- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

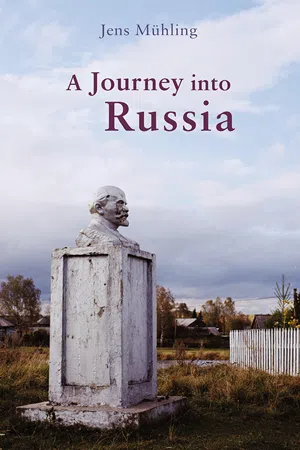

A Journey into Russia

About this book

When German journalist Jens Mühling met Juri, a Russian television producer selling stories about his homeland, he was mesmerized by what he heard: the real Russia and Ukraine were more unbelievable than anything he could have invented. The encounter changed Mühling's life, triggering a number of journeys to Ukraine and deep into the Russian heartland on a quest for stories of ordinary and extraordinary people. Away from the bright lights of Moscow, Mühling met and befriended a Dostoevskian cast of characters, including a hermit from Tayga who had only recently discovered the existence of a world beyond the woods, a Ukrainian Cossack who defaced the statue of Lenin in central Kiev, and a priest who insisted on returning to Chernobyl to preach to the stubborn few determined to remain in the exclusion zone.

Unveiling a portion of the world whose contradictions, attractions, and absurdities are still largely unknown to people outside its borders, A Journey into Russia is a much-needed glimpse into one of today's most significant regions.

Unveiling a portion of the world whose contradictions, attractions, and absurdities are still largely unknown to people outside its borders, A Journey into Russia is a much-needed glimpse into one of today's most significant regions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Long Walk to Paradise

When I think back on Agafya today, I hear her voice before I see her face. She speaks, but I do not hear any words, only an unmistakable melody. She seems to be singing. It sounds like a faint, unfinished song not intended for an audience.

For five days and four nights I heard her singing voice almost constantly. Each of its melodic variations impressed itself on me, even if I did not always understand the text. Sometimes I was not sure whether Agafya herself knew the text exactly. When she spoke, it often sounded as if her song drifted aimlessly and at random through fragments of memory and verses of scripture, through family tales and the life stories of people she had known.

When Lyonya and I set out to leave on the fifth day, the melody had become so familiar to me that I could not imagine Agafya in silence. Even today I wonder if her song pauses when there is no listener nearby, or if she continues singing – for the birches, for the bears, for herself.

I no longer remember the beginning of the song. It probably did not have one. It emerged seamlessly from the roar of the river when Agafya stood before me that evening for the first time, a tiny woman with a giant hatchet in her hand.

‘… Lyonya has come. He has brought somebody …’

She looked older and at the same time younger than I had imagined her. Her face, framed by two headscarves worn one over the other, was weathered and wrinkled with age, but Agafya smiled like a child. She could hardly have been one and a half metres tall. A floor-length dress, pieced together from dark, coarse woollen fabrics, disguised her figure, but she was clearly not very strong; her shoulders must have been smaller than the tree trunks from which her fish trap was composed. How this tiny woman had heaved the wood into the river was difficult to imagine.

‘Karpovna!’ Lyonya always addressed Agafya by her patronymic. ‘I have brought you a fine guest, Karpovna! You can tell him all of your stories!’ He spoke to her the way you speak to very old people: a little louder than necessary, a little more genially than necessary.

For a long time I had thought about how to explain to Agafya where I came from. But when I mentioned the name of my home country, a knowing smile crossed her face.

‘Germany …’ she repeated. It sounded as if she was trying to remember something. ‘There was a king, in Germany. He had a wife, but he wanted to marry another. The Pope would not give him his blessing. That was in Germany.’

I could not place the story – was she talking about Henry VIII, was she confusing Germany with England?

‘Who told you that?’

‘I read it in a book. I have many books.’

‘Show him your books, Karpovna! Why are we standing around here?’

While we walked along the river, the evening sun sank behind the mountains. The valley turned red before it paled. I was in a strange mental state, dead tired and wide awake at the same time, exhausted from the hike, electrified by our arrival. I could hardly feel the weight of my backpack anymore, everything seemed strangely light, as if the world in which I had landed was not quite real. Agafya walked in front of me, so close that I could make out the irregular seams in her dress, the dirt under her fingernails, the notches in her hatchet. I memorised every detail with the nervousness of a dreamer who knows that he may wake up at any moment.

