited businessmen and staff from his newspapers, who were unpaid. Beaverbrook’s drive and dynamism built up the country’s arsenal of shells and guns as well as fighter aircraft, which were a key factor in the Battle of Britain later in 1940. At this time, the two men were very close. One evening during the Blitz in 1940, Churchill and Beaverbrook gazed out of Stornoway House’s large windows overlooking Green Park. They watched flashes of guns and the glare of an exploding bomb. Even Churchill thought they were taking needless risks, and they moved across central London to the ICI building on the South Bank, fro...