I was only half listening when Lyonya told me the name of a smaller tributary which flowed into the Abakan just behind the fish trap: the Yerinat. We continued walking on its shore, until the dense forest suddenly opened up. A clearing wound its way up the mountainside. Three small wooden houses stood about halfway up. Above them I could make out the furrows of a potato field.

The oldest of the three huts was half-dilapidated. Agafya had lived in it until her father had died. The two other houses, which were visibly newer, had been built by Lyonya and his forestry colleagues. Agafya lived in the one on the left. Lyonya disappeared into the right one to unload our backpacks.

I unpacked the gifts I had brought along with me: the headscarf from Doctor Nazarov, the letter from Agafya’s cousins in Kilinsk, the jar with the home-pressed sunflower oil, a woollen blanket that I had bought as a gift and finally the letter from Galina, the linguist. Smiling, Agafya turned all the objects over in her hands, as if she was pondering their religious adequacy. In the end she put the headscarf, the blanket and the sunflower oil on a woodpile in front of her hut. Only the letters remained in her hands as she went inside.

A campfire was smouldering between the houses, with a pan full of fish roasting over the embers. While I was wondering who had put them on the fire, a very small man with a very long beard suddenly stood before me. He reached out his hand. ‘Alexei.’ The high voice did not fit his beard.

Alexei was a distant relative of Agafya’s. He visited her each year around this time. Usually he would stay a few weeks to help her with the winter preparations. He came from one of the Old Believer communities in the Altai Mountains. As it turned out, it was a neighbouring village of Kilinsk, the place where I had met Agafya’s cousins.

We could not talk for long. When Lyonya returned, he grabbed me by the arm and pushed me into Agafya’s hut. ‘Here, Karpovna! Tell him your stories! The man has come all the way from Germany!’

I cannot say in retrospect how long she talked that first night – two hours, three, maybe four? Outside the tiny window of the hut, darkness soon descended. Only the moon cast a trapezium of blue light on the floor, otherwise there was nothing left by which I could have measured the time. Even Agafya half disappeared in the night, I could only make out the left side of her face, the one that was lit by the moon. The narrow plank bed on which she sat was strewn with jumbled household items that I could only vaguely recognise in the dark – pieces of fabric, baskets made of birch bark, a metal tub, books, the barrel of a gun. I wondered where Agafya slept. I wondered if she slept at all.

The chaos sprawled over the edge of the bed, it filled the entire hut. The floor was littered with firewood, work tools and baskets full of germinating potatoes. Piled on a shelf were sewing utensils, and behind them three large icons leaned against the wall, their motifs unrecognisable in the darkness. Herbs were hung out to dry under the low ceiling, battered cookware lay next to a giant clay oven that took up a good third of the hut. I could hear the chewing sounds of two goats that lived in a tiny wooden box next to the stove. Their pungent smell attracted insects. It was the season of the mozhki, those tiny Siberian flies whose bites I had been warned about in Abaza. The hut was full of them. They gnawed away at my hands while I was trying to transcribe Agafya’s singing sentences into my notebook, without really seeing what I was writing due to the darkness. The only thing I could clearly make out the next morning was the figure 7453, the year of Agafya’s birth, counted by the old Byzantine church calendar.

‘… Easter fell on 6 May that year, although by your calendar it was 23 April, and you call the year 1945, but 7453 years had passed since the creation of the world …’

Sometimes she would unexpectedly reach for one of her books while she was speaking. She heaved the centuries-old volumes onto the moonlit window sill, unlocked the iron clasps, opened the worn leather covers and quickly found the passages she was looking for. The first time it took me a few seconds to realise that her chant had changed into actual singing – the shift was minimal. She sang liturgies to me, Orthodox prayers the way they had been sung before the church schism – not one hallelujah too many, not one too few.

Although she was sitting hardly a metre away from me, I sat on the edge of my stool with my body bent forward, my notepad on my knees, trying to follow her singing. That first night my pen often hovered over the paper without moving. I understood little. I had not yet grown accustomed to Agafya’s song, to the seemingly aimless drift of her sentences, to the way she stretched her words, words I had never heard, because no one used them anymore but her.

Eventually I put the notepad aside and gave up trying to wring meaning from the words. I simply listened to the sound of her voice. The very fact that she sang, that she was sitting in front of me, that this woman existed at all, was more than I could grasp in one night.

Lyonya and Alexei were already asleep when I entered the second hut. I rolled my sleeping bag out on a plank bed and crawled into it. There was a tiny window right next to my head. I looked out into the night. An almost full moon hung above the mountains, its reflection danced in the river, trembling. The Taiga suddenly seemed as bright as day. With an unreal clarity the outlines of the pine trees stood out against a sky, below which no man was awake but me.

‘Karpovna! What have you dragged in here again?’

Lyonya, Alexei and I sat eating breakfast when Agafya entered the hut. Smiling, she put a loaf of bread and a bag of prunes on the table. It was a ritual that would start each morning over the following days. Smiling, Agafya would enter the hut and bring us gifts, a sack of potatoes, a basket of cranberries or a handful of pine nuts. She never ate with us, and I never saw her eat alone; her meal times were a closely guarded secret. When she visited us for breakfast, she spoke to us without sitting down, she just stood beside the table.

Lyonya grabbed the bag with the prunes. It was a sealed plastic package, printed with colourful letters – apparently some visitor had given it to Agafya as a gift.

‘Karpovna, what are we supposed to do with this? Keep the vitamins around for the winter.’

Agafya laughed softly, as if Lyonya had made a joke. ‘But I do not eat that. It has the barcode on it.’

The word sounded bizarre coming from her mouth, like a sudden flash of colour in a black-and-white film.

‘Karpovna, don’t be silly. The barcode won’t do anything to you.’

Again she laughed. ‘John wrote that it is the sign of Satan. Earlier it was a different sign, a red star, father talked about it. Then it was a hammer and a sickle. Now it is the barcode.’

‘Agafyushka, you are looking for Satan in the wrong place.’ Alexei plucked breadcrumbs out of his beard. ‘Satan hides from us, we cannot see him. Do you know where he is hiding? In the television! I’ll explain it to you. There are 24 frames per second. But sometimes there are 25 or 26, sometimes even 31! No one can see that fast. Only the devil knows what is being shown to us there.’

For a few more minutes the conversation revolved around Satan’s hiding places. When Agafya finally left the hut, I asked Lyonya and Alexei to explain a few of her sentences to me, which I had not quite understood.

‘What is there to explain?’ Lyonya looked me in the eyes. ‘Do you think I understand her? No one can figure her out. She’s an old woman. God only knows what is going on in her head.’

Agafya’s world is small. Its eastern border is the bank of the river. To the west, the potato patch climbs up the mountainside in steep terraces, for about 100 metres, enclosed by dense Taiga. A narrow footpath leads into the forest on the southern side of the potato field, to a small wooden shed that Agafya uses to smoke fish in the summer. The only direction in which Agafya moves a little bit further away from her hut is to the north, along the river, to the fish trap. Just beyond it, a couple of willows stand by the river. Every morning Agafya cuts off a few branches here, which she feeds to her goats. She rarely goes any further north than where the willows are. All in all, her world is hardly a square kilometre in size.

For five days I was constantly at her side. We emptied the fish trap together in the mornings, cut willow branches, fed the goats. Agafya gutted the fish, I scaled them. We pulled the weeds from the potato field, we stacked firewood, we repaired the roof of the hut and mended the holes in the fish trap. Only for eating and for praying did Agafya withdraw, otherwise she accepted my presence with a naturalness that surprised me until the end. She spoke almost continuously. Her chant began in the morning, when she appeared in the guest hut with her breakfast gifts; in the evening, when we were sitting in her cabin together, she would talk well into the night. It seemed she was happy to have a listener.

Surprisingly soon, I tuned in to the sounds of her language. After the first day spent at her side, I was able to follow her stories to some degree. The outdated phrases which I had not understood at first returned so regularly that I soon guessed their meaning. Still, I regularly lost the thread when Agafya’s tales seamlessly jumped from the biographical to the biblical, as if there was no clear boundary between the two. But little by little the fragments of her life story that I got to hear between river bank and forest edge, between potato field and fish trap, began to add up and form a picture.

Her father, Karp Ossipovich Lykov, had been born a good decade before the Revolution, the child of a Siberian family of Old Believers. Agafya’s grandparents, whom she never met, raised their nine children in a tiny settlement called Tishi, located on the shores of the Abakan, about 100 kilometres upstream from Abaza. The village consisted of ten or 12 houses, inhabited by large Old Believer families like the Lykovs, who lived in Tishi in almost complete seclusion from the world.

Young Karp Lykov’s beard was not yet very long when one day a revolutionary planning squad turned up in Tishi. The Bolsheviks took a good look at the village. In the end they pointed at the Old Believers’ fish traps. ‘Very good,’ they said, ‘the state needs fish – from now on, your settlement will be a fishing cooperative.’

The Old Believers did not think too much of that idea. Overnight they gave up their village. Some of them fled into the Altai Mountains. Others, including the newly married Karp Lykov, moved upstream along the Abakan, deeper into the Taiga. They settled down on a tributary called Kair. The Old Believers had hardly built new houses for themselves when the next bunch of uniformed people turned up. This time the Bolsheviks made no effort with the stubborn hermits. Instead of talking about cooperatives, they unceremoniously pointed at the Old Believers’ fishing nets: ‘Hand them over! The state needs nets!’

The Old Believers did not want to give up their nets. A shot was fired. Karp Lykov’s brother collapsed, the bullet had hit him in the stomach. He bled to death while the Bolsheviks packed up the nationalised fishing nets. Before they disappeared, they shouted: ‘Your children belong to the state! Send them to school or we will come to pick them up!’

After that the Old Believers split up a second time. The younger families fled to the Altai Mountains. A few old people, including Karp Lykov’s parents, stayed on the Kair. Karp Lykov himself, who had two small children, did neither the one nor the other. He knew about the ‘godless science’ that was taught in the Bolshevik schools. He also knew the Old Believer settlements in the Altai Mountains, and he did not believe that his children would be any safer there. So he moved in the opposite direction: upstream along the Abakan, even deeper into the Taiga.

When the family separated, Karp’s mother prayed to God: ‘You have taken one son, now take my other children as well, take all nine of them. Do not let them suffer in this world.’

In the years before the war broke out, God took Yevdokim and Stepan, Anastasiya and Alexandra, Feoktista and Fioniya, Anna and Darya. But He did not take Karp Lykov.

A few years later Karp’s wife Akulina gave birth to her fourth child in the Taiga. Agafya was born on the shore of the Yerinat, in the same place where she lives today.

Shortly after her birth the Lykovs, who had not encountered any people for years, ran into two stray border guards by the river bank. The men talked about the war against the Germans, which had not yet ended. Then they asked Karp Lykov his age. Agafya’s fa...

Table of contents

- A Journey into Russia

- Contents

- I. ICE (Kiev)

- The Puzzle

- Russia is not a Country

- Lenin’s Nose

- The Saviour of Chernobyl

- II. BLOOD (Moscow)

- We Fight, We Reconcile

- A Short History of the World

- A Kettle of Water Minus the Kettle

- The Trail of the Icons

- Yevgeny of Chechnya

- The Return of the Wooden Gods

- III. WIND (Saint Petersburg)

- Peter the Seasick

- The Last Heir to the Throne

- A Would-Be Saint

- 24 Centimetres

- Beetles and Communists

- IV. WATER (Siberia)

- Trans-Siberian Chocolate

- Do Bees Have a Five-Year Plan?

- Messiah of the Mosquitoes

- You Shall Know Them by Their Beards

- Where to, Arkashka?

- Blood and Vodka

- V. GRASS (The Steppes)

- Wood People and Grass People

- The Morgue of Yekaterinburg

- The Cossacks’ Last Battle

- A Trunk Full of Icons

- VI. WOOD (Taiga)

- Misha and Masha

- The Secrets of Russian Women

- The Long Walk to Paradise

- Thanks

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Journey into Russia by Jens Mühling, Eugene H. Hayworth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Travel. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